Facial Paralysis is an idiopathic, acute, unilateral paresis or paralysis of the face in a pattern consistent with peripheral facial nerve dysfunction, and may be partial or complete, occurring with equal frequency on the right and left sides of the face. There is evidence that Bell’s palsy is caused by herpes viruses. Additional symptoms of Bell’s palsy may include mild pain in or behind the ear, oropharyngeal or facial numbness, impaired tolerance to ordinary levels of noise, and disturbed taste on the anterior part of the tongue. Severe pain is more suggestive of herpes zoster virus infection (shingles) and possible progression to a Ramsay Hunt syndrome, but another cause should be carefully excluded. Up to 30% of people with an acute peripheral facial palsy will not have Bell’s palsy; other causes may include stroke, tumor, trauma, middle ear disease, and Lyme disease.

Bell’s palsy is an unexplained episode of facial muscle weakness or paralysis that begins suddenly and worsens over three to five days. This condition results from damage to the 7th (facial) cranial nerve, and pain and discomfort usually occur on one side of the face or head.

Bell’s palsy is the most common peripheral paralysis of the seventh cranial nerve with an onset that is rapid and unilateral. The diagnosis is one of exclusion and most often made on physical exam. The facial nerve has both an intracranial, intratemporal, and extratemporal course as its branches. The facial nerve has a motor and parasympathetic function as well as taste to the anterior two-thirds of the tongue. It also controls salivary and lacrimal glands. The motor function of the peripheral facial nerve controls the upper and lower facial muscles. As a result, the diagnosis of Bell’s palsy requires special attention to forehead muscle strength. If forehead strength is preserved, a central cause of weakness should be considered. Although the utility of antivirals has been called into question, treatment is medical with most sources recommending a combination of corticosteroids and antiviral medication.[1][2][3]

www.rxharun.com

The Others Names of Bell’s palsy

- Antoni’s Palsy

- Facial Nerve Palsy

- Facial Paralysis

- Idiopathic Facial Palsy

- Refrigeration Palsy

- Idiopathic peripheral facial palsy; Cranial mononeuropathy – Bell palsy

Causes of Facial Paralysis

Bell’s palsy is an acute form of cranial neuropathy. This means that it involves damage to a single nerve, in this case the seventh cranial, or facial, nerve. This is the nerve that controls the movement of muscles of facial expression. The cause is unknown, but it affects between 1 in 5,000 and 1 in 1,000 people, according to various estimates. In 75% of cases, the palsy is preceded by an upper respiratory infection. The condition has also been associated with head injuries, heart attacks and hypertension.

What other causes of facial weakness are there?

- Ramsay-Hunt Syndrome – Viral infection with the chickenpox virus, herpes zoster, which is shingles of the facial nerve. There is usually significant pain and a rash in the ear. Other cranial nerves may be affected leading to hearing loss balance disturbance an numbness.

- Skull fractures involving the temporal bone – the bone that contains the middle ear. The facial nerve travels through this bone on its way to the facial muscles and so may be damaged usually with significant trauma to the head.

- High neck injuries, particularly a stab wound to the upper neck.

- Tumors anywhere along the course of the facial nerve, which includes the base of the skull, the ear and the parotid gland just in front of the ear. These will usually present with a gradual loss of weakness to distinguish them from Bell’s palsy

- Middle ear disease, especially cholesteatoma.

- Damage to the facial nerve during ear surgery.

- Loss of power in one side of the face can be a symptom of a stroke but there will be other features present, such as loss of power in a limb, which points to the correct diagnosis.

Facial Nerve Palsy in a Review of Medical Literature (1900-1990)

| Birth | Molding

Forceps delivery Dystrophia myotonica Möbius syndrome (facial diplegia associated with other cranial nerve deficits) |

| Trauma | Basal skull fractures

Facial injuries Penetrating injury to middle ear Altitude paralysis (barotrauma) Scuba diving (barotrauma) Lightning |

| Neurologic | Opercular syndrome (cortical lesion in facial motor area)

