The death toll from an outbreak of coronavirus in Italy rose in the last 24 hours by 427 to 3,405, overtaking the total number of deaths so far registered in China, officials said on Thursday.

Thursday’s figure represented a slight improvement on the day before, when Italy recorded 475 deaths from COVID-19, while the world has stepped up efforts against the coronavirus pandemic by closing schools, shutting down cities and imposing strict border controls.

Nearly 220,000 people have now been confirmed with the coronavirus globally, of which at least 84,000 have recovered from COVID-19, while more than 8,800 have died, according to data from Johns Hopkins University in the US.

Click here for Friday 20 March updates

20:00 GMT – Potential coronavirus treatment touted by Trump already in shortage -pharmacists

Supply of a malaria treatment that has been tried with some success against the new coronavirus is in short supply as demand surges amid the fast-spreading outbreak, according to independent pharmacies and the American Society of Health-System Pharmacists (ASHP).

The ASHP, which maintains a list of drugs in shortage independent of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s list, plans to add the generic malaria drug hydroxychloroquine to its list of shortages later on Thursday, according to Erin Fox, senior director of drug information at the University of Utah Health, who maintains the shortages list for the ASHP.

The FDA could not be immediately reached for comment, but hydroxychloroquine is not currently on its list of drugs in shortage.

President Donald Trump on Thursday called on US health regulators to expedite potential therapies aimed at treating COVID-19 for which there are no approved treatments or vaccines.

19:55 GMT – US sick leave aid leaves millions of workers in the cold

It’s usually standing room only at O’Duffy’s Pub on St Patrick’s Day, as patrons clad in green pack into the bar to share a drink or two and plenty of food. But this year, owner Jamie Kavanaugh and one of his bartenders sat alone on the holiday that commemorates Ireland’s patron saint. Like restaurants across the country, Kavanaugh’s Kalamazoo, Michigan, bar is now only allowed to serve takeout food as part of social distancing ordinances meant to curb the coronavirus pandemic.

“People are usually celebrating, smiling, toasting one another, sharing hugs and smiles. Instead, the pub is empty,” Kavanaugh told Al Jazeera. “People that came in for takeout didn’t even want to come in the door, and they’re afraid to use the pen to sign.”

Read more here.

19:50 GMT – Amazon shutters NYC warehouse after worker catches coronavirus

Amazon said it was closing a small New York City warehouse temporarily after one of its associates tested positive for the coronavirus, a move that highlights the operational risk it faces as the disease spreads.

The company said it has sent associates home from the delivery station with full pay as it sanitises the facility, its first in the United States known to have a case of the virus.

Read more here.

19:48 GMT – Israelis ordered to stay at home to halt coronavirus spread

Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu tightened a national stay-at-home policy, announcing guidelines aimed at halting the spread of the coronavirus would now be enforced by police under emergency orders.

“Under these orders, you, Israel’s citizens, are required to stay at home. It is no longer a request, it is not a recommendation, it is an obligatory directive that will be enforced by enforcement authorities,” Netanyahu said in a televised address.

The measures stopped short of a total national lockdown: Netanyahu said Israelis would still be allowed to shop for food and medicine, and some workers would be exempted from the restrictions.

Israel’s Health Ministry has reported 573 confirmed cases of coronavirus infection. 47 cases have been reported among Palestinians in the occupied West Bank.

19:40 GMT – US slaps sanctions on UAE-based firms over Iran oil purchases

The United States on Thursday slapped sanctions on five United Arab Emirates-based companies, accusing them of having collectively purchased hundreds of thousands of metric tons of petroleum products from Iran last year.

The move was the latest sign that Washington is showing no signs of backing away from squeezing Iran’s economy, even as the Islamic Republic struggles to battle the coronavirus outbreak.

Read more here.

19:18 GMT – Eight new coronavirus cases reported in Qatar, 10 recoveries

Qatar has announced eight new cases of COVID-19, and the recovery of 10, bringing the number of confirmed cases to 460, the ministry of health said.

The ministry also approved home quarantine as a second option for families arriving from abroad after passing a mandatory medical examination.

Until now 9,460 people have been tested for COVID-19 in Qatar.

19:05 GMT – France reports a huge spike in coronavirus deaths, raising total to 237

French SMUR rescue team wearing protective suits carry a patient at Strasbourg University hospital as France faces an aggressive progression of the coronavirus disease [Christian Hartmann/Reuters]

French health authorities reported 108 new deaths from coronavirus, taking the total to 372 or an increase of almost 41 percent, the toll rising sharply yet again as the country was in its third day of a lockdown aimed at containing the outbreak.

