May 23, 2021

Adipose Tissue – Anatomy, Types, Functions

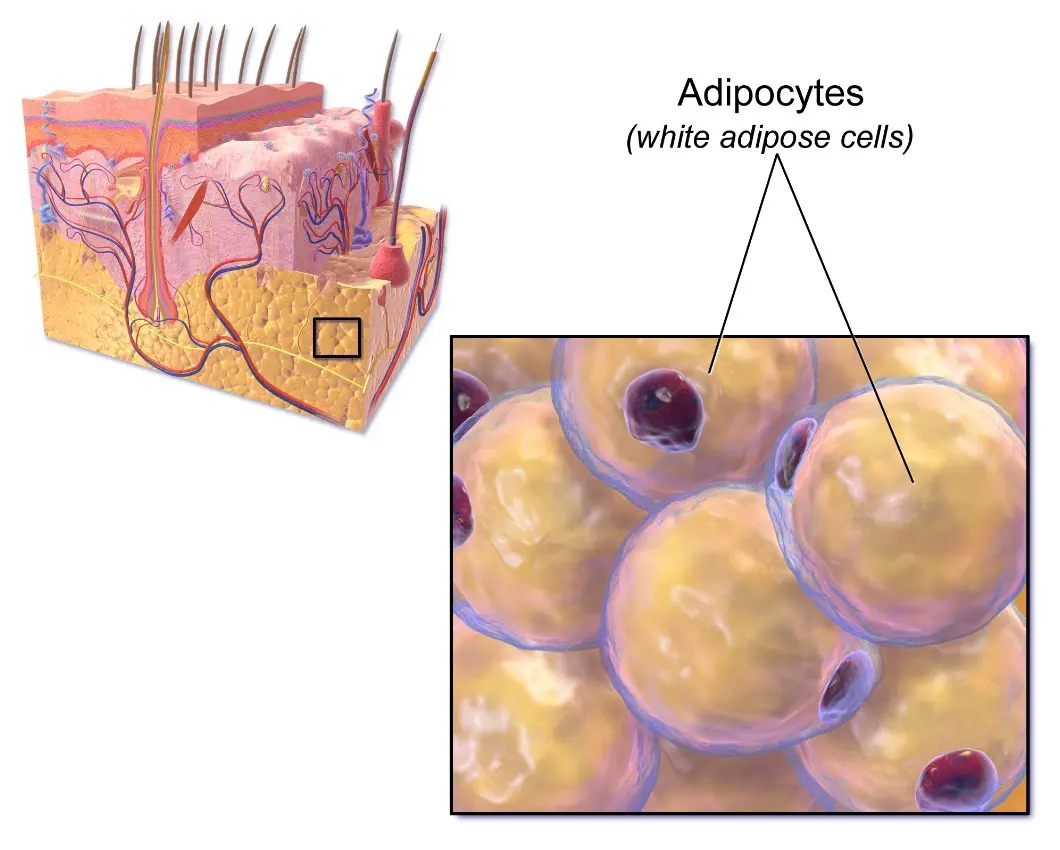

Adipose tissue is a specialized type of connective tissue that has both structural and highly complex metabolic functions, including energy storage, glucose homeostasis, and a multitude of endocrine capabilities. Multiple hormones, growth factors, and cytokines are expressed by adipocytes and their associated stromal cells and macrophages. There are three types of adipose tissue, white adipose tissue, brown adipose tissue, and beige or “brite” adipose tissue, which is a transitional form. Brown adipose tissue is present mostly in the fetus and in young children, and its main purpose is thermogenesis. Small deposits of brown adipose tissue persist into adult life. White adipose tissue is the major adipose tissue in adults, and it plays a role in several disease states, most notably obesity, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes.

Adipose tissue is a type of loose connective tissue composed mainly of cells called adipocytes.

Composition

- Adipocytes

- Stromal vascular fraction (SVF):

- Preadipocytes

- Fibroblasts

- Vascular endothelial cells

- Immune cells (major—adipose tissue macrophages)

Types of adipose tissue

Two classic types:

- White adipose tissue:

- Predominant type in adults

- Major source of energy, stored as triglycerides

- Contain single large lipid droplet (unilocular)

- Brown adipose tissue:

- Brown color due to increased vascularity and more mitochondria

- Present in large amounts during fetal life (~ 5% of body mass of newborn)

- Persists into adult life in much smaller amounts

- Contains a large amount of small lipid droplets (multilocular)

- Generates body heat

3rd, recently described, transitional type:

- Beige, “inducible,” or “brite” (= “brown in white”) adipose tissue

- Transitional/transformation phase, when white adipose tissue converts to brown adipose tissue (browning of white adipose tissue) or vice versa by differential gene expression, in response to thermogenic needs

Anatomic distribution

- Subcutaneous fat: beneath the skin

- Visceral fat: around internal organs

- Yellow bone marrow

- Intermuscular

- Breast tissue

- Distribution of brown adipose tissue:

- Fetus: prominent in the posterior cervical, axillary, suprailiac, and perirenal regions; also in the interscapular and deltoid regions

- Adults: persists around the kidneys, adrenals, aorta, mediastinum, and neck

Image: “Adipose Tissue” by Bruce Blaus. License: Public Domain, edited by Lecturio.