Millard-Gubler syndrome (abducens palsy with contralateral hemiplegia caused by lesion in base of pons involving corticospinal tract) |

| Infection | External otitis

Otitis media Mastoiditis Chickenpox Herpes zoster cephalicus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome) Encephalitis Poliomyelitis (type 1) Mumps Mononucleosis Leprosy Influenza Coxsackievirus Malaria Syphilis Scleroma Tuberculosis Botulism Acute hemorrhagic conjunctivitis (enterovirus 70) Gnathostomiasis Mucormycosis Lyme disease Cat scratch Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) |

| Metabolic | Diabetes mellitus

Hyperthyroidism Pregnancy Hypertension Acute porphyria Vitamin A deficiency |

| Neoplastic | Benign lesions of parotid

Cholesteatoma Seventh nerve tumor Glomus jugulare tumor Leukemia Meningioma Hemangioblastoma Sarcoma Carcinoma (invading or metastatic) Anomalous sigmoid sinus Carotid artery aneurysm Hemangioma of tympanum Hydradenoma (external canal) Facial nerve tumor (cylindroma) Schwannoma Teratoma Hand-Schüller-Christian disease Fibrous dysplasia Neurofibromatosis II |

| Toxic | Thalidomide (Miehlke syndrome, cranial nerves VI and VII with congenital malformed external ears and deafness)

Ethylene glycol Alcoholism Arsenic intoxication Tetanus Diphtheria Carbon monoxide |

| Iatrogenic | Mandibular block anesthesia

Antitetanus serum Vaccine treatment for rabies Postimmunization Parotid surgery Mastoid surgery Post-tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy Iontophoresis (local anesthesia) Embolization Dental |

| Idiopathic | Familial Bell palsy

Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome (recurrent alternating facial palsy, furrowed tongue, faciolabial edema) Hereditary hypertrophic neuropathy (Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease, Dejerine-Sottas disease) Autoimmune syndrome Amyloidosis Temporal arteritis Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura Periarteritis nodosa Landry-Guillain-Barré syndrome (ascending paralysis) Multiple sclerosis Myasthenia gravis Sarcoidosis (Heerfordt syndrome, uveoparotid fever) Osteopetrosis |

Clinical features of Facial Nerve Palsy

-

upper motor neurone lesion – based on innervation, absence of forehead wrinkling is a reliable way of differentiating Bell’s palsy from an upper motor neuron lesion

-

herpes zoster oticus (Ramsay Hunt syndrome)

-

rarer causes including otitis media, HIV infection, sarcoidosis, autoimmune disorders or tumours of the parotid gland.

Symptoms of Facial Paralysis

Sometimes, you may have a cold shortly before the symptoms of Bell palsy begi.

Symptoms most often start suddenly, but may take 2 to 3 days to show up. They do not become more severe after that.

Many people feel discomfort behind the ear before weakness is noticed. The face feels stiff or pulled to one side, and may look different. Other signs can include:

- Twitching

- Weakness

- Paralysis on one side of the face

- Problems smiling or making facial expressions

- Difficulty closing your eye

- Drooling due to a lack of control over the facial muscles

- Difficulty closing one eye

- Difficulty eating and drinking; food falls out of one side of the mouth

- Drooling due to lack of control over the muscles of the face

- Drooping of the face, such as the eyelid or corner of the mouth

- Problems smiling, grimacing, or making facial expressions

- Twitching or weakness of the muscles in the face

Bell’s palsy symptoms may come on suddenly or develop over a few days. Initial symptoms may include

- Pain behind the ear that is followed by weakness and paralysis of the face

- Ringing sound in the ears

- Slight fever

- Slight hearing impairment

- Slight increase in sensitivity to sound on the affected side.

Symptoms of full-blown Bell’s palsy may include

- Facial weakness or paralysis (look for smooth forehead and problems smiling)—most often on one side

- Numbness just before the weakness starts

- Drooping corner of the mouth

- Drooling

- Decreased tearing

Inability to close an eye, which can lead to

- Dry, red eyes

- Ulcers forming on the eye

- Infection

- Problems with taste

- Sound sensitivity in one ear

- Earache

- Slurred speech

Late symptoms can occur 3-4 months after or second-time onset of Bell’s palsy and can include

- Muscle weakness or paralysis

- Facial Droop

- Impossible or difficult to blink

- Difficulty speaking

- Difficulty eating and drinking

- Nose runs

- Nose is constantly stuffed

- Difficulty breathing out of nostril on the affected side

- Nostril collapse on the affected side

- Forehead wrinkles disappear

- Sensitivity to sound

- Excess or reduced salivation

- Facial swelling

- Drooling

- Diminished or distorted taste

- Pain behind ear

- Long-lasting tightening of the facial muscles

- Tearing from the eye during eating

Diagnosis of Facial Paralysis

The neurologist may recommend certain diagnostic tests, depending on the patient’s symptoms, medical history and physical examination.