During a press conference, health agency director Jerome Salomon added the number of cases had risen to 10,995, up from 9,134 on Tuesday, which is a rise of 20 percent in 24 hours.

Salomon said 1,122 people were in a serious condition, needing life support, up 20.5 percent compared to Wednesday.

It is estimated France has around 5,000 beds equipped with the necessary gear but these are unevenly spread around the country.

19:00 GMT – Coronavirus cases in Ireland rises to 557 from 366

The total number of confirmed cases of coronavirus in Ireland rose to 557 on Thursday from 366 a day earlier, the highest daily increase so far, the health department said.

“In broad terms, the total number of cases is not out of line with what we have predicted for the course of the week,” Ireland’s chief medical officer, Tony Holohan, told a news conference.

18:48 GMT – Number of coronavirus deaths in UK rises to 144

The number of people in the United Kingdom who have died after contracting the coronavirus rose to 144, up 40 percent in a day, the health ministry said.

The number of positive cases increased by 643, or 25 percent, to 3,269.

18:00 GMT – UK Queen urges Britons to ‘work as one’ to beat virus

Queen Elizabeth II has moved to Windsor Castle outside of London due to coronavirus [File: Anadolu Agency]

Queen Elizabeth II said that “we all have a vitally important part to play” in battling the coronavirus crisis, in her first official message on the outbreak.

The Queen, who has been moved to Windsor Castle outside of London due to the virus, called on Britons to draw on their past as they enter “a period of great concern and uncertainty.”

“I am reminded that our nation’s history has been forged by people and communities coming together to work as one, concentrating our combined efforts with a focus on the common goal,” she said in a statement issued by Buckingham Palace.

“I am certain we are up to that challenge. You can be assured that my family and I stand ready to play our part,” she added.

17:40 GMT – 9,800 people in quarantine in Turkey

A man looks out from a dormitory where he is placed in quarantine in response to the spreading of COVID-19 after returning from abroad, in Istanbul [Umit Bektas/Reuters]

Due to the COVID-19 outbreak, 9,800 people are currently under quarantine in Turkey, the interior minister said.

Speaking to the reporters in the parliament, Suleyman Soylu said the number of quarantined people, including pilgrims who returned from their Islamic pilgrimage of Umrah in Saudi Arabia, is 9,800 across the country.

Soylu also said 64 of 242 suspects allegedly posting fake and provocative coronavirus posts on social media were detained.

Turkey has so far reported 191 cases, with three deaths.

17:30 GMT – US CDC reports 10,491 coronavirus cases, 150 deaths

The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has reported 10,491 cases of coronavirus, an increase of 3,404 cases from its previous count, and said the death toll had risen by 53 to 150.

Coronavirus cases have been reported in all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

The CDC figures do not necessarily reflect cases reported by individual states.

17:25 GMT – Italy overtakes China’s death toll

Italy’s death toll from an outbreak of coronavirus rose in the last 24 hours by 427 to 3,405, overtaking the total number of deaths so far registered in China, officials said.

Thursday’s figure represented a slight improvement on the day before, when Italy recorded 475 deaths.

Some 3,245 people have died in China since the virus first emerged there late last year. Italy’s outbreak came to light in the north of the country on February 21.

The total number of cases in Italy rose to 41,035 from a previous 35,713, up 14.9 percent, a faster rate of growth than seen over the last three days, the Civil Protection Agency said.

17:20 GMT – Trump presses FDA to fast-track potential coronavirus drugs

President Donald Trump called on US health regulators to expedite potential therapies aimed at treating COVID-19 amid the fast-spreading coronavirus outbreak, saying it could lead to a breakthrough while a vaccine is still under development.

Trump, speaking at a news conference, pointed to efforts on Gilead Sciences Inc’s experimental antiviral drug Remdesivir and the generic antimalarial drug hydroxychloroquine, saying he had called on the US Food and Drug Administration to streamline its regulatory approval process.

“We have to remove every barrier,” Trump said.

Trials on potential coronavirus therapies are already in the works and it was unclear how Trump’s call for faster experimental testing process could further expedite an effective treatment.

17:05 GMT – Egypt shuts all airports, suspends flights

Egypt has shut down its airports and air travel until March 31 to contain the outbreak of the coronavirus.

The new measures will heavily impact the country’s economy and tourism sectors, with some 138,000 jobs immediately at risk and a loss of $1bn in airline revenues, according to IATA.

No tourists were in sight near Giza’s pyramids, Egypt’s iconic landmarks, and coffee shops and restaurants were shuttered in Cairo, a city of over 20 million.

