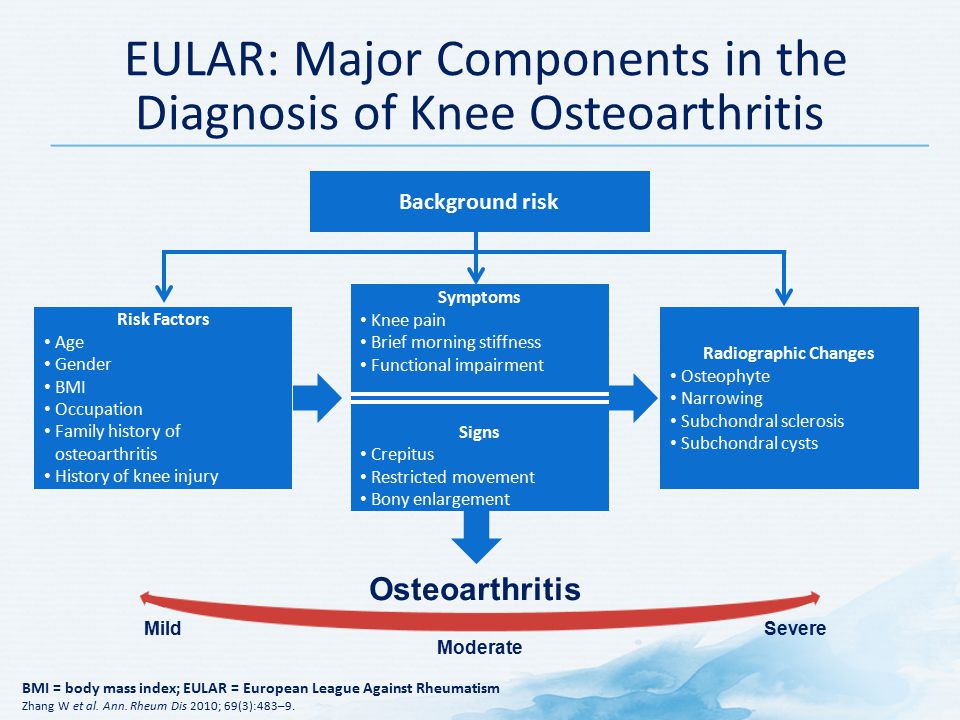

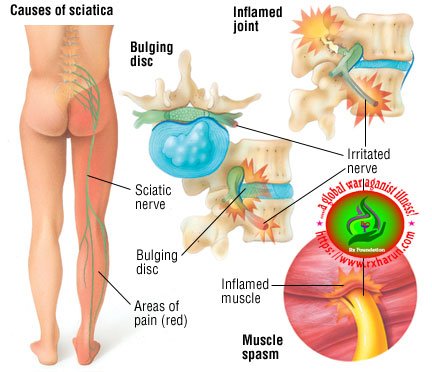

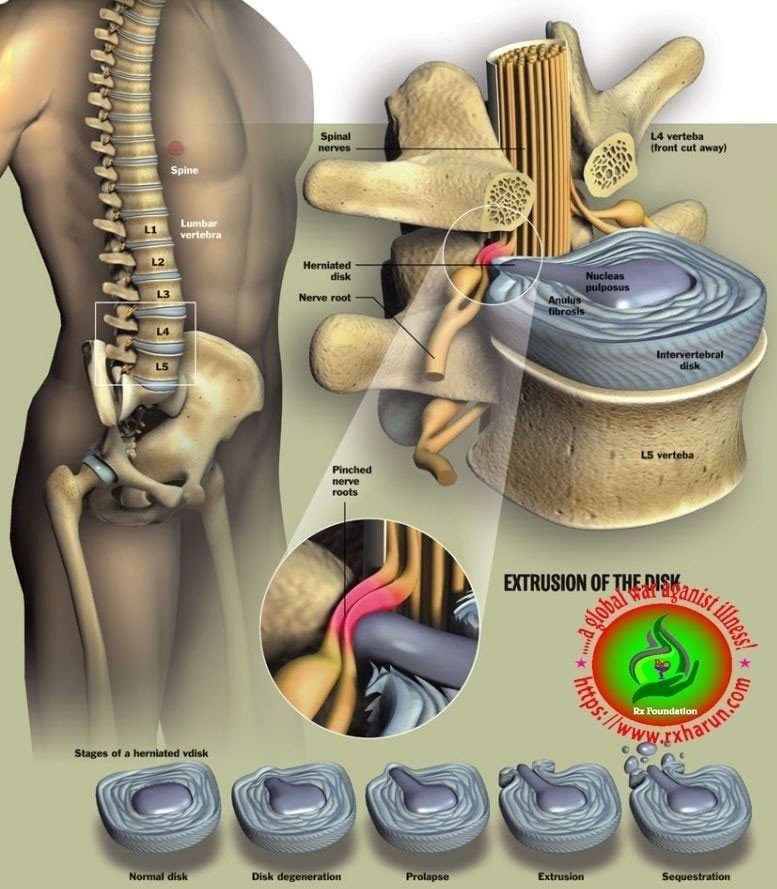

Treatment of Osteoarthritis of Knee (OA) a common disease of an aged population and one of the leading causes of disability. The incidence of knee OA is rising by increasing average age of the general population. Age, weight, trauma to joint due to repetitive movements, in particular, squatting and kneeling are common risk factors of knee OA. Several factors including cytokines, leptin, and mechanical forces are pathogenic factors of knee OA. In patients with knee pain attribution of pain to knee OA should be considered with caution. Since a proportion of knee OA is asymptomatic and in a number of patients identification of knee OA is not possible due to the low sensitivity of radiographic examination. In this review data presented in regard to prevalence, pathogenesis, risk factors.

Treatment of Osteoarthritis (OA) of Knee

Treatment for knee osteoarthritis can be broken down into non-surgical and surgical management. Initial treatment begins with non-surgical modalities and moves to surgical treatment once the non-surgical methods are no longer effective. A wide range of non-surgical modalities is available for the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. These interventions do not alter the underlying disease process, but they may substantially diminish pain and disability.

The non-pharmacological approach includes

- Education –Encourage patients to participate in self-management programmes (such as those conducted by the Arthritis Foundation in the United States and Arthritis Care in the United Kingdom), and provide resources for social support and instruction on coping skills.

- Weight loss – Encourage overweight patients with osteoarthritis of the hip and knee to lose weight through a combination of diet and exercise.Rx

- Exercise – increases aerobic capacity, muscle strength, and endurance and also facilitates weight loss. All people capable of exercise should be encouraged to take part in a low impact aerobic exercise programme (walking, cycling, or swimming or another aquatic exercise). Exercises to strengthen the quadriceps lead to reductions in pain and improvements in function.

- Physical therapy – consists of several strategies to facilitate the resolution of symptoms and improve functional deficits, including a range of motion exercise, muscle strengthening, muscle stretching, and soft tissue mobilization.

