How do you diagnose a deltoid strain?/Deltoid Pain is the large muscle on the shoulder and has three parts the anterior, posterior and the middle. The muscle performs the role of lifting the arm up sideways. The front part helps to lift the arm up forward, which is called shoulder flexion. The back part helps to lift the arm up backward, which is called shoulder extension.

Anatomy of Deltoid Pain

Each head of the deDeltoid Muscle Strainltoid has slightly different insertion points, allowing for more control and a full range of motion at the shoulder joint. The anterior head of the deltoid works closely with a pectoralis major, which allows for full stabilization near its more superior insertion on the clavicle.

- The anterior deltoid – rotates the shoulder joint medially by drawing the arm inward. This flexion and medial rotation allow the arm to move forward, sometimes referred to as forwarding flexion. This action can be seen in a variety of functional tasks and is quite integral to the upper extremity movement. The forward-flexed motion moves the arm toward the insertion point of the anterior deltoid at the clavicle.

- The lateral deltoid – rotates the shoulder joint laterally moving the arm outward, referred to as abduction. This is important while walking, reaching, and completing many other tasks in a lateral plane. This abduction moves the shoulder joint downward to accommodate the movement of the entire arm outward. The contraction of the lateral deltoid pushes the arm toward the insertion point of the lateral deltoid, which is on the proximal humerus.

- The posterior deltoid rotates the joint laterally which moves the arm backward and outward. This moves the entire arm toward the spine, which is where this head of the deltoid inserts. This motion is seen often when dressing, reaching backward, or throwing, among other functional tasks.

Anterior Division

- Origin – anterior border of the lateral 1/3 of the clavicle;

- insertion – deltoid tuberosity of the humerus;

- Action – abduction, horizontal flexion and medial rotation of humerus at shoulder;

- Nerve supply – axillary, C5, C6 ;

- Synergists – medial and posterior deltoid divisions, supraspinatus and pectoralis major clavicular division;

Deltoid: Medial Division

- Origin – the superior surface of the acromion process;

- Insertion – deltoid tuberosity of humerus;

- Action – the abduction of the humerus at the shoulder

- Nerve supply – axillary, C5, C6;

- Synergists – anterior and posterior deltoid divisions, supraspinatus;

Deltoid: Posterior Division

- Origin – inferior margin of the spine of scapula;

- Insertion – deltoid tuberosity of humerus;

- Action – abduction, horizontal extension & lateral rotation of humerus at shoulder;

- Nerve supply – axillary, C5, C6;

- Synergists – anterior and medial divisions of the deltoid, supraspinatus;

Insertion

- From this extensive origin the fibers converge toward their insertion on the deltoid tuberosity on the middle of the lateral aspect of the shaft of the humerus; the middle fibers passing vertically, the anterior obliquely backward and laterally, and the posterior obliquely forward and laterally.

Blood supply

- The deltoid is supplied by the posterior circumflex humeral artery and the deltoid branch of the thoracoacromial artery which branches from the axillary artery.[18]

Nerve supply

- The deltoid is innervated by the axillary nerve. The axillary nerve originates from the anterior rami of the cervical nerves C5 and C6, via the superior trunk, posterior division of the superior trunk, and the posterior cord of the brachial plexus.[rx]

Causes of Deltoid Pain

Deltoid strains can be caused by numerous mechanisms. Most commonly they result from overuse of the muscle without adequate rest. This can lead to discomfort in the area of the deltoid muscle with associated swelling and loss of function. A forced eccentric contraction of the shoulder (lengthening of the muscle belly while contracting), can lead to strain of the deltoid muscle (ie: doing a “negative “while weight lifting). Less commonly, a direct traumatic blow to the shoulder can cause a deltoid strain.

- Trauma – Injuries to the trapezius, such as a muscle tear from placing too much force on the muscle, can lead to pain.