Egypt, which has reported nearly 210 cases and six deaths from the virus, has suspended flights, closed schools, and is quarantining more than 300 families in a Nile Delta village, and imposed a lockdown in the Red Sea resort town of Hurghada.

16:55 GMT – Sharp increase in Moscow pneumonia cases

A reported sharp increase in pneumonia cases in the Russian capital and contradictory information around the issue is fuelling fears about the accuracy of official coronavirus data as it remains much lower than many European countries.

Russia, which has a population of 144 million, has reported just 199 coronavirus cases and some doctors have questioned how far the official data reflects reality, given what they say is the patchy nature and quality of testing.

A spike in pneumonia cases in Moscow, Russia’s biggest transport hub and a city with a population of about 13 million, has further raised doubts.

“I have a feeling they [the authorities] are lying to us,” said Anastasia Vasilyeva, head of Russia’s Doctor’s Alliance trade union.

The government, however, says its statistics are accurate and President Vladimir Putin has complained that Russia is being targeted by fake news to sow panic.

16:42 GMT – South Africa to erect 40km fence on Zimbabwe border

South African authorities announced they would erect a fence along its border with Zimbabwe to prevent undocumented immigrants from entering and spreading the coronavirus.

President Ramaphosa has already ordered 35 out of 53 land entry points closed.

“This measure will … not be effective if the fences at the border are not secure, which in many places, they are not,” Public Works Minister Patricia de Lille said in a statement.

South Africa has long sought to reduce irregular migration from Zimbabwe, which it sees as a threat to local jobs in a country with unemployment of around 30 percent.

15:45 GMT – ‘Quarantine shaming’: US navigates radical new social norms

“Quarantine shaming” – calling out those not abiding by social distancing rules – is part of a new and startling reality for Americans who must navigate a world of rapidly evolving social norms in the age of COVID-19.

As schools close and shelter-in-place orders sweep across the US, the divide between those who are stringently practicing self-isolation and those still trying to go about some semblance of normal life has never been clearer.

Complicating matters, what was socially acceptable even 48 hours ago may now be taboo, as government officials race to contain the virus with ever-expanding circles of social isolation.

“The time matrix seems to be shifting. I’ve never known several days to go by so slowly and watching the collective conscience move more and more in one direction day by day,” said Paula Flakser, who lost her bartending job when California’s Mammoth Mountain ski resort closed this week.

15:30 GMT – Africa sees ‘extremely rapid evolution’ of the pandemic, UN says

More African countries closed their borders on Thursday as the coronavirus’s local spread threatened to turn the continent of 1.3 billion people into an alarming new front for the pandemic.

“About 10 days ago we had about five countries” with the virus, WHO’s Africa chief Dr Matshidiso Moeti told reporters. Now 34 of Africa’s 54 countries have cases, with the total close to 650. It is an “extremely rapid evolution”, she said.

15:05 GMT – Iran’s death toll from coronavirus rises to 1,284

Members of firefighters wear protective face masks amid fear of COVID-19, as they disinfect the streets before the Iranian New Year Nowruz in Tehran [Ali Khara/ WANA via Reuters]

The new coronavirus is killing one person every 10 minutes in Iran, a health ministry spokesman said, as the death toll in the Middle East’s worst-affected country climbed to 1,284.

“Based on our information, every 10 minutes one person dies from the coronavirus and some 50 people become infected with the virus every hour in Iran,” Kianush Jahanpur tweeted.

Iran’s Deputy Health Minister Alireza Raisi said the total number of infections had reached 18,407 in the Islamic republic.

The virus has also dampened Iran’s celebrations for the Nowruz New Year that begins on Friday. Authorities have urged people to stay home and avoid traveling during the holiday period to help contain the spread.

14:45 GMT – English Premier League further postponed until April 30

A view inside the Premier League headquarters in London [Justin Setterfield/Getty Images]

The FA, Premier League and EFL announced that the suspension of English football has been extended until at least April 30 amid the coronavirus pandemic. The statement also revealed that the current season will be “extended indefinitely”.

“The progress of Covid-19 remains unclear and we can reassure everyone the health and welfare of players, staff and supporters are our priority,” a statement said.

The FA’s rules and regulations state the season shall terminate no later than the June 1 but it was agreed this can be “extended indefinitely” for the 2019-20 campaign.

14:30 GMT – Wall Street and Main Street on watch to see if Trump gains erased

US stocks extended their losses on Thursday, opening lower on the heels of Wednesday’s session that saw the Dow Jones Industrial Average close below 20,000 for the first time since February 2017 – a hair’s breadth from erasing all of its gains since President Donald Trump took office.