- Knee braces and orthotics – For those with the instability of the knee and varus misalignment, valgus bracing and orthotics shift the load away from the medial compartment and, in doing so, may provide relief of pain and improvement in function.Rx Though some research has shown that heel wedges can reduce medial compartment loads, there is no evidence that, used alone, they improve knee symptoms.Rx Appropriate supportive footwear should be worn by people who have osteoarthritis of the knee and hip.

-

Activity modification

-

Weight loss

-

Knee Bracing

The first-line treatment for all patients with symptomatic knee osteoarthritis includes patient education and physical therapy. A combination of supervised exercises and a home exercise program have been shown to have the best results. These benefits are lost after 6 months if the exercises are stopped. The American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons (AAOS) recommends this treatment.

www.rxharun.com

Medicine of Osteoarthritis (OA) of Knee

The goal of treatment is to decrease pain and increase mobility.

- Analgesics – Paracetamol (up to 4 g/day) is the oral analgesic of choice for mild to moderate pain in osteoarthritis. NSAIDs should be added or substituted in patients who respond inadequately and are sometimes the first choice because of greater efficacy and patients’ preference.13 There are, however, certain disadvantages of routinely using NSAIDs—for example, all NSAIDs (non-selective and COX 2 selective) are associated with potential toxicity, particularly in elderly people. COX 2 selective inhibitors have also been associated with an increased risk for cardiovascular disease. Rofecoxib, a COX 2 selective inhibitor, was recently withdrawn because of such concerns. In people with an increased gastrointestinal risk, nonselective NSAIDs plus a gastroprotective agent or a selective COX 2 inhibitor should be used. Opioid analgesics are useful alternatives in patients in whom NSAIDs are contraindicated, ineffective, or poorly tolerated. Topical formulations of NSAIDs and capsaicin may be helpful.

- Antidepressants – A Drugs that block pain messages from your brain and boost the effects of endorphins (your body’s natural painkillers).

- Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) Common pain remedies such as aspirin, acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and naproxen can offer short-term relief. All are available in low doses without a prescription. Other medications, including muscle relaxants and anti-seizure medications, treat aspects such as muscle spasms and damaged nerves.

- Corticosteroid injections – Your doctor will inject a steroid such as prednisone into your thumb joints. Steroids make inflammation go down. However, because of side effects, they are used sparingly

- Anesthetics – Used with precision, an injection of a “nerve block” can stop the pain for a time.