- Repetitive stress – Repeating the same shoulder motions, again and again, can stress your trapezius muscles and tendons. Baseball, tennis, rowing, and weightlifting are examples of sports activities that can put you at risk for overuse tears. Many jobs and routine chores can cause overuse of tears, as well.

- Lack of blood supply – As we get older, the blood supply in our trapezius lessens. Without a good blood supply, the body’s natural ability to repair tendon damage is impaired. This can ultimately lead to a tendon tear.

- Bone spurs – As we age, bone spurs (bone overgrowth) often develop on the underside of the acromion bone. When we lift our arms, the spurs rub on the trapezius muscle. This condition is called shoulder impingement, and over time will weaken the tendon and make it more likely to tear.

- Sudden forceful fall down

- Road traffic accident

- Falls – Falling onto an outstretched hand is one of the most common causes of injury.

- Sports injuries – Many Injury occurs during contact sports or sports in which you might fall onto an outstretched hand — such as in-line skating or snowboarding.

- Motor vehicle crashes – Motor vehicle crashes can cause necks of femur fracture to break, sometimes into many pieces, and often require surgical repair.

- Have osteoporosis – a disease that weakens your bones

- Eave low muscle mass or poor muscle strength – or lack agility and have poor balance (these conditions make you more likely to fall)

- Walk or do other activities in the snow or on the ice – or do activities that require a lot of forwarding momenta, such as in-line skating and skiing

- Wave an inadequate intake of calcium or vitamin D

- Football or soccer, especially on artificial turf

- Rugby

- Horseback riding

- Hockey

- Skiing

- Snowboarding

- In-line skating

- Jumping on a trampoline

Symptoms of Deltoid Pain

Depending on the cause of your shoulder pain you may experience:

- pain deep in the shoulder joint, in the back or the front of the shoulder and the upper part of the arm. Sometimes the pain in the shoulder can be described as a ‘catching pain’. The location and type of pain is likely to relate to the structure causing the pain

- reduced movement, and pain when moving your shoulder.

- weakness of the shoulder/upper arm. Depending on the condition, there may be a sensation of the joint slipping out and back into the joint socket, or the shoulder can become completely dislodged (dislocated)

- sensations of pins and needles (tingling) and burning pain. This is more likely to be associated with nerves from the neck than the shoulder joint itself.

- lack of movement after a shoulder dislocation. This is usually due to pain. Complete rotator cuff tears and injury to the axillary nerve both cause weakness in moving the arm away from the body. These problems require close clinical examination.

Symptoms of a Deltoid Contusion

- Pain in the muscle after impact.

- Pain and difficulty when lifting the arm to the side.

- Tender to touch the muscle.

- Bruising appears.

- There may be some swelling.

Diagnosis of Deltoid Pain

The grades of deltoid strain are described below

Grade 1

- Tightness in the muscles.

- Mild pain in the deltoid

- The general function is not a problem.

- Increase in pain when weight-bearing with the arms.

Grade 2

- Occasional twinges of pain during activity.

- You may notice swelling.

- Pressing into the deltoid itself can cause pain.

- Lifting your arm up to the front, side or back against resistance can cause pain.

Grade 3

- Unable to move your arm.

- Severe pain.

- Swelling.

- Contracting the muscle is painful and there may be a bulge or gap in the muscle.

Or

When the deltoid muscle is injured, a person may feel pain or tenderness at the front, side, or back of the shoulder, especially when lifting the arm. In some cases, the deltoid muscle may be torn and cause swelling and bruising.

Strains are given a grade of 1–3, according to their severity:

- Grade 1 – These mild strains are characterized by tightness in the muscle and minimal swelling. Using the arm may produce slight pain, but the range of movement is often not restricted.

- Grade 2 – Increased pain, swelling, and limited movement are typically present with a grade 2 strain. In many cases, doing push-ups, presses, or lifting the arm in any direction can cause pain.