Frequently the neurologist will recommend electrodiagnostic testing to measure the electrical activity of muscles and nerves. If necessary, the neurologist may also recommend a nerve biopsy, a spinal tap or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). However, for some patients with longstanding neuropathy, the cause may not be found in spite of extensive tests and examinations.

GRADE Evaluation of interventions for Bell’s palsy.

| Important outcomes | Presence of sequelae, Recovery of motor function, Time to recovery | ||||||||

| Studies (Participants) | Outcome | Comparison | Type of evidence | Quality | Consistency | Directness | Effect size | GRADE | Comment |

| What are the effects of drug treatments for Bell’s palsy in adults and children? | |||||||||

| 10 (1507) | Recovery of motor function | Corticosteroids versus placebo or no specific treatment | 4 | –1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Moderate | Quality point deducted for the inclusion of some single-blinded studies in the meta-analysis |

| at least 3 (at least 901) | Presence of sequelae | Corticosteroids versus placebo or no specific treatment | 4 | –2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Low | Quality points deducted for incomplete reporting of results and the inclusion of some single-blinded studies in the meta-analysis |

| 1 (829) | Time to recovery | Corticosteroids versus placebo or no specific treatment | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | High | |

| 5 (1228) | Recovery of motor function | Antiviral agents versus placebo | 4 | –1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Moderate | Quality point deducted for the inclusion of single-blinded studies in the meta-analysis |

| 2 (at least 99) | Presence of sequelae | Antiviral agents versus placebo | 4 | –2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Low | Quality points deducted for unclear reporting of number of people in analysis and incomplete reporting of results |

| 3 (768) | Recovery of motor function | Antiviral agents versus corticosteroids | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | High | |

| 7 (1987) | Recovery of motor function | Corticosteroids plus antiviral treatment versus placebo/no treatment | 4 | –1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Moderate | Quality point deducted for the inclusion of some single-blinded studies in the meta-analysis |

| 9 (1504) | Recovery of motor function | Corticosteroids plus antiviral treatment versus corticosteroids alone | 4 | –1 | –1 | 0 | 0 | Low | Quality point deducted for the inclusion of open-label studies in the meta-analysis; consistency point deducted for conflicting results depending on analysis undertaken |

| 1 (99) | Presence of sequelae | Corticosteroids plus antiviral treatment versus corticosteroids alone | 4 | –1 | 0 | –1 | 0 | Low | Quality point deducted for sparse data; directness point deducted for small number of events |

| 2 (660) | Recovery of motor function | Corticosteroids plus antiviral treatment versus antiviral treatment alone | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | High | |

| 1 (79) | Recovery of motor function | Hyperbaric oxygen versus corticosteroids | 4 | –2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Low | Quality points deducted for sparse data and incomplete reporting of results |

| 1 (79) | Time to recovery | Hyperbaric oxygen versus corticosteroids | 4 | –2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Low | Quality points deducted for sparse data and incomplete reporting of results |

| What are the effects of physical treatments for Bell’s palsy in adults and children? | |||||||||

| 2 (82) | Recovery of motor function | Facial re-training versus waiting list control | 4 | –2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Low | Quality points deducted for sparse data and incomplete reporting of results |

| 1 (145) | Presence of sequelae | Facial re-training versus waiting list control | 4 | –2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Low | Quality points deducted for sparse data and methodological weaknesses |

| 1 (90) | Time to recovery | Facial re-training versus waiting list control | 4 | –2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Low | Quality points deducted for sparse data and incomplete reporting of results |

Blood tests

Blood tests are commonly employed to check for vitamin deficiencies, toxic elements and evidence of an abnormal immune response.

Depending on your individual situation, your doctor may request certain laboratory tests to identify potentially treatable causes for neuropathy. These include tests for:

- Vitamin B12 and folate levels

- Thyroid, liver and kidney functions

- Vasculitis evaluation

- Oral glucose tolerance test

- Antibodies to nerve components (e.g., anti-MAG antibody)

- Antibodies related to celiac disease

- Lyme disease

- HIV/AIDS

- Hepatitis C and B

- Tear problems > Decreased tear production & Recent cold or influenza

- Hearing test—to see if nerve damage involves the hearing nerve, inner ear, or hearing mechanism

- Balance test—to see if balance nerves are involved

- Lumbar puncture —a test of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) from the lower back; to rule out meningitis, autoimmune disorders, or cancer spreading from a tumor

- Tear test—measures the eye’s ability to produce tears

- CT scan —a type of x-ray that uses a computer to make pictures of structures inside the head to see if there is an infection, tumor, bone fracture, or other problem in the area of the facial nerve

