Early Symptoms of Ischemic Cardiomyopathy/Ischemic Cardiomyopathy (ICM) is a term that refers to the heart’s decreased ability to pump blood properly, due to myocardial damage brought upon by ischemia. When discussing the term ICM, coronary artery disease (CAD) has to be addressed. CAD is a condition characterized by the formation of plaques in the coronary blood vessels, decreasing their capacity to supply nutrients and oxygen to the contractile heart muscle. ICM has a spectrum of clinical changes which eventually leads to congestive heart failure (CHF). Initially, there is a reversible loss of cardiac contractile function because of decreased oxygen supply to the heart muscle; however, when there is ischemia for a prolonged period, there is irreversible cardiac muscle damage resulting in cardiac remodeling.

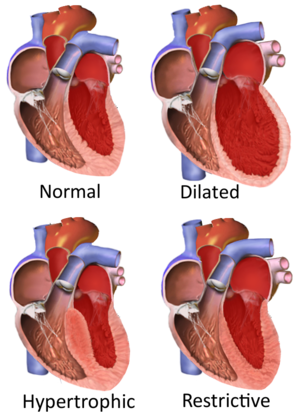

Types of cardiomyopathy include hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, dilated cardiomyopathy, restrictive cardiomyopathy, arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, and takotsubo cardiomyopathy (broken heart syndrome).[rx] In hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the heart muscle enlarges and thickens.[rx] In dilated cardiomyopathy, the ventricles enlarge and weaken.[rx] In restrictive cardiomyopathy, the ventricle stiffens.[rx]

Types of Ischemic Cardiomyopathy

Primary/intrinsic cardiomyopathies

Genetic

- Hypertrophic cardiomyopathy

- Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy (ARVC)

- LV non-compaction

- Ion Channelopathies

- Dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM)

- Restrictive cardiomyopathy (RCM)

Acquired

- Stress cardiomyopathy

- Myocarditis, inflammation of and injury to heart tissue due in part to its infiltration by lymphocytes and monocytes[rx][rx]

- Eosinophilic myocarditis, inflammation of and injury to heart tissue due in part to its infiltration by eosinophils[rx]

- Ischemic cardiomyopathy (not formally included in the classification as a direct result of another cardiac problem)[rx]

Secondary/extrinsic cardiomyopathies

Metabolic/storage

- Fabry’s disease

- Hemochromatosis

Endomyocardial

- Endomyocardial fibrosis

- Hypereosinophilic syndrome

Endocrine

- Diabetes mellitus

- Hyperthyroidism

- Acromegaly

Cardiofacial

- Noonan syndrome

Neuromuscular

- Muscular dystrophy

- Friedreich’s ataxia

Other

- Obesity-associated cardiomyopathy[rx]

Causes of Ischemic Cardiomyopathy

CAD most commonly causes ischemic cardiomyopathy. Lack of adequate blood supply is not able to meet the myocardial metabolic demands that lead to cell death, fibrosis, left ventricular enlargement, and dilation.

Modifiable

- Diabetes mellitus,

- Hypertension,

- Tobacco abuse,

- Hyperlipidemia,

- Obesity, and sedentary lifestyle

- Diabetes

- Atherosclerosis

- Vasospasm

- Inflammation of arteries

Non-modifiable

- Age, gender, and family predisposition

- Ischemic cardiomyopathy is the cause of more than 60% of all cases of systolic congestive heart failure in most countries of the world.[rx][rx]

Symptoms of Ischemic Cardiomyopathy

- Shortness of breath

- Swelling of the legs and feet (edema)

- Fatigue (feeling overly tired), inability to exercise, or carry out activities as usual

- Angina (chest pain or pressure that occurs with exercise or physical activity and can also occur with rest or after meals) is a less common symptom

- Weight gain, cough, and congestion related to fluid retention

- Palpitations or fluttering in the chest due to abnormal heart rhythms (arrhythmia)

- Fainting (caused by irregular heart rhythms, abnormal responses of the blood vessels during exercise, without apparent cause)

- Extreme fatigue

- Dizziness, lightheadedness, or fainting

- Chest pain and pressure, known as angina

- Heart palpitations

- Cough or congestion, caused by fluid in your lungs

- Difficulty sleeping

- Weight gain

Diagnosis of Ischemic Cardiomyopathy

After getting a detailed history and physical examination, there are several diagnostic modalities which can help with the diagnosis of ischemic cardiomyopathy.