Trump has touted the performance of the Dow throughout his presidency, taking credit for the economy’s continued expansion – now in its 11th year – and for the stock market marking new record highs. But what went up, coronavirus is now bringing down – with a vengeance.

Read more here.

14:25 GMT – France says no hugging loved ones

A couple sit in a restaurant in Nice, France even as the country closed almost all non-indispensable locations, notably cafes, restaurants, cinemas, nightclubs and shops due to concerns over the coronavirus disease [File: Eric Gaillard/Reuters]

French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe pleaded for people to keep their distance from one another to avoid spreading the virus, even as the crisis pushed them to seek comfort.

“When you love someone, you should avoid taking them in your arms,” he said in parliament. “It’s counterintuitive, and it’s painful; the psychological consequences, the way we are living, are very disturbing – but it’s what we must do.”

14:15 GMT – Italy’s death toll nears China’s

Italy, a country of 60 million, registered 2,978 deaths on Wednesday after 475 people died in a day. Given that Italy has been averaging more than 350 deaths a day since March 15, it is likely to overtake China’s 3,249 dead – in a country of 1.4 billion – when Thursday’s figures are released.

The United Nations and Italian health authorities have cited a variety of reasons for Italy’s high toll, key among them its large elderly population that is particularly susceptible to developing serious complications from the virus. Italy has the world’s second-oldest population after Japan and the vast majority of Italy’s dead – 87 percent – were over age 70.

Jonas Schmidt-Chanasit, a virologist at Germany’s Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, said Italy’s high death rate could be explained in part by the almost total collapse of the health system in some parts.

“And then people die who wouldn’t have died with timely intervention,” he said. “That’s what happens when the health system collapses.”

14:00 GMT – Thousands rush to leave the Philippines amid month-long lockdown

Passengers wearing masks stand by with their luggage outside the Ninoy Aquino International Airport in Paranaque, Metro Manila, amid fears of COVID-19 spreading in the Philippines [Eloisa Lopez/Reuters]

Thousands of people have rushed to the main international airport of the Philippines in a bid to get out of the country amid a month-long lockdown on the main island designed to stop the spread of the new coronavirus.

Foreigners and Filipinos crowded Ninoy Aquino International Airport in Manila to try to get on a flight out of the country, where 217 cases of COVID-19 have been confirmed, with 17 deaths.

The exodus came as Foreign Secretary Teodoro Locsin announced the Philippines was temporarily suspending the issuance of visas to all foreigners.

“Starting today, all our embassies and consulates will temporarily suspend visa issuance to all foreign nationals as well as the visa-free entry privileges of all foreign nationals,” he said.

13:45 GMT – Panic buying forces South African supermarkets to ration food

A supermarket’s vegetable racks are empty as people stock up on food after the government announced measures to curb coronavirus infections in Hillcrest, South Africa [Rogan Ward/Reuters]

South Africa’s biggest supermarket Shoprite said it will limit the purchase of some food products and medicines as frantic shoppers emptied shelves to prepare for possible isolation during the coronavirus outbreak.

As the spread of the infection triggers panic buying across the world, South African retailers are saying they are working with their suppliers to ensure a consistent supply of products like meat and canned food, and medicine.

To ensure more people have access to everyday essentials, Shoprite said it is now rationing the sale of toilet paper, tissues, wipes, liquid soap, hand sanitizer as well as some tinned foods, cereals, antiseptic disinfectant liquids, medicines and vitamins.

13:32 GMT – South Asia snapshot: How bad is the coronavirus outbreak?

South Asian countries are beginning to see their first deaths from the coronavirus outbreak, with COVID19 claiming at least six lives across the region amid a spike in cases in Pakistan and elsewhere.

The outbreak does not appear to have reached the widespread secondary contact stage seen in Europe and the US – and earlier in China and South Korea – yet, but cases are continuing to rise as governments across the region scramble to enforce social distancing guidelines.

Read more here.

13:28 GMT – Dutch PM tells citizens there is enough toilet paper for 10 years

The prime minister of the Netherlands told citizens on Thursday there is no shortage of toilet paper.

“Yes, I have enough,” Mark Rutte told a shopper in an informal exchange while visiting a supermarket to show support for workers. “They have it [on shelves] again.”

“But there’s enough in the whole country for the coming 10 years,” he said. “We can all poop for 10 years.”

Dutch supermarkets’ shelves have mostly refilled following a stockpiling episode last week.