- MRI scan —a test that uses magnetic waves to make pictures of structures inside the head to see if there is an infection, tumor, bone fracture, or other problem in the area of the facial nerve

- Electrodiagnostic test

Differential Diagnosis for Facial Nerve Palsy

| DISEASE | CAUSE | DISTINGUISHING FACTORS |

|---|---|---|

|

Nuclear (peripheral) |

||

|

Lyme disease |

SpirocheteBorrelia burgdorferi |

History of tick exposure, rash, or arthralgias; exposure to areas where Lyme disease is endemic |

|

Otitis media |

Bacterial pathogens |

Gradual onset; ear pain, fever, and conductive hearing loss |

|

Ramsay Hunt syndrome |

Herpes zoster virus |

Pronounced prodrome of pain; vesicular eruption in ear canal or pharynx |

|

Sarcoidosis or Guillain-Barré syndrome |

Autoimmune response |

More often bilateral |

|

Tumor |

Cholesteatoma, parotid gland |

Gradual onset |

|

Supranuclear (central) |

Forehead spared |

|

|

Multiple sclerosis |

Demyelination |

Additional neurologic symptoms |

|

Stroke |

Ischemia, hemorrhage |

Extremities on affected side often involved |

|

Tumor |

Metastases, primary brain |

Gradual onset; mental status changes; history of cancer |

The nerve excitability test – determines the excitation threshold by recording the minimum electrical stimulus required to produce visible muscle contraction. A difference greater than 3.5 mA between affected and unaffected sides is considered to be significant in terms of poorer outcome. Measuring the peak-to-peak amplitude of the evoked compound action potential of the involved side compared to the normal side has prognostic importance. If there is a 90% or greater reduction in the amplitude of the affected side, the prognosis is poor.[4]

Currently the trigeminal blink reflex – is the only test to measure intracranial pathway of the facial nerve and also useful test to study various post paralysis sequelae such as synkinesis and hemifacial spasms. With recovery of facial function the ipsilateral R1 latency becomes less prolonged and the amount of initial prolongation of this response correlates with greater loss of facial motor function.

Gadolinium contrast magnetic resonance (MRI) – study reveals enhancement of internal acoustic meatal segment on the affected side; however, this is a non-specific finding. MRI should not be done routinely and should be the investigation to look for other possible causes for acute facial paralysis especially if there is little or no recovery of function.

Treatment of Facial Paralysis

Often, no treatment is needed. Symptoms often begin to improve right away. But, it may take weeks or even months for the muscles to get stronger.

Your provider may give you lubricating eye drops or eye ointments to keep the surface of the eye moist if you can’t close it completely. You may need to wear an eye patch while you sleep.

Sometimes, medicines may be used, but it isn’t known how much they help. If medicines are used, they are started right away. Common medicines are:

- Corticosteroids, which may reduce swelling around the facial nerve

- Drugs such as valacyclovir to fight the virus that may be causing Bell palsy

Surgery to relieve pressure on the nerve (decompression surgery) has not been shown to benefit most people with Bell palsy.

Your healthcare provider will prescribe other treatment for your condition based on the severity of your symptoms and your health history. Other treatment options include:

- Antiviral medicine, such as acyclovir

- Analgesics or moist heat to relieve pain

- Electrical stimulation

- Relaxation techniques – Relaxing by using techniques such as meditation and yoga may relieve muscle tension and chronic pain.

- Acupuncture – Placing thin needles into a specific point in your skin helps stimulate nerves and muscles, which may offer some relief.

- Biofeedback training – By teaching you to use your thoughts to control your body, you may help gain better control over your facial muscles.

- Botulinum Toxin (Botox) Injections – These injections give you the option to treat the unaffected or the affected side of your face. These injections can help your facial muscles to relax to reduce unwanted muscle movements. They can also reduce muscle activity in the unaffected side of your face to maintain a balance. Botox injections may also help treat tears when eating and to keep you from winking an eye when smiling, eating, or laughing.

- Vitamin therapy – Vitamins B-12, B-6 and zinc may help nerve growth.