- Grade 3 – These serious injuries can cause severe pain, swelling, and a muscle bulge or gap. Due to the pain, the movement of the arm may be severely limited or impossible.

Diagnosing shoulder pain

Health practitioners who treat shoulder pain are trained to investigate and identify the exact cause of the condition or injury causing the pain. They will do this by:

- asking about your shoulder pain, including potential causes (e.g. recent injuries, other health conditions), if you have had shoulder pain before, things that make your pain worse, things that make it better

- conducting a thorough physical exam.

- From this information, they can work out the likelihood of particular structures in the shoulder being involved. Sometimes they will suggest that investigations or tests may be needed.

X-ray -m X-rays provide images of your bones and joints. They can show any changes caused by arthritis in the shoulder joint (e.g. bone spurs, narrowed joint space) or fractures. However, x-rays don’t show any changes or problems with your soft tissues (e.g. muscles, tendons).

Ultrasound – Ultrasounds are typically used to investigate your rotator cuff tendon for inflammation, tears or rupture. While it can be a helpful tool to use and can provide clues to identify the source of your pain, a diagnosis can’t be made using the ultrasound alone. If an ultrasound is ordered, then an x-ray should also be arranged. Both tests will provide more complete information about the state of your joints and the tendon.

CT and MRI – Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans are usually not the first test used to investigate shoulder pain. They may be used when a fracture is suspected or an accident is involved. These scans will help determine the extent of the injury and whether further assessment and treatment by a surgeon is needed.

Treatment of Deltoid Pain

Non-Pharmacological

- Rest – Rest, ice and heat are the initial steps to take to rehabilitate your deltoid muscles. Resting allows the muscle strain to heal, while ice reduces the inflammation and dulls your pain. Apply ice on a 15-minute on, 15-minute off schedule for the first day for grade 1 strains. Grade 1 strains are injuries that feel tight but do not produce pain or visible swelling of the shoulder area. Continue icing for several days for grade 2 and 3 strains. Strains of this severity will cause pain and hamper your mobility. Introduce heat to the shoulder muscles after the first 24 hours with a grade 1 injury and after 3 to 5 days for injuries classified as grades 2 or 3.

- Stretching and Strengthening – Stretching and strengthening your deltoids can help you recover from an injury and prevent future strains. Stretching can begin as soon as you are pain-free, and include the barbell stretch. Stand with your arms at your sides. Bring your arms up to shoulder height, keeping your elbows straight and arms out in front of you. Wrap one end of a resistance band around your left foot and hold the other end in your right hand to strengthen a right-hand deltoid injury reverse the directions to strengthen your left deltoid. Start with your right hand down at your side with your elbow straight. Keeping your elbow straight, pull against the band as you extend your arm up and out from your body. Picture yourself imitating an airplane with your arm outstretched at your side. Your hand should be shoulder level. Slowly bring your arm back down to your side.

- Massage – Sports massage may be a part of your rehab program. A sports massage, administered by a certified professional, keeps your muscles loose and limber and warms the injured tissues. Grade 1 deltoid injuries may be massaged after the first two days of rest and icing; more severe strains or tears may require up to a week’s healing time before the massage is possible.

- Ultrasound – Grade 3 deltoid injuries can benefit from more advanced rehab techniques, including ultrasound and electrical stimulation. These types of treatments must be performed by certified professionals and may include your athletic trainer or physical therapist. Ultrasound treatments send sound waves into the deltoid muscle; electrical stimulation provides the injured tissues a low-grade electrical current. Both of these treatments can reduce pain and inflammation.

Medication

In Severe Condition of the deltoid Muscle Injury

- Antibiotic – Cefuroxime or Azithromycin, or Flucloxacillin or any other cephalosporin/quinolone antibiotic must be used to prevent infection or clotted blood remove to prevent furthers swelling and edema. Antibiotics and tetanus vaccination may be used if the bone breaks through the skin creating immunization.