12:40 GMT – Experts say Somalia under great coronavirus risk

Medical experts and analysts warn that the coronavirus pandemic could kill more people in Somalia than anywhere else if preventive measures are not put in place urgently.

The East African country confirmed its first case of COVID-19 on Monday in a student who returned from China.

Read more here.

12:33 GMT – EU’s top Brexit negotiator Barnier tests positive

The European Union’s chief negotiator for Brexit, Michel Barnier, said he had tested positive for COVID-19, the disease caused by the novel coronavirus.

“I would like to inform you that I have tested positive for COVID-19. I am doing well and in good spirits. I am following all the necessary instructions, as is my team,” he said on Twitter.

I would like to inform you that I have tested positive for #COVID19. I am doing well and in good spirits. I am following all the necessary instructions, as is my team.

For all those affected already, and for all those currently in isolation, we will get through this together.

— Michel Barnier (@MichelBarnier) March 19, 2020

12:10 GMT – India bars international commercial passenger flights

India’s government said it will ban all scheduled international commercial passenger flights from landing in the country from March 22 for one week to contain the spread of the coronavirus.

India has already suspended visas for the vast majority of foreigners seeking to enter the country.

11:52 GMT – Spain’s coronavirus death toll climbs by over 200 in a day

Spain’s health ministry said the death toll from the coronavirus epidemic soared by 209 to 767 fatalities from the previous day.

A total of 17,147 people have contracted the disease in the country, a roughly 25 percent increase over the previous day, according to the health ministry, with the figure expected to rise further in the coming days as testing for COVID-19 becomes more readily available.

There were 13,716 cases in Spain on Wednesday.

11:40 GMT – Africa told to prepare for worst

From imposing travel bans to prohibiting mass gatherings and shutting down schools, governments across Africa are increasingly adopting sweeping measures in a bid to curb the spread of the new coronavirus.

However, experts warn that the number of cases in the continent was likely higher and urge African countries to “wake up” to the increasing threat.

Read more here.

Experts say African countries should prepare for the worst [Feisal Omar/Reuters]

11:26 GMT – the Netherlands tests blood samples for unseen coronavirus spread

Dutch health authorities have begun a major project testing blood donation samples to see how many people in the Netherlands may have already had the new coronavirus.

The project is being carried out on 10,000 blood donation samples a week by blood bank Sanquin, in cooperation with the country’s National Institute for Health (RIVM).

“It’s possible that you had coronavirus without being sick,” Sanquin spokesman Merlijn van Hasselt told national broadcaster NOS. “If we test for antibodies, we can see whether you’ve already had it … and over time get a picture of how that’s evolving.”

So far there have been 2,051 cases in the Netherlands of COVID-19 and 58 deaths [Jean-Pierre Geusens/ANP/AFP]

11:20 GMT – Coronavirus coping mechanisms from around the world

People around the world are trying to cope with the coronavirus pandemic as it rapidly spreads.

Here is a collection of wonderful and sometimes odd coping mechanisms from around the globe.

10:58 GMT – South Korea pledges $39bn funding for small businesses

South Korean President Moon Jae-in pledged 50 trillion won ($39bn) in emergency financing for small businesses and other stimulus measures to prop up the coronavirus-hit economy.

The package is the latest in a string of steps the South Korean government has taken to curb pressure on Asia’s fourth-largest economy, including an interest rate cut, an extra 11.7 trillion won ($9.12bn) budget and more dollar supplies.

The government will issue loan guarantees for struggling small businesses with less than 100 million won ($78,000) in annual revenue to ensure they can easily and cheaply get access to credit, Moon said.

09:57 GMT – Sri Lanka defers elections

Sri Lanka will not conduct the parliamentary elections as scheduled on April 25 due to the coronavirus outbreak, Mahinda Deshapriya, the chairman of the country’s election commission, said.

The government earlier this week banned all incoming flights for two weeks and imposed a curfew in some areas to rein in the spread of the disease.

There have been over 50 confirmed cases of coronavirus in Sri Lanka so far.

09:55 GMT -Trump defends calling coronavirus the ‘Chinese virus’

US President Donald Trump has been criticised for repeatedly referring to the coronavirus as the “Chinese Virus”, with critics saying he is “fuelling bigotry” and putting Asian-American communities at risk.

However, Trump defends his labelling of the pandemic. Here is how:

09:43 GMT – Thailand reports 60 new cases

Thailand recorded 60 new coronavirus cases in the biggest daily jump in the number of cases so far to take its total infections to 272, a health official said.