Development

Embryonic development

White adipose tissue:

- From 14 to 24 weeks of gestation:

- Adipocytes differentiate from perivascular undifferentiated mesenchymal cells or stem cells and progenitor cells and express peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor gamma/retinoid X receptor (PPARɣ/RXR) transcription factors.

- Adipocytes that arise in subcutaneous sites are molecularly and functionally different from those that arise in visceral sites.

- PPARɣ is considered the master regulator of adipogenesis.

- Precursor lipoblasts accumulate small lipid vacuoles in their cytoplasm, which fuse to become larger typical unilocular adipocytes of white adipose tissue.

Brown adipose tissue:

- Arises from skeletal myogenic progenitor cells, with similar close relationship with angiogenesis, and express the transcription factors PR domain–containing 16 (PRDM16) and PPARɣ coactivator 1 (PGC-1)

- Lipoblasts accumulate small lipid vacuoles, which remain separate to become typical multiloculated adipocytes of brown adipose tissue.

Postembryonic development

- Growth in number and size of adipocytes continues through puberty.

- New adipocytes may continue to form throughout the lifespan, especially if overnutrition (hyperalimentation) occurs.

- Stem cells and preadipocytes can divide; mature adipose cells cannot.

- Healthy versus unhealthy fat deposits:

- Subcutaneous white adipose tissue, especially that in the gluteal–femoral region, is considered metabolically healthy.

- Visceral white adipose tissue is associated with inflammation and increased risk of metabolic disease.

Gender differences

- Begin in early childhood

- Young girls have more adipose tissue than young boys

- After puberty, the distribution and physiology differ.

- Related to steroid hormone secretion

Females:

- Estrogens and progesterone promote localization of more fat in the lower body.

- Results in the gynecoid habitus of women (fat around hips, thighs, and buttocks)

- These fat deposits are subcutaneous.

- After menopause, women may store more fat around the waist and more visceral fat.

- Women continue to accumulate fat relative to body weight throughout the teen years.

- In premenopausal women, gluteal adipocytes are different because they:

- Undergo less lipolysis despite weight loss because cells have more catecholamine-sensitive α2 receptors, which inhibit lipolysis

- Have higher lipoprotein lipase (LPL) levels, so they capture more circulating triglycerides

- Are larger

Males:

- Fat in the lower body is reduced by androgens, producing an android distribution of fat.

- Store more abdominal (visceral) fat

- More prone to “central” (visceral obesity)

- Reach a peak in body fat content during early adolescence

Morphology and Histology

Morphology

White adipose tissue:

- Bright cadmium-like yellow, glistening, and greasy surface:

- Yellow color imparted by carotenoids found in many vegetables and fruits

- Reflects the active metabolism of fat in white adipose tissue

- Homogeneous diffuse appearance on cut section

- Thin septae dividing poorly defined lobules

- Thicker septae in areas of mechanical pressure (buttocks)

- Variation in color indicates a pathologic process:

- White or whitish-yellow: fat necrosis

- Pale yellow: lipoma

- Reddish to orangish-yellow: angiolipoma

- Whitish yellow to white firmer nodules: liposarcoma

Brown adipose tissue:

- Reddish-brown owing to abundant vascularity and numerous mitochondria within cells

- Glandular lobulated appearance

Beige: lighter brown than brown adipose tissue

Microscopic appearance

White adipose tissue:

- A mature white fat cell is spherical; size: up to 120 μm in diameter (compare to RBC = 7 μm, lymphocyte = 12–16 μm, hepatocyte = 20–30 μm)

- Cytoplasm: displaced and compressed to the perimeter by a single lipid vacuole; composed of 99% triglycerides

- Nucleus:

- Displaced peripherally by a lipid vacuole

- Oval, thin, and small, with central minute clear vacuole

- Adipocyte basement membrane: highlighted by reticulin and periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) stains

- Ill-defined lobules are separated by thin bands of collagen that are thicker in the buttocks.