- Prednisolone – The rationale for the use of corticosteroids in acute phase of Bell’s palsy is that inflammation and edema of the facial nerve are implicated in causing Bell’s palsy and corticosteroids have a potent anti-inflammatory action which should minimize nerve damage and thereby improve the outcome. Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trials have provided compelling evidence that treatment with prednisolone improves outcome in patients with Bell’s palsy and shortens the time to complete recovery.[Rx–Rx]

- Prednisolone – should be used in all patients with facial palsy of less than 72 h duration who do not have contraindications to steroid therapy. The prednisolone dose used was 60 mg per day for 5 days then reduced by 10 mg per day (for a total treatment time of 10 days)[Rx] and 50 mg per day (in two divided doses) for 10 days.[Rx] The reported adverse rates were low. Treatment with prednisolone is likely to be cost-effective.[Rx]

- Antiviral Agents – The rationale for the use of antiviral agents is the evidence that the inflammation of the facial nerve in Bell’s palsy might be related to the herpes simplex virus (HSV). In an autopsy study latent HSV type-1 has been isolated from the majority of the geniculate ganglia samples.[Rx] HSV-1 genome was detected in 79% of facial nerve endoneurial fluid in patients with Bell’s palsy, but not in the controls.[Rx] However, the benefit of acyclovir or valacyclovir, either as single agents or in combination with prednisolone in Bell’s palsy has not been definitively established.[Rx–Rx,Rx,Rx] Thus with the available evidence acyclovir or valacyclovir should not be routine and treatment with acyclovir is highly unlikely to be considered cost-effective.[Rx]

- Physical Therapy – In Bell’s palsy various physical therapies, such as exercise, biofeedback, laser, electrotherapy, massage and thermotherapy are used to hasten recovery. However, the evidence for the efficacy any of these therapies, is lacking. Cochrane systemic review of the efficacy of physical therapies, electrostimulation, and exercises, on the outcome of Bell’s palsy concluded that there was no significant benefit or harm from any of these physical therapies for Bell’s palsy. There was limited evidence that improvement began earlier in the exercise group.[Rx] Another systematic review examined the effects of facial exercises associated either with mirror or electromyogram biofeedback with respect to complications of delayed recovery in Bell’s palsy and concluded that because of the small number of randomized controlled trials, it was not possible to analyze if the exercises, were effective.[Rx] However, that the possibility that facial exercise reduces time to recover and sequelae need confirming with good quality randomized controlled trials.[Rx]

- Combination therapy – A randomized controlled trial found that at nine months of diagnosis, facial function had recovered in 94.4% of patients who took prednisolone alone, 85.4% of those who took aciclovir alone and 92.7% of those who received both. There were no serious adverse effects in any group. The study concluded that early treatment with prednisolone alone increases the likelihood of complete recovery and there was no additional benefit of treatment with aciclovir alone or combining with prednisolone.7However, a systematic review also found that treatment with prednisolone reduced the chances of incomplete recovery but using an antiviral drug had an additional benefit.14

- Hyperbaric oxygen – may improve time to recovery and the proportion of people who make a full recovery compared with corticosteroids; however, the evidence for this is weak.We don’t know whether facial nerve decompression surgery is beneficial in Bell’s palsy.

- Facial retraining – may improve recovery of facial motor function scores including stiffness and lip mobility, and may reduce the risk of motor synkinesis in Bell’s palsy, but the evidence is too weak to draw conclusions.

- The efficacy of acupuncture – remains unknown because the available studies are of low quality (poor primary study design or inadequate reporting practices).[Rx] There is very tentative evidence for hyperbaric oxygen therapy in severe disease.[Rx]

Physiotherapy

- During the earliest stages of Bells palsy, when muscles are completely flaccid, it is advisable to limit therapy to:

- Moist heat (to ease soreness and reduce swelling)

- Massage (also to ease soreness, plus to provide a degree of motion & stimulation to the muscles and increase circulation)

- Mental exercises (to retain the “memory” of facial motions)

A special form of physiotherapy called facial retraining can also help minimize the asymmetrical appearance of the face that occurs when one side is weakened. Examples of facial retraining exercises can include but are not limited to

- Sniffle. Wrinkle nose. Flare nostrils.

- Curl upper lip up and raise and protrude upper lip.

- Compress lips together. Pucker lips & attempt to whistle.

- Smile without showing teeth; then smile showing teeth.

- Try moving your lips into a small smile slowly. Then gently pucker slowly using equal strength from both sides.

- Draw angle of mouth upward so as to deepen furrow from side of nose to side of mouth.

- Harden (wrinkle) the chin; “stick out” the chin (like a boxer).

- Using your index finger and thumb pull the corners of your lips in toward the center. Slowly and smoothly push out and up into a smile. Continue the movement up to the cheekbone. Use a firm pressure.

- Placing 4 fingertips on the eyebrow rub using a firm stroke up to the hairline. Return downward to the eyebrow. Do the same type of massage in a circular motion on your cheeks and chin, and outward to your ear.