The new cases fall into two groups, the first consists of 43 cases linked to earlier cases, while the second group involves 17 new patients including arrivals from countries such as Italy, Malaysia, Japan, Iran and Taiwan, Suwannachai Wattanayingcharoenchai, director-general of Department of Disease Control at the Ministry of Health, told a news conference.

Thailand has recorded one death since the outbreak, with 42 patients having recovered and gone home and 229 still being treated in hospital.

09:22 GMT – Israel: Palestinian prisoners contracted coronavirus

Israeli authorities and Palestinian local media said that four Palestinian prisoners had coronavirus infection.

The cases were contracted in Megiddo prison in Israel, reports said.

09:22 GMT – Malaysia reports 110 new cases

Malaysia reported 110 new coronavirus cases, with the total number of cases increasing to 900.

Most of the new cases were linked to a religious gathering at a mosque attended by 16,000 people, the health ministry said.

Security officers check the temperature of visitors inside a mall during the first day of a movement control order issued by the Malaysia government [Fazry Ismail/EPA]

09:15 GMT – A journalist’s story of making her way home before lockdown

Manila-based journalist Ana Santos was attending a training program in El Salvador when the coronavirus pandemic started around the world.

The program was canceled and she had to return to her country, the Philippines, immediately.

She had a little more than 48 hours to take a nearly 24-hour-long flight to Manila before the whole country was sealed off.

Here, she describes the hurdles she went through trying to get home as the pandemic accelerated.

08:53 GMT – All you need to know about coronavirus

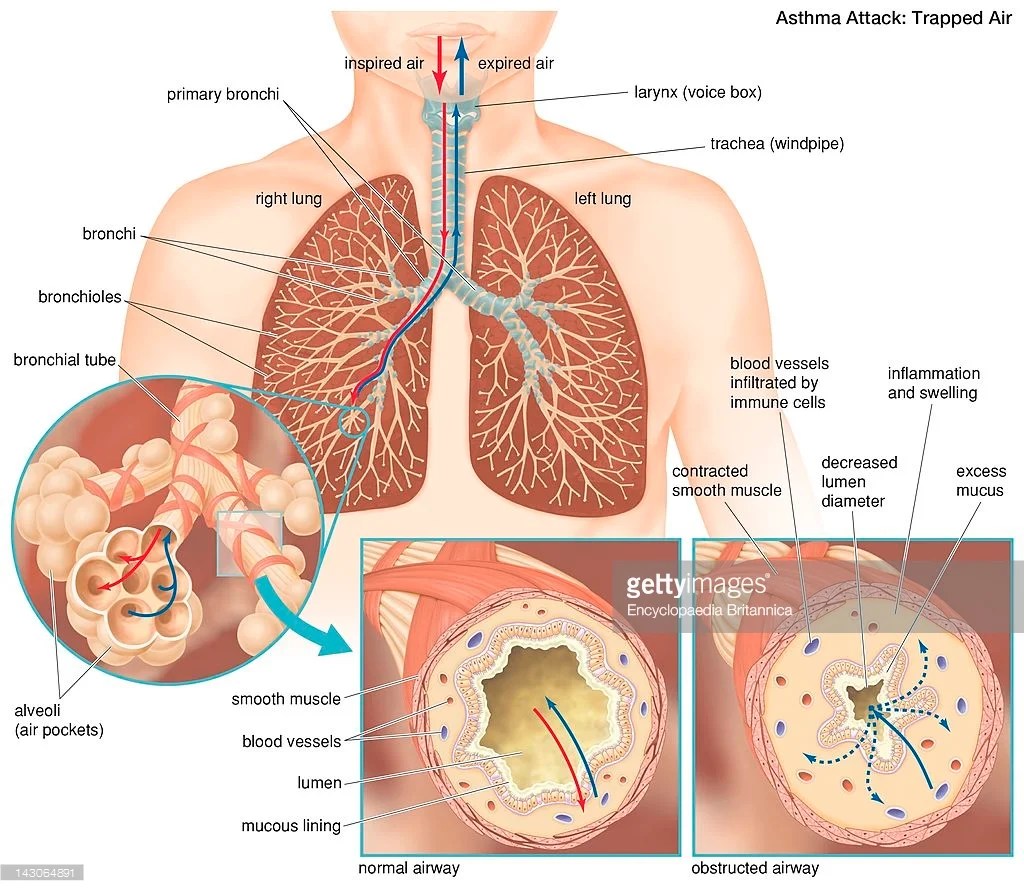

According to the WHO, coronaviruses are a family of viruses that cause illnesses ranging from the common cold to more severe diseases such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and the Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS).

WHO says signs of infection include fever, cough, shortness of breath and breathing difficulties.