- Stroma: capillaries (have intimate relationship with each adipocyte, similar to other endocrine organs), fibroblasts, macrophages, preadipocytes, stem cells

Brown adipose tissue:

- Organized into prominent lobules of cells

- Lobules are divided by septa containing blood vessels and nerves.

- Brown adipose tissue adipocytes:

- Multivacuolated and some univacuolated cells are present.

- Size: 25–40 μm (size varies, depending on nutritional status)

- Many large, round mitochondria (giving the granular appearance to cytoplasm)

- Nucleus: spherical, centrally located in the multilocular cells

Beige fat:

- The intermediate microscopic appearance between white adipose tissue and brown adipose tissue

- Varies depending on stage of induction

Physiology

Lipid storage

- White adipose tissue is the largest and most efficient store of energy (as triglycerides).

- LPL is synthesized by adipocytes and transferred to the adjacent endothelial cells.

- LPL on the luminal surface of endothelial cells hydrolyzes triglycerides from chylomicrons (from the intestine) and very-low-density lipoproteins (from the liver).

- Most of the released free fatty acids (FFAs) are taken up by the fat cells and re-esterified with glycerol phosphate within the adipocyte to form triacylglycerol.

- Triacylglycerols are stored within the adipocyte’s lipid droplet.

- Stored triacylglycerols are mobilized by lipase, which hydrolyzes stored triglycerides.

- Mobilization of triacylglycerols is controlled by both neural and hormonal factors:

- Norepinephrine:

- Activates lipase

- Denervated fat will continue to deposit even in a state of starvation.

- Insulin: stimulates lipid synthesis and inhibits lipase

- Glucagon and growth hormone: activate lipase

- Thyroid hormones:

- First increase lipogenesis

- Then cause lipolysis

- Cortisol’s effects depend on the physiologic context.

- Androgens are anti-adipogenic and estrogens are pro-adipogenic.

- Norepinephrine:

- The released FFAs may be re-esterified or released to the circulation and bound to albumin for transfer to other cells.

Endocrine function

Adipose tissue produces a number of hormones and cytokines.

- Leptin:

- Protein product of the ob gene

- Acts on the hypothalamus to increase energy expenditure and decrease appetite

- Adiponectin:

- Decreases gluconeogenesis and stimulates glucose uptake

- Modulates lipid catabolism

- Obesity is associated with reduced levels of adiponectin.

- Resistin:

- Increases low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels

- Associated with insulin resistance

- Proinflammatory effects

- Aromatase:

- Converts androstenedione to estrone, the major source of estrogen in men and postmenopausal women

- Expressed by the stromal cell fraction of adipose tissue and not the adipocytes

- Interleukin-6 (IL-6): (30% of IL-6 is from adipocytes, stromal cells, and resident macrophages):

- Stimulates hepatic triglyceride secretion and acute-phase reactants

- Increases platelet number and activity

- Increases expression of endothelial adhesion molecules

- Release is induced by tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) (implicated in anorexia of cancer).

- Other cytokines:

- TNF-α:

- Expressed in preadipocytes

- Blocks differentiation to mature adipocytes

- Fibroblast growth factor 1:

- From microvascular endothelial cells in white adipose tissue

- Stimulates preadipocyte differentiation and accumulation of triglycerides

- C3 and adipsin: proteins of the alternative complement pathway

- Plasminogen activator inhibitor 1 (PAI-1):

- Potent inhibitor of the fibrinolytic system (thromboembolic increased)

- Insulin induces the expression of PAI-1 by adipocytes.

- Obesity is associated with elevated levels.

- TNF-α:

Heat production

- The major function of brown adipose tissue: nonshivering thermogenesis; important for newborns

- Brown adipose tissue is very vascular and regulated by sympathetic stimulation.

- Many β1 and β2 adrenoreceptors regulate lipolysis and thermogenesis.

- Brown adipose tissue has more and larger mitochondria than white adipose tissue, and these possess a unique decoupling protein called “thermogenin” (the protein product of the UCP-1 gene).

- Thermogenin uncouples the oxidation of fatty acids from the generation of ATP.

- The resultant energy is dissipated as heat.