- NSAIDs – Prescription-strength drugs that reduce both pain and inflammation. Pain medicines and anti-inflammatory drugs help to relieve pain and stiffness, allowing for increased mobility and exercise. There are many common over-the-counter medicines called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). They include and Ketorolac, Aceclofenac, Naproxen, Etoricoxib.

- Corticosteroids – Also known as oral steroids, these medications reduce inflammation.

- Cortisone injections – First-line nonoperative management also includes the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs) medications in conjunction with PT modalities to rapidly reduce pain.

- Muscle Relaxants – These medications provide relief from associated muscle spasms or injury

- Neuropathic Agents – Drugs(pregabalin & gabapentin) that address neuropathic—or nerve-related—pain. This includes burning, numbness, and tingling.

- Opioids – Also known as narcotics, these medications are intense pain relievers that should only be used under a doctor’s careful supervision.

- Topical Medications – These prescription-strength creams, gels, ointments, patches, and sprays help relieve pain and inflammation through the skin.

- Calcium & vitamin D3 – To improve bone health and healing fracture. As a general rule, men and women age 50 and older should consume 1,200 milligrams of calcium a day, and 600 international units of vitamin D a day.

- Glucosamine & Diacerein, Chondroitin sulfate – can be used to tightening the loose tendon, cartilage, ligament, and cartilage, ligament regenerates cartilage or inhabits the further degeneration of cartilage, ligament.

- Dietary supplement -to remove general weakness & healing and improved health.

- Antidepressants – A drug that blocks pain messages from your brain and boosts the effects of endorphins (your body’s natural painkillers).

- Menthol – provides deep penetrating pain relief with a nice cooling sensation

- Vitamin B1, B6, B12– promotes normal nerve function

- Vitamin E – anti-inflammatory, enhances circulation, hydrates the skin

- Aloe vera – anti-inflammatory properties, soothes the skin

- Tea Tree – enhances the penetration of ingredients

- MSM – supports healthy connective tissues, anti-inflammatory

- Ilex Leaf Extract – increases circulation, skin conditioner

- Botulinum toxin injections – to her trapezius muscles, which considerably reduced pain and spasm. This clinical improvement lasted 3 months. Ongoing injections as required are planned.

Exercises

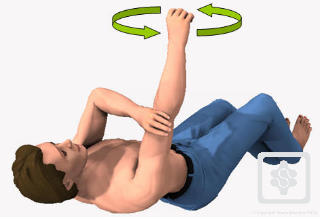

- Supine active-assisted – Lie down flat on your back, with a pillow supporting your head.

Bend your elbow as far as possible. Then raise your arm to 90 degrees vertical, using the stronger arm to assist if necessary. Once you have got to 90 degrees, you can straighten your elbow. Hold your arm in this upright position with its own strength. - Circles – Slowly with your fingers, wrist and elbow straight move the arm in small circular movements clockwise and counterclockwise. Gradually increase the circle as comfortable (this may take a few weeks to increase to bigger and bigger circles).

- Progress to lightweight – As you get more confidence in controlling your shoulder movement, a lightweight e.g. a tin of beans or small paperweight should be held in the affected hand.

- Progress to Sitting and Standing – Having more confidence in controlling your shoulder movement gradually goes from lying down to sitting and eventually standing. At this stage, you may recline the head of your bed or put some pillows underneath your back to recline your position. Repeat the same exercise again, this time against some gravity. Start again from holding your arm in the upright position with its own strength. Start first without any weights and progress to use the same lightweight you used before in the lying down position.

- Resisted Exercise – For re-education of concentric contracture of the deltoid muscle. Make a fist with the hand of the affected side. The flat hand of the opposite side is providing resistance. Push your affected side hand against resistance from the other hand. Whilst doing this, you will notice that you can fully elevate your arm (above your head). Repeat these exercises in order to ‘learn’ and re-educate your Deltoid muscle to perform this ‘concentric contracture’ even without pushing against your other arm.