Here is all you need to know about the coronavirus.

08:40 GMT – PM Conte: Italy to prolong anti-coronavirus lockdown

Italy will remain under lockdown beyond previous deadlines due to expire later this month and in early April, Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte said.

In comments to the Corriere della Sera newspaper, Conte said measures taken to close schools, universities and to impose severe restrictions on movement would have to be prolonged.

Under current measures, Italy’s 60 million people are only allowed to travel for work, medical reasons or emergencies under an order that runs until April 3, while most shops, except those selling food and pharmacies, are supposed to remain closed until March 25.

07:10 GMT – Russia reports first coronavirus death

Russia said a 79-year-old woman with underlying health issues, who tested positive for the new coronavirus, had died from pneumonia, the country’s first confirmed death resulting from the virus.

Russia has so far reported 147 cases of the coronavirus.

Read more here.

06:35 GMT – Up to 20,000 UK military personnel to go on standby

Up to 20,000 British military service personnel will be put on standby to help tackle the coronavirus outbreak, the defence ministry said.

The number represented a doubling of service personnel who are on standby.

06:15 GMT – Medical volunteers spread coronavirus awareness in Syria

As the coronavirus takes a firmer hold across the Middle East, there is growing concern that war-torn Syria might face a major outbreak.

As concerns over a possible catastrophic prospect grow, a group of medical volunteers in northern Syria teach displaced Syrians how to help prevent catching coronavirus.

06:00 GMT – German minister tested negative for coronavirus

German Finance Minister Olaf Scholz said that his test for the coronavirus came back negative.

Scholz added in a tweet that his cold was subsiding slowly and that he would join discussions at Chancellor Angela Merkel’s office on Thursday.

“The #corona crisis is challenging us all – together we can weather it. Our country can do it,” Scholz added. Die Stimme ist noch mitgenommen, die Erkältung geht etwas zurück und der Test war negativ. Vielen Dank für die vielen guten Wünsche. Heute kein Homeoffice, sondern Beratungen im Kanzleramt. Die #Corona-Krise fordert und alle – gemeinsam stehen wir das durch. Unser Land kann das.

— Olaf Scholz (@OlafScholz) March 19, 2020

05:45 GMT – Lufthansa: Airlines might not survive without state aid

Lufthansa said that the airline industry may not survive without state aid if the coronavirus epidemic lasts for a long time.

The German airline group has slashed capacity, proposed short-time working and suspended its dividend, saying it was impossible to forecast the impact of coronavirus on profitability.

“The spread of the coronavirus has placed the entire global economy and our company as well in an unprecedented state of emergency,” CEO Carsten Spohr said in a statement.

“At present, no one can foresee the consequences.”

04:55 GMT – India’s PM to address nation

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi will make a national address on the coronavirus at 8pm (14:30 GMT), he announced on his official Twitter account.

04:50 GMT – World Bank increases virus response package to $14bn

The World Bank has increased its support package for businesses and economies struggling with the impact of the coronavirus.

04:10 GMT – Hokkaido ending state of emergency

Japanese public broadcaster NHK is reporting that an expert panel guiding Japan’s coronavirus response may advise a relaxation of controls in regions that have not seen outbreaks, as the northern island of Hokkaido ends its state of emergency.

The infectious disease experts are due to meet later on Thursday.

Japan, which is due to host the Olympics in July, has insisted it will press ahead with the games even though the pandemic has brought the sports world almost to a standstill.

Japan’s northern island of Hokkaido is lifting a state of emergency declared over the coronavirus [File: Issei Kato/Reuters]

Hokkaido had 154 infections as of Wednesday. Among Japan’s 47 prefectures, 22 have had fewer than 5 coronavirus cases, according to health ministry data.

04:00 GMT – WHO responds on ibuprofen concerns

The WHO has said it is discussing concerns about the use of ibuprofen to treat fever in patients with COVID-19 and is not aware of any negative effects.

It is not recommending against its use.

Q: Could #ibuprofen worsen disease for people with #COVID19?

A: Based on currently available information, WHO does not recommend against the use of of ibuprofen. pic.twitter.com/n39DFt2amF

— World Health Organization (WHO) (@WHO) March 18, 2020

03:55 GMT – Indonesia must ramp up testing – Joko Widodo

Indonesia’s President Joko Widodo says the Southeast Asian nation needs to immediately widen its testing for coronavirus after the country reported 55 new cases on Wednesday.

“I ask that the number of testing kits and the number of test centers are increased and we get more hospitals involved,” Widodo said.

Indonesia has recorded a total of 227 cases so far.