- Try to close the eye slowly and gently, without letting your mouth pull up or your eyebrow move downward.

- Raise eyebrows and hold for 10 -15 seconds (watch out for synkinesis – hold the brow at a point before the corner of your mouth starts to move or your cheek tries to help). Wrinkle forehead.

- Frown and draw eyebrows downward.

- Gently wink with one eye and then the other to the best of your ability.

- Open eyes widely, but without involving your eyebrow. Stop if you see any inappropriate muscle actions.

Medications for Treatment of Facial Paralysis

| MEDICATION | DOSING | RENAL ADJUSTMENT | HEPATIC ADJUSTMENT | ADVERSE REACTIONS | COST* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Acyclovir (Zovirax) |

Adults: 400 mg five times daily for seven days |

Creatinine clearance:

|

Undefined |

Gastrointestinal upset, headache, dizziness, elevated liver enzymes, aplastic anemia (rare) |

$66 to $76 (generic)$132 (brand) |

|

Children older than two years: 80 mg per kg daily divided every six hours for five days, with a maximal dose of 3,200 mg daily |

|||||

|

Valacyclovir (Valtrex) |

Adults and children older than 12 years: 1 g three times daily for seven days |

Creatinine clearance:

|

None |

Gastrointestinal upset, headache, dizziness, elevated liver enzymes, aplastic anemia (rare) |

$208 (brand) |

|

Prednisone or prednisolone |

Adults: 60 mg daily for five days, then 40 mg daily for five days |

None |

Undefined |

Headache, nervousness, edema, elevated blood pressure, elevated glucose |

$3 (generic)$6 (brand) |

|

Children: 2 mg per kg daily for seven to 10 days |

*—Estimated cost to the pharmacist based on average wholesale prices (rounded to the nearest dollar) in Red Book. Montvale, N.J.: Medical Economics Data, 2006. Cost to the patient will be higher, depending on prescription filling fee.

Am I going to recover?

Bell’s palsy develops rapidly, with symptoms ‘peaking’ within 48 hours of their onset in many patients, and maximal by 5 days overall. Patients often mistakenly believe they have had a stroke, because of the facial paralysis. In the majority of cases (60-80%), the condition gradually disappears completely within weeks to months. In some there may be slight residual paralysis that is barely noticeable to others. Unfortunately, some people are left with complications of the condition, which include:

- Obvious residual paralysis (e.g. asymmetrical smile, drooling of liquids, inability to close eye, abnormal blinking, tear pooling)

- Dry eye

- Affected taste

- Distorted nerve functions (e.g. tear production with eating, blinking when opening mouth).

In 7-10% of people, Bell’s palsy will recur.

Hyperacusis (distorted hearing) and associated diseases such as diabetes are associated with a poor outcome. Factors that increase the likelihood of better outcome include:

- Young age

- Incomplete paralysis at outset

- Recovery of taste within 1 week

- Early recovery (within 10-21 days).

- The use of facial massage, neuromuscular retraining (e.g. using a mirror to practise the use of facial muscles), acupressure or acupuncture may help enhance the recovery process.

How can you care for yourself at home?

Facial exercises – As the nerve in your face begins to work again, doing simple exercises—such as tightening and relaxing your facial muscles—may make those muscles stronger and help you recover more quickly. Massaging your forehead, cheeks, and lips with oil or cream may also help.

Eye care – If you can’t blink or close your eye fully, your eye may become dry. A dry eye can lead to sores and serious vision problems. To help protect the eye and keep it moist:

- Use your finger to close and open your eyelid often throughout the day.

- Use eyedrops (“artificial tears”) or ointment. Those that contain methylcellulose are a good choice and don’t require a prescription. You may want to use drops during the day and ointment at night while you sleep. Ask your doctor how often to use the drops.

- Wear an eye patch while you sleep, and wear glasses or goggles the rest of the time.

Mouth care. If you have no feeling and little saliva on one side of your tongue, food may get stuck there, leading to gum disease or tooth decay. Brush and floss your teeth often and well to help prevent these problems. To prevent swallowing problems, eat slowly and chew your food well. Eating soft, smooth foods, such as yogurt, may also help.

Surgery of Bell’s Palsy

- Nerve repair or nerve grafts: Facial nerve regeneration occurs at a rate of one millimeter per day. If a nerve has been cut or removed, direct microscopic repair is the best option.

- Nerve transposition: Often the tongue nerve (hypoglossal nerve) or the other facial nerve can be connected to the existing facial nerve. For example, the patient can then train themselves to move their face by moving their tongue.