-

Electrocardiogram (ECG) – important for identifying evidence of acute or prior myocardial infarction or acute ischemia, also rhythm abnormalities, such as atrial fibrillation.

-

Blood test – Cardiac troponin (T or I), complete blood count, serum electrolytes, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, liver function test and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). BNP (or NT-proBNP) level adds greater diagnostic value to the history and physical examination than other initial tests mentioned above.

-

Transthoracic Echocardiogram – to determine ventricular function and hemodynamics.

-

Chest x-ray – Simple and readily available test. It may show cardiomegaly and other findings of heart failure if a patient has progressed to that stage. Some x-ray findings in heart failure patients include pulmonary congestion, Kerley B lines, pleural effusion, and blunting of costophrenic angle.

-

ECG – Assesses the electrical activity of the heart. Useful in looking at the heart rate, rhythm, past/current ischemic episode, chamber enlargement, and information about heart’s electrical conductivity.

-

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) – This ultrasound-based imaging modality is useful in looking at cardiac anatomy and valvular function. It will assess for ventricular systolic/diastolic function, cardiac wall motion, pericardial pathology, and valvular function. All this information is useful in diagnosing ischemic cardiomyopathy.

-

Cardiac stress test – There are different stress tests available depending on the patient’s health, functional status, baseline heart rhythm, and exercise tolerance. The goal of these stress tests is to assess for cardiac ischemia. Some stress test modality can also provide information about myocardial viability.

-

Coronary angiography – allows for direct visualization of the coronary arteries, level of obstruction, and the blood flow to the myocardium. They also use it for percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with balloon angioplasty and coronary stents to allow for better blood flow across the occluded coronary artery.

-

CTCA – It uses computed tomography (CT) to take angiograms of the coronary arteries. Aids with the diagnosis of CAD in patients with low-intermediate risk.

-

Brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) test – BNP is synthesized in the ventricles, and it is secreted when the myocardial muscle has a high wall tension. Important biomarker for heart failure patients.

-

Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging- Differentiate ischemic from non-ischemic cardiomyopathies using Late gadolinium imaging. Late Gadolinium Enhancement (LGE) reflects irreversible damage to the myocardium and fibrosis. When LGE is absent in a dysfunctional segment of the myocardium, it implies the potential for recovery with time (stunning) or by medical treatment or revascularization.

Treatment of Ischemic Cardiomyopathy

Ischemic cardiomyopathy is managed primarily with an optimal goal-directed medical therapy (GDMA). However, for appropriate patient population cardiac intervention for revascularization is a common treatment option. Foremost, the patient will benefit from lifestyle modification which includes smoking cessation, exercise, and diet changes. Below are the medical interventions that can be done to optimize patients with ICM.

- Revascularization – Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy may benefit from revascularization. There was a 7% absolute reduction in overall mortality over a 10-year time between patients who had CABG versus GDMA[rx]. Revascularization followed by GDMA is recommended for these patients; however, it is important to assess their procedural candidacy. The primary goal is to reperfuse viable ischemic areas of the myocardium. However, a general test for myocardial viability is not recommended.

- Aspirin – It is shown to have major reductions in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality for patients with coronary heart disease. Historically, low dose aspirin (75 to 100 mg) once daily used; however, new data suggest that patients may need a higher dose (300 to 325 mg) if they weigh over 70 kg[rx].

- Beta-adrenergic antagonist (beta-blockers) – Atenolol, esmolol, labetalol, metoprolol, and propranolol. This group antagonizes the effects of epinephrine on beta receptors on the heart. B1 receptors are present in the heart, and when antagonized they decrease heart rate and heart muscle contractility that leads to decreasing oxygen consumption by the heart. B1 selective blockers decrease mortality in patients with heart failure, but should not be initiated when the patient is having acutely decompensated heart failure.

- High Potency Statin – Atorvastatin 40 to 80 mg or rosuvastatin 20 to 40 mg orally once daily. The mechanism of action is via HMG-CoA reductase inhibition. These medications inhibit the conversion of HMG-CoA to mevalonate, which is a cholesterol precursor. Statins decrease mortality in patients with coronary artery disease (CAD).

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors – Enalapril, lisinopril, captopril, and ramipril. This group of antihypertensive medications decreases mortality in patients with heart failure. The inhibition of the ACE leads to a decrease of angiotensin II which, when inhibited, decreases glomerular filtration rate by preventing constriction of efferent arterioles. This class of medication has cardio and renal protective effects when it comes to remodeling. An undesired added effect is the prevention of inactivation of bradykinin, which is a potent vasodilator that produces a cough and possibly angioedema in patients with C1 esterase inhibitor deficiency.