Other functions of adipose tissue

- Insulation from heat and cold by the subcutaneous layer

- Protective padding and structural support of visceral organs, mammary tissue, periorbital tissue, bone marrow, and in areas of mechanical stress (palms and soles of feet)

Clinical Relevance

- Obesity: a disease of excessive fat accumulation by both hypertrophy and hyperplasia of white adipose tissue: “Overweight” is defined as a BMI (the weight in kilograms divided by the square of the height in meters) of 25–29.9 and “obese” as a BMI ≥ 30. In the United States, the prevalence of obesity is ~ 40%, and that rate is increasing. Obesity is usually due to a sedentary lifestyle and an increased caloric intake, but there are also uncommon secondary causes. Obesity is associated with a number of disabilities, including:

- Hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes mellitus type 2

- Heart disease and dyslipidemia

- Cancer

- Osteoarthritis, gout

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, gallbladder disease, GERD

- Kidney disease

- Sleep apnea, dementia, depression

- Increased susceptibility to infections, including coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), influenza, and bacterial and fungal infections

- Skin changes, including stretch marks (striae), acanthosis nigricans (likely due to sustained hyperinsulinemia), hirsutism in women

- Metabolic syndrome diagnosed if 3 of the following 5 conditions are met:

- Hypertension

- Low levels of high-density lipoproteins

- Abdominal obesity

- Increased triglyceride levels

- Increased glucose levels

- Mnemonic PHATS 3/5: Pressure up, HDL low, Abdominal obesity, Triglycerides up, Sugars up

- Cellulite: a cosmetic problem that refers to linear depressed streaks (mattress phenomenon) or dimpling in the skin: Cellulite appears mostly on the thighs and buttocks, is more common in females, and results from an uneven dermal–hypodermal interface, with fibrous tissue surrounding the protruding adipous papillae. Cellulitis is less common in men because they have a smoother, strand-free dermal interface in the thigh and buttock areas.

- Lipodystrophies: rare congenital or acquired syndromes associated with a loss of healthy adipose tissue: Generalized lipodystrophy can be associated with diabetes, hepatic steatosis, pancreatitis, and metabolic syndrome.

- Fat necrosis: a condition associated with mechanical trauma (e.g., fat necrosis of the breast), inflammation (e.g., associated with acute pancreatitis), or ischemia (e.g., omental infarction).

- Fat embolism: an embolus composed of a cluster of adipocytes that enters the bloodstream and results in the blockage of blood flow: Fat emboli can present as pulmonary emboli after fractures of the long bones owing to the release of bone marrow fat.

- Calciphylaxis: skin and subcutaneous fat necrosis, with small blood vessel necrosis, calcium precipitation, and thrombosis: Calciphylaxis is a complication of dialysis and renal failure and is also seen in primary hyperparathyroidism This condition is often lethal.

- Panniculitis: inflammatory infiltrates in the subcutaneous adipose tissue: There are many causes of panniculitis, including steroid withdrawal, diabetes mellitus, tuberculosis, pancreatic disease, α1-antitrypsin deficiency, and autoimmune diseases. Inflammation may involve eosinophils, neutrophils, granulomas, and histiocytes with lymphophagocytosis, among others. Panniculitis may sometimes resolve without treatment, but it is often managed with antibiotics and anti-inflammatory drugs.

- Mesenteritis inflammation (mesenteric panniculitis): usually benign condition presenting as space-occupying lesion consisting of chronic inflammation with fat necrosis and proliferation of myofibroblasts involving single or multiple areas of the mesentery: Mesenteritis inflammation often presents with fever, but it can also be asymptomatic. This condition mostly affects middle-aged males. Prognosis is excellent, with most lesions regressing within 2 years.

- Tumors:

- Hibernoma: a benign neoplasm of brown adipose tissue: Hibernoma is the only pathologic lesion of brown adipose tissue. Tumors mostly occur in sites corresponding to the distribution of brown adipose tissue—the interscapular area, neck, mediastinum, and axilla. Hibernoma presents as a painless slow-growing subcutaneous mass, and it may achieve a size of up to 23 cm. Treatment is surgical excision.

- Lipoma: a benign neoplasm of adipocytes (white adipose tissue): Lipoma is the most common soft tissue tumor in adults. Many variants of lipoma exist, including angiolipoma, atypical lipoma, myxolipoma, and spindle cell lipoma. Lipoma usually presents as a painless soft tissue nodule. Diagnosis is usually established clinically and supported by tissue biopsy. The usual treatment is surgical excision, but smaller asymptomatic lesions may not require any treatment.

- Liposarcoma: a rare malignant tumor originating from adipocytes. This tumor is a kind of soft tissue sarcoma. Symptoms depend on the site of origin. Clinically, liposarcoma may be difficult to distinguish from a lipoma. Diagnosis is established with biopsy, and the mainstay of treatment is complete surgical excision.

References

Subscribe to the newsletter

Fames amet, amet elit nulla tellus, arcu.

2 Comments

Comments are closed.

Visitor Rating: 3 Stars

Visitor Rating: 5 Stars