Exercises

Supine active-assisted

- Lie down flat on your back, with a pillow supporting your head.

- Bend your elbow as far as possible. Then raise your arm to 90 degrees vertical, using the stronger arm to assist if necessary. Once you have got to 90 degrees, you can straighten your elbow.

- Hold your arm in this upright position with its own strength.

- Circles: Slowly with your fingers, wrist and elbow straight move the arm in small circular movements clockwise and counterclockwise. Gradually increase the circle as comfortable (this may take a few weeks to increase to bigger and bigger circles).

-

- Secondly move the arm forwards and backwards in line with the outside leg (gentle movement from both sides of the arm upright position.)

- Keep the movements smooth and continuous for 5 minutes or until fatigue.

- As you get more confidence in controlling your shoulder movement, gradually increase the range of movement until your arm will move from the side of your thigh to above your head, touching the bed, and return.

Progress to lightweight:

- As you get more confidence in controlling your shoulder movement, a lightweight e.g. a tin of beans or small paperweight should be held in the affected hand.

- Repeat as above (5 and 6).

Progress to sitting and standing:

- Having more confidence in controlling your shoulder movement gradually go from lying down to sitting and eventually standing.

- At this stage you may recline the head of your bed or put some pillows underneath your back to recline your position.

- Repeat the same exercise again, this time against some gravity.

- Start again from holding your arm in the upright position with its own strength.

- Repeat as above (5, 6 and 7).

- Start first without any weights and progress to use the same lightweight you used before in the lying down position.

Resisted exercise:

- For re-education of concentric contracture of the deltoid muscle.

- Make a fist with the hand of the affected side. The flat hand of the opposite side is providing resistance. Push your affected side hand against resistance from the other hand. Whilst doing this, you will notice that you can fully elevate your arm (above your head).

- Repeat these exercises in order to ‘learn’ and re-educate your Deltoid muscle to perform this ‘concentric contracture’ even without pushing against your other arm.

- You should repeat these exercises X 10 in a session, 3 to 5 sessions per day.

- Stop exercising if your pain increases or you feel unwell.

- You should expect to see some improvement by 6 and 12 weeks.

Surgical Considerations

The deltoid is a significant factor when considering the anterior surgical approach to gain access to the shoulder joint. Some of these technical procedures include, but are not limited to the following:

- Open Bankart repair/capsular reconstructions – indicated in the setting of recurrent anterior (or other directional) instability of the shoulder

- Shoulder arthroplasty – indicated for cases of post-traumatic deformity, advanced degenerative arthritis, and/or avascular necros includes hemiarthroplasty, total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA), reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (TSA)

- The long head of the biceps tendon (LHBT) repair- versus tenotomy versus tenodesis procedures indicated in the setting of either LHBT/bicipital groove instability or advanced/end-stage LHBT tendinopathy and degeneration[rx][rx]

- Rotator cuff repair – contemporary indications remain somewhat controversial although most of these procedures are now being performed arthroscopically popular approaches (as opposed to the deltopectoral approach) include the mini-open approach (lateral deltoid-splitting approach)

- Deltopectoral (DP) approach – When marking out the anatomic landmarks for the DP approach, the coracoid process is marked on the skin to plan out the trajectory for the surgical incision. From there, an incision is made which follows over the deltopectoral groove. The deltoid and pectoralis major muscle fibers are appreciated, and this most often includes direct visualization of a fat stripe which includes the cephalic vein in the center of the incision/approach. The deltoid is retracted laterally while the pectoralis major muscle is retracted medially. The cephalic vein is retracted either laterally or medially (depending on surgeon preference).[rx]

- Other approaches – Other surgical approaches that involve the deltoid are the anterolateral and direct lateral approach to the shoulder. A modified anterolateral approach can be preferred over the more anterior approach for humeral fractures because this may facilitate access to the specific fracture fragments.[rx]

REferences

.gif)