Rheumatic Diseases is an umbrella term for conditions causing chronic, often intermittent pain affecting the joints and/or connective tissue. The study of, and therapeutic interventions in, such disorders is called rheumatology. The term “rheumatism”, however, does not designate any specific disorder but covers at least 200 different conditions.

Sources dealing with rheumatism tend to focus on arthritis, but “rheumatism” may also refer to other conditions causing chronic pain, grouped as “non-articular rheumatism”, also known as “regional pain syndrome” or “soft tissue rheumatism”. The term “Rheumatic Diseases” is used in MeSH to refer to connective tissue disorders.

Types of Rheumatic Diseases

Many rheumatic disorders of chronic, intermittent joint pain have historically been caused by infectious diseases. Their etiology was unknown until the 20th century and not treatable, like Lyme disease (in the Northern and Northeastern US), coccidiomycosis or Valley fever (in the Western US), and Chikungunya in India and a myriad of causes for postinfectious arthritis also known as reactive arthritis like, for example, the once very common rheumatic fever after Group A Streptococcus infection up to the rare Whipple’s disease.

Major rheumatic disorders currently recognized include

- Back pain

- Bursitis/Tendinitis of the shoulder, wrist, biceps, leg, knee cap (patella), ankle, hip, and Achilles tendon

- Capsulitis

- Neck pain

- Osteoarthritis

- Palindromic rheumatism has been theorized to be a form of rheumatoid arthritis.

Although these disorders probably have little in common in terms of their epidemiology, they do share three characteristics: they cause chronic, often intermittent pain, they are difficult to treat and are collectively very common.

Rheumatic diseases caused by autoimmunity include:

- Ankylosing spondylitis

- relapsing polychondritis

- systemic lupus erythematosus

- rheumatoid arthritis

- gout, inflammatory arthritis, pseudogout

- juvenile arthritis

- Sjögren syndrome

- scleroderma

- Polymyositis

- Dermatomyositis

- Behçet’s disease

- Psoriatic arthritis

Central Pain in Rheumatic Diseases

In a 2013 review article, researchers provided a deeper understanding of pain mechanisms in osteoarthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and rheumatoid arthritis. Their research suggests that disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs and surgery are unlikely to be effective as sole therapies when central pain versus peripheral pain is suspected in these patients.

The review appears in the January 28, 2013 online issue of Arthritis and Rheumatism.

In many rheumatologic conditions, chronic pain is an ongoing concern that results from the complex interaction of both central and peripheral nervous system signaling. Chronic pain in patients may involve pathology of the peripheral nerves, joints, muscles or skin. Currently, the selection of safe and effective pain therapies remains challenge for rheumatologists, as many of them have not received formal training on pain processing or management.

Led Kristine Phillips, M.D., of the University of Michigan, the goal of this review paper is provide an overview of central pain in the context of rheumatic diseases and to propose future directions for research. Lessons learned from this research will provide a better understanding of pain mechanisms and potentially lead to more personalized approaches to pain managements.

Concept of Centralized Pain

The phrase “central pain” was historically used to describe the condition resulting from individuals who developed pain following a stroke or spinal cord lesion. In these patients, “central” referred to the fact that the lesion leading to pain occurred within the central nervous system or CNS. More recently, the term central pain has expanded to describe any central nervous dysfunction or pathologic condition that contributes to the development or persistence of chronic pain. This new definition also encompasses the patient’s psychosocial aspects of pain perception. Moreover, the concept of centralized pain was originally thought to only apply to people with rare structural causes of pain or idiopathic pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia.

Central Pain Prone Phenotype

Various factors contribute to the development of central pain including, but not limited to:

- genetics

- early life trauma

- the family history of mood disturbances

- family history of chronic pain

- a personal history of chronic centrally-mediated symptoms such as fatigue or sleep disturbance

- cognition

- low pain threshold

- female sex

Centralized Pain in Rheumatic Diseases

It is estimated that 15-30% patients with rheumatic diseases also have fibromyalgia, which is much higher than the rate of fibromyalgia in the general population (~2%). This suggests that chronic rheumatoid arthritis may be a trigger for fibromyalgia.