- Muscle Relaxants – These medications provide relief from spinal muscle spasms.

- Neuropathic Agents – Drugs(pregabalin & gabapentin) that address neuropathic—or nerve-related—pain. This includes burning, numbness, and tingling.

- Opioids – Also known as narcotics, these medications are intense pain relievers that should only be used under a doctor’s careful supervision.

- Topical Medications: These prescription-strength creams, gels, ointments, patches, and sprays help relieve pain and inflammation through the skin.

- Calcium & vitamin D3 – to improve bones health and healing fracture.

- Glucosamaine & diacerine – can be used to tightening the loose tension and regenerate cartilage or inhabit the further degeneration of cartilage.

- Muscle relaxants – such as cyclobenzaprine might be prescribed to relieve the discomfort associated with muscle spasms. However, these medicines might cause confusion in older people. Depending on the level of pain, prescription pain medicines might be used in the initial period of treatment.

- Over-the-counter – non-narcotic pain relievers and anti-inflammatory medications are usually the first choices of therapy for arthritis of the knee. Acetaminophen is a simple, over-the-counter pain reliever that can be effective in reducing arthritis pain that is following

- Glucosamine compounds – in particular, have attracted a great deal of attention, mostly in the lay press. Possibly as a function of this publicity, osteoarthritis is the leading medical condition for which people use alternative therapies.w6 Glucosamine and chondroitin seem to have the same benefit as placebo,Rxand there is controversy over whether they also have structure modifying benefits.

-

COX-2 inhibitors

-

Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate

-

Corticosteroid injections

-

Hyaluronic acid (HA)

Intra-articular Knee Injection Treatments

-

Viscosupplementation with hyaluronic acid (HA) – Injection into the knee with HA (similar to the main component in cartilage) has been reported to provide temporary pain relief for up to three months. Evidence to date on the use of HA has been contradictory, and recommendations regarding its use remain inconclusive[,2Rx ]Currently, the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons does not recommend using hyaluronic acid for patients with symptomatic end-stage osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee. There are no existing data that any of the HA injections will cause regression of osteophytes, subchondral bone remodeling, or regeneration of cartilage and meniscus in patients with substantial, irreversible bone and cartilage damage. Further investigations are required to determine whether high-molecular-weight and cross-linked preparations of HA have superior efficacy compared with other HA preparations or other currently available treatments. In addition, studies involving long-term outcomes of efficacy, safety, and economic cost-benefit analyses are needed.Rx Because of the paucity of data supporting the effectiveness of HA injections to justify their cost, careful patient selection and decreasing the use of HA among patients with end-stage knee OA may represent a substantial cost reduction without negatively affecting the quality of health care.Rx

-

Intra-articular corticosteroids – Intra-articular injections of corticosteroids have long been used to try to relieve symptoms from knee OA, but studies addressing their efficacy have been contradictory. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons guidelines for nonoperative treatment options for patients with OA of the knee does not recommend for or against the use of intra-articular corticosteroids into the knee.Rx Furthermore, a recent Cochrane systematic review concluded that clinically important benefits of one to six weeks remain unclear because of the overall quality of the studies, the heterogeneity between trials, and the presence of small-study effects.Rx

-

Intra-articular hyaluronan – Though the meta-analyses reviewing the efficacy of intra-articular hyaluronan are not in complete agreement, mainly because of variation in study methods, most suggest that the effect size is relatively small and the placebo response is significant.Rx

-

Cell-based therapies – Cell-based therapies for knee OA are in development stages. A recent systematic review suggested that intra-articular cellular injections for OA and focal cartilage defects in the human knee had positive results and seemed safe. However, improvement in patient symptoms was modest and a placebo effect could not be disregarded. The overall quality of the literature was poor; therefore, accurate assessment and optimization of these therapies will require further research. Rx Most of the studies analyzed reported on the use of autologous cellular therapies. Bone marrow-derived cells were the source chosen more often, followed by adipose-derived cells and blood stem cells.

-

Platelet-rich plasma – Multiple studies and systematic reviews have reported on the use of intra-articular PRP for the treatment of knee OA.Rx Initial observations support an inference that PRP appears to be safe. Although some transient pain or swelling has been reported after its use, these symptoms typically resolve within two to three days, and no long-term side effects have been reported. Use of PRP, especially a lower leukocyte concentration known as leukocyte-poor PRP, showed improved results compared with HA and placebo, showing beneficial effects of amelioration in pain and improvement in function about two months after application and lasting up to a year. Rx–Rx On the basis of the current evidence, although PRP injections have been demonstrated to more effectively reduce pain and improve overall physical function compared with control studies, the quality of evidence is lacking, and further research is required to establish the efficacy of using PRP as a treatment option.