02:30 GMT – Government steps in to call off mass Muslim event in Indonesia

Indonesian authorities have succeeded in convincing a group of Muslim pilgrims to call off a mass rally amid fears it could fuel the spread of the coronavirus.

Officials have spent days trying to get Ijtima Asia, part of the global Tablighi Jama’at movement, to stop the event with 8,500 people already gathering near Makassar in eastern Indonesia.

A similar event in Malaysia which attracted more than 16,000 people led to a surge in cases, not only in Malaysia but also in other Southeast Asian countries.

02:20 GMT – Qantas to halt all international flights from late March

Two-thirds of staff at Australian airline Qantas have been told to go home, with the airline stopping all international flights from the end of March until at least the end of May.

“This is a terrible day that we have to make these decisions on the survival of the national carrier,” the airline’s chief executive Alan Joyce told reporters. “I never thought as a CEO I would have to stand down two-thirds of our people.”

Some domestic flights will continue.

02:10 GMT – New Zealand tells citizens ‘Do not travel’

New Zealanders have been told not to travel given the heightened risk of contracting the coronavirus overseas.

“We are raising our travel alert to the highest level: do not travel,” Foreign Minister Winston Peters said in a statement. “This is the first time, the New Zealand government has advised New Zealanders against traveling anywhere overseas. That reflects the seriousness of the situation we are facing with COVID-19.”

He also urged New Zealanders already overseas to return home.

02:05 GMT – South Korea reports jump in cases after four days of slowing infections

Latest data from South Korea shows a jump in new coronavirus cases with a new outbreak emerging n a nursing home in the hardest-hit city of Daegu.

The Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported 152 new cases, taking the national tally to 8,565.

The country had recorded fewer than 100 new infections for four days in a row until Wednesday.

Among the new cases, 97 are from Daegu, where the KCDC said at least 74 patients at a nursing home tested positive for the virus this week.

The KCDC did not specify how many of the new cases were linked to the nursing home directly.

The fresh outbreak has prompted Daegu officials to launch extensive checks on all other nursing homes.

01:45 GMT – China reports only imported cases, mostly in Beijing

China’s new cases of coronavirus underscore how the nature of the outbreak has shifted.

The National Health Commission says while there were no domestic cases reported on Wednesday, there were 34 confirmed cases among people returning from overseas. That compares with 13 the day before.

Of the 34 imported infections, 21 were in Beijing.

That brings the total number of confirmed cases in mainland China so far to 80,928.

The death toll rose by eight to 3,245 as of the end of Wednesday.

01:30 GMT – Wuhan and Hubei report no new cases of coronavirus for first time

China’s central city of Wuhan and its surrounding province of Hubei have reported no new cases of coronavirus for the first time.

COVID-19 is thought to have originated in a now-closed seafood market that also sold wildlife late last year.

NO new infections of the novel #coronavirus were reported on Wednesday in #Wuhan, marking a notable first in the city’s months-long battle with the virus. pic.twitter.com/vJ33KQviV9

— Global Times (@globaltimesnews) March 19, 2020

00:30 GMT – US and Canada close border to all but essential traffic

The US and Canada have closed their border to non-essential traffic.

The US and Canada have closed their border to all but essential traffic [Rebecca Cook/Reuters]

00:20 GMT – Trump signs coronavirus response bill

The White House says US President Donald Trump has signed the coronavirus response bill that will allow for free testing and paid sick leave for those working in companies with below 500 employees.

That excludes giant firms like Amazon, McDonald’s and Walmart.

00:05 GMT – Hong Kong introduces compulsory quarantine for all overseas arrivals

Hong Kong has tightened rules for people arriving from overseas.

The territory’s reported a rising number of imported cases and all arrivals will now be required to spend 14 days in quarantine on their arrival in Hong Kong.

The authorities are also urging the city’s residents not to travel.

00:00 GMT – UK to close schools from Friday

The United Kingdom is to close all schools from Friday and cancel national exams, as it ramps up efforts to curb the spread of the coronavirus.

Education Secretary Gavin Williamson told parliament that the situation had become increasingly challenging.

“The spike of the virus is increasing at a faster pace than anticipated,” he said.

In London, which has reported nearly 1,000 cases of the coronavirus, the underground service’s night network – a more limited service – will also be closed down.

I’mKate Mayberryin Kuala Lumpur with Al Jazeera’s continuing coverage of the unfolding coronavirus pandemic.

For all the updates from yesterday (March 18), please click here.

Antibiotic Grouping By Mechanism

Antibiotic Grouping By Mechanism