- Muscle transposition or sling procedures: The temporalis muscle or masseter muscle (some of the only muscles on the face not supplied by the facial nerve), can be moved down and connected to the corner of the mouth to allow movement of the face.

- Muscle transfers: Free muscles from the leg (gracilis) can be used to provide both muscle bulk

Home Remedies for Facial Paralysis

You can improve your chances of recovering faster by taking medications. It is also important to protect your eye if you cannot close your eyelids. Here are some treatment options for quick recovery:

www .rxharun.com

Eye Protection

You can always damage your eye if your eyelids do not close properly. It may also lead to dryness. Your doctor will give you goggles or an eye pad for protection along with eye drops to keep your eye moist. There is also an option of taping the lower and upper lid together to keep your eye closed while you are sleeping.

2.

rx

Try Heat Compress

Apply soaked warm washcloth on face at least 3 times a day to find some comfort. The heat will help to relax facial muscles and prevent atrophy.

3. Massage with Olive Oil

www.rxharun.com

Regular massage with olive oil can increase blood circulation, which will help to improve your paralysis by stimulating damaged nerve. Start with your lower face. Place your thumb and index finger on each corner of your mouth, then push your lips forward and repeat for about 15 times. Next, massage your forehead and around your eyebrows. After that, move to your cheeks. Remember to apply some pressure to massage in a circular motion. Each part of the face shall be massaged for at least 2-3 minutes.

4. Try Castor Oil

www.rxharun.com

Castor oil helps because it’s effective in dealing with swelling, repairing damaged nerve and strengthening facial muscles. To do that, apply a cotton cloth that has been soaked in heated castor oil on the face for at least 3 times a day. For better result, you can use something such as flannel to retain the heat.

5. Eat Some Celery

www.rxharun.com

The vitamins and minerals in celery are beneficial for nerve health and can help to repair damaged nerve. In addition, celery can also boost your immune system. Eat celery, leaves and stick, raw several times a day.

6.

www.rxharun.com

Have Some Ginger and Turmeric

The anti-inflammatory properties in ginger and turmeric are very effective in relieving Bell’s palsy symptoms. You can either add them to your food while cooking or take their supplements.

7. Take Vitamin Supplements

www.rxharun.com

Vitamins such as vitamin B-12, B-6, and zinc can greatly speed up Bell’s palsy recovery. Vitamin B-12 is helpful for neurological conditions while vitamin B-6 helps nerve growth. Vitamin B-1 also helps with its thiamine in treating never inflammation. However, consult your doctor for proper doses before taking them.

Ayurvedic Treatment for Facial Paralysis

Brahmi Capsules

Brahmi capsules of Planet Ayurveda are packed with pure extract of best quality Brahmi. Brahmi is known as Bacopa monnieri scientifically.

Pack Size: 1 Bottle 60 Capsules

Dosage: 1 capsule twice daily with plain water after meals

Ashwagandha Capsules

Ashwagandha capsules of Planet Ayurveda are packed with pure extract of best quality Ashwagandha. Ashwagandha is Withania somnifera scientifically.

Pack Size: 1 Bottle 60 Capsules

Dosage: 1 capsule twice daily with plain water after meals

Curcumin Capsules

Curcumin capsules of Planet Ayurveda are packed with standardized extract of Curcumin, an active compound of turmeric.

Pack Size: 1 Bottle 60 Capsules

Dosage: 1 capsule twice daily with plain water after meals

Chandraprabha Vati

Chandraprabha Vati is a classical natural formulation, blend of many ingredients which are explained in ayurvedic texts. Some of them are Vacha (Acorus calamus), Mustak (Ciprus rotundus), Pippali (Piper longum), Maricha (Piper nigrum), Haridra (Curcuma longa), Vidanga (Emblia ribes) etc.

Over all Chandraprabha Vati maintains healthy body functions.

Pack Size: 1 Bottle 120 Tablets

Dosage: 2 tablets twice daily with plain water after meals

Nirgundi Oil

Nirgundi oil contains Nirgundi (Vitex nigundo) with other ingredients like Haridra (Curcuma longa), Manjista (Rubia cordifolia), Kalahari (Dichrostachys cinerea).

Pack Size: 1 Bottle 100ml

Dosage: for external use. Apply on affected area once to twice daily and massage gently.