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers (ARB) – Valsartan, losartan, candesartan. This group has the same effect as the ACEI by selectively blocking angiotensin II from binding in its AT1 receptor. This group does not affect bradykinin and therefore is the medication of choice, replacing ACE inhibitors, when a patient complains of a cough or presents with angioedema after being started on ACEI.

- Hydralazine and nitrate – This group of medication can be used in patients who are unable to tolerate ACEI or an ARB.

- Angiotensin receptor neprilysin inhibitor (ARNI) – Recent clinical trial, PARADIGM-HF, showed a reduction in cardiovascular and all-cause mortality along with a reduction in heart failure hospitalization while on valsartan/sacubitril compared to enalapril[rx].

- Spironolactone – Shown to reduce morbidity and mortality in patients with heart failure (NYHA class III and IV) with LVEF 35% or less. It is a potassium-sparing diuretic that works as an antagonist to the aldosterone receptor at the nephron’s cortical collecting tubule.

- Digoxin – does not decrease mortality but is helpful in decreasing symptoms and hospitalizations in patients with congestive heart failure (CHF). Digoxin works by inhibiting the effects of the enzyme sodium/potassium ATPase in the heart muscle, stopping the sodium/calcium exchange, leaving more calcium inside the cell which increases contractility.

- ICD placement – Select patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy qualify for ICD to prevent sudden cardiac death (SCD). Patients with ischemic cardiomyopathy (evaluated at least 40 days post-MI or 3 months after revascularization), LVEF of 35% or less, and associated heart failure (HF) with New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional class II or III status, there is a class IA recommendation for ICD placement. Additionally, if a patient with ICM has LVEF of 30% or less and NYHA class I, ICD therapy is indicated for primary prevention of SCD.

- Biventricular pacing – If a patient has ischemic cardiomyopathy and LVEF 35% or less, then they may be a candidate for cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) if their heart failure symptoms are not controlled despite revascularization and GDMA.

Ultimately, a heart transplant is the only option when the disease progresses, and no alleviation is achieved with the intervention mentioned above.

Prevention

Up to 90% of cardiovascular disease may be preventable if established risk factors are avoided. Currently practiced measures to prevent cardiovascular disease include:

- Reduction in consumption of saturated fat – there is moderate-quality evidence that reducing the proportion of saturated fat in the diet, and replacing it with unsaturated fats or carbohydrates over a period of at least two years, leads to a reduction in the risk of cardiovascular disease.[rx]

- Stopping smoking and avoidance of second-hand smoke.[rx] Stopping smoking reduces risk by about 35%.[rx]

- Maintain a healthy diet, such as the Mediterranean diet. Dietary interventions are effective in reducing cardiovascular risk factors over a year, but the longer-term effects of such interventions and their impact on cardiovascular disease events are uncertain.[rx]

- At least 150 minutes (2 hours and 30 minutes) of moderate exercise per week.

- Limit alcohol consumption to the recommended daily limits;[rx] People who moderately consume alcoholic drinks have a 25–30% lower risk of cardiovascular disease. However, people who are genetically predisposed to consume less alcohol have lower rates of cardiovascular disease[rx] suggesting that alcohol itself may not be protective. Excessive alcohol intake increases the risk of cardiovascular disease and consumption of alcohol is associated with increased risk of a cardiovascular event in the day following consumption.[rx]

- Lower blood pressure, if elevated. A 10 mmHg reduction in blood pressure reduces risk by about 20%.[rx]

- Decrease non-HDL cholesterol. Statin treatment reduces cardiovascular mortality by about 31%.[rx]

- Decrease body fat if overweight or obese.[rx] The effect of weight loss is often difficult to distinguish from dietary change, and evidence on weight reducing diets is limited.[rx] In observational studies of people with severe obesity, weight loss following bariatric surgery is associated with a 46% reduction in cardiovascular risk.[rx]

- Decrease psychosocial stress.[rx] This measure may be complicated by imprecise definitions of what constitutes psychosocial interventions.[rx] Mental stress-induced myocardial ischemia is associated with an increased risk of heart problems in those with previous heart disease.[rx] Severe emotional and physical stress leads to a form of heart dysfunction known as Takotsubo syndrome in some people.[rx] Stress, however, plays a relatively minor role in hypertension.[rx] Specific relaxation therapies are of unclear benefit.