Regarding osteoarthritis, the condition causes damage to bones and cartilage. This damage and inflammation of related structures is thought to predict pain symptoms. It is hypothesized that central factors (vs. peripheral factors) may play a critical role in the development of pain in osteoarthritis patients, which is further exacerbated by somatic symptoms such as poor sleep.

Fibromyalgia is suspected to be comorbid with systemic lupus erythematosus, a relationship that confounds the treatment and timely diagnosis of lupus. Surprisingly, the inflammation and damage from lupus are not the main culprits of pain in these patients, but rather the presence or absence of fibromyalgia. Fibromyalgia tends to occur in about 20% of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.

Finally, in contrast to osteoarthritis and fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis is characterized by systemic inflammation. Pain management in rheumatoid arthritis patients does not necessarily improve with disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, as these drugs target peripheral pathways. To the contrary, some evidence suggests that there are deficits in central pain processing in rheumatoid arthritis patients, which has implications for proper pain management.

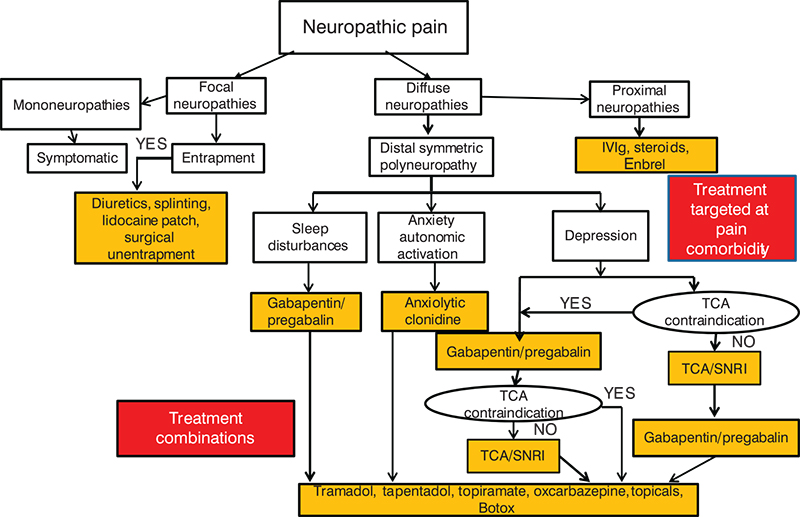

“Centrally targeted therapies have the potential to change the treatment of chronic pain in many diseases. Several classes of centrally acting agents (e.g., tricyclics, SSNRIs, gabapentinoids) may prove to be more effective in individuals with rheumatic disorders who have a central pain overlay than classes of drugs that are typically more effective for peripherally based nociceptive pain states (e.g., NSAIDs), but additional studies are needed to prove this. Newly developed pain cohort studies should identify these subsets of RA, SLE, and OA patients who are preferentially predisposed to respond to these centrally, in addition to peripherally acting treatments, including nonpharmacologic therapy,” wrote Phillips and colleagues.

Strategies for prevention of CVD in patients with rheumatic diseases

| Preventive strategy | Suggested interventions | References |

|

Regular screening, counseling and pharmacotherapy according to guidelines | Wajed et al 2004,van Doornum et al 2006 |

|

Interventions based on decision algorithms, guided by risk scores | Wilson et al 1998Yusuf et al 2003 |

|

Patient education, physiotherapy, and structured rehabilitation | Wikström et al 2005; Turesson et al 2007b |

|

Statins for patients with severe RA, despite moderate cholesterol levels | McCarey et al 2004; Van Doornum et al 2004 |

|

Use methotrexate as the drug of choice in RA Add TNF inhibitor in refractory patients | Choi et al 2002,Jacobsson et al 2005 |

Abbreviations: CVD, cardiovascular disease; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; TNF, tumor necrosis factor