Bell’s Palsy/Facial Paralysis(Homeopathy)

Complications of Facial Paralysis

Due to the complexity of our facial muscles and their function, a number of problems can arise following the prolonged experience of having Bell’s palsy

- Contracture – Shortening of the facial muscles over time may make the affected side of the face appear to be slightly ‘lifted’ in comparison to the unaffected side, and the affected eye may appear smaller than the unaffected eye. The fold between the outer edge of the nostril and the corner of the mouth may seem deeper due to the increased contraction of cheek muscles on that side.

- Crocodile tears – This means that the affected eye waters involuntarily, particularly whilst eating. This is due to faulty ‘re-wiring’ of the nerves during the recovery phase.

- Lagophthalmos – This is an inability to close the affected eye, which if prolonged may result in eye dryness and/or corneal ulceration. (This complication can be assisted/prevented by the use of artificial tears and taping the eye down at night.) In rare cases, the vision may be permanently damaged if care is not taken.

- Synkinesis – This means that when intentionally trying to move one part of the face, another part automatically moves. For example, on smiling the eye on the affected side automatically closes. Similarly, on raising the eyebrows or closing the eyes, involuntary contraction of the cheek or neck muscles occurs. Find out more about synkinesis.

- People with persistent symptoms of Bell’s palsy may experience psychological problems including stress, anxiety, depression and low self-esteem

- altered sense of taste

- facial pain, pain in or behind the ear (in fewer than 50% of cases)

- no tears in one eye

- sensitivity to noise on the affected side

There’s none of the confusion, language difficulty, or crushing headache that’s commonly seen in stroke victims. You may have some trouble talking, but it’s purely muscular, whereas stroke victims have difficulty finding the words they need.

Usually, the symptoms appear at once. Occasionally, they worsen over a few days. Steady, progressive paralysis over several weeks is not a sign of Bell’s palsy.

The most serious complication seen in Bell’s palsy is permanent mild facial paralysis. This is found in a minority of cases. Overall, about 80% to 90% recover completely over weeks to months, and most of the rest improve.

Another complication is increased risk of stroke. Stroke prevention and follow-up is recommended.

Incomplete recovery is more likely in people who

- are over age 55

- feel pain other than ear pain

- have weakness/paralysis on both sides of the face – this occurs in 1% of cases

- show a lack of tears

People who don’t recover completely may be left with one or more of the following symptoms

- abnormal blink

- asymmetrical smile

- buccinator paralysis (food caught in cheek of paralyzed side)

- corneal damage

- drooling of liquids from corner of paralyzed mouth

- dry eye

- excessive perspiration

- frozen muscle in the nostril area

- hyperacusis (perceiving sounds as unusually loud)

- impaired taste

- impaired speech

- synkinesis

Summary of topics and recommendations

| Treatment | Severity | Recommendation | Strength | Confidence in effect estimate |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Corticosteroids | Any severity | We recommend the use of corticosteroids for all patients with Bell palsy. | Strong | Moderate |

| Antivirals | Any severity | We recommend against antiviral treatment alone. | Strong | Moderate |

| Corticosteroids + antivirals | Mild to moderate paresis | We suggest against the addition of antivirals to corticosteroids for patients with mild to moderate severity. | Weak | Moderate |

| Severe to complete paresis | We suggest the combined use of antivirals and corticosteroids in patients with severe to complete paresis. | Weak | Moderate | |

| Exercise physiotherapy | Acute; any severity | We make no recommendation regarding the use of exercise physiotherapy for acute Bell palsy of any severity. | Not applicable | Very low |

| Chronic | We suggest exercise physiotherapy for patients with persistent weakness. | Weak | Very low | |

| Electrostimulation | Acute; any severity | We suggest against the use of electrostimulation. | Weak | Very low |

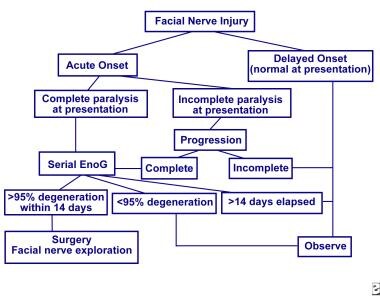

| Surgical decompression | Severe to complete paresis | We suggest against the routine use of surgical decompression. | Weak | Very low |

| Eye-protective measures for incomplete eye closure | Any severity, with incomplete eye closure | We recommend the routine use of eye-protective measures for patients with incomplete eye closure. | Strong | Very low |

| Referral to specialist | Progressive cases | We recommend referral to a specialist for patients with no improvement or progressive weakness. | Strong | Very low |

| Work-up for neoplasm | Progressive cases | We recommend imaging to rule out neoplasms or alternative diagnoses for patients with no improvement or progressive weakness. | Strong | Very |

References