-

Glucose Amaine with Chondroitin Sulphate – Glucosamine and chondroitin have been widely promoted as a treatment for OA. Glucosamine, an amino sugar, is thought to promote the formation and repair of cartilage. Chondroitin, a carbohydrate, is a cartilage component that is thought to promote water retention and elasticity and to inhibit the enzymes that break down cartilage. Both compounds are manufactured by the body. Glucosamine supplements are derived from shellfish shells; chondroitin supplements are generally made from cow cartilage.

-

Duloxetine – This antidepressant, which was evaluated for OA for the first time in these guidelines, may help with chronic pain. However, side effects like nausea, dry mouth, fatigue, constipation, and increased sweating may keep some people from taking it. Duloxetine is appropriate for people with OA of the knee and other joints. Whether people with knee-only OA and coexisting health conditions should take it is uncertain.

-

Capsaicin – This analgesic, which is derived from chili peppers, is better than a placebo at reducing pain, but it can cause side effects such as a burning sensation or skin redness. It’s appropriate for knee-only OA in people without existing health conditions, but uncertain in people with multi-joint OA and those with health conditions.

-

Opioid and narcotic analgesics – A review of 18 randomized controlled trials showed a significant reduction in pain and some improvement in physical function with the use of these strong pain relievers. However, these benefits were countered by significant side effects, including nausea, constipation, dizziness, sleepiness, and vomiting. Overall, about a quarter of patients treated with opioids—and particularly with strong drugs like oxycodone and oxymorphone—dropped out of studies because of side effects. The recommendation on both oral and patch forms of opioid pain relievers is “uncertain.”

-

Corticosteroid injections – Injecting corticosteroid compounds directly into affected joints can be useful for decreasing pain in the short term, although the effect tends to wear off after a few weeks. To maintain relief, you may need to have corticosteroid injections in the same joint every few months or use another treatment.

-

Hyaluronic acid injections – Hyaluronic acid is meant to supplement a natural substance that gives joint fluid its viscosity. Most of the studies conducted have been in patients with knee OA. Although the study outcomes differ, some do find the treatment relieves pain. Hyaluronic acid injections seem to reach their peak benefit 8 weeks after the shot is given, and the effect lasts for about 24 weeks. Side effects were minimal, including temporary pain and swelling at the injection site. Because of inconsistent study results, hyaluronic acid injections are “not appropriate” for people with OA of the hip and other joints, and “uncertain” for those with knee-only OA.

-

Risedronate (Actonel) – This bisphosphonate drug is better known for treating osteoporosis, but it may also reduce cartilage degeneration. More studies are needed to determine whether risedronate helps with symptoms, function, or OA disease progression. For now, the drug is deemed “not appropriate.”

-

Bracing – Knee braces are available for treatment of medial compartmental osteoarthritis (arthritis on the inside of the knee joint). These braces work by unloading the medial (inside) portion of the knee. These braces need to be custom made and therefore can be expensive.

-

Duloxetine – Normally used as an antidepressant, this medication is also approved to treat chronic pain, including osteoarthritis pain.

-

Disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (DMARDs) – are used to slow the progression of rheumatoid arthritis. Drugs like methotrexate, sulfasalazine, and hydroxychloroquine are commonly prescribed. In addition, biologic DMARDs like etanercept and adalimumab may reduce the body’s overactive immune response. Because there are many different drugs today for rheumatoid arthritis, a rheumatology specialist is often required to effectively manage medications.

-

Glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate – substances found naturally in joint cartilage, can be taken as dietary supplements. Although patient reports indicate that these supplements may relieve pain, there is no evidence to support the use of glucosamine and chondroitin sulfate to decrease or reverse the progression of arthritis.

- Avocado-soybean unsaponifiables – This nutritional supplement — a mixture of avocado and soybean oils — is widely used in Europe to treat knee and hip osteoarthritis. It acts as an anti-inflammatory, and some studies have shown it may slow down or even prevent joint damage.

- Alternative therapies – Many alternative forms of therapy are unproven but may be helpful to try, provided you find a qualified practitioner and keep your doctor informed of your decision. Alternative therapies to treat pain include the use of acupuncture and magnetic pulse therapy.

Strengthening Exercises

Knee extension

Straightening the knee against resistance will strengthen the quadriceps muscles at the front of the thigh. This can be achieved in a number of ways, including using ankle weights and resistance machines. One of the easiest ways involves using a resistance band

- The patient sits on a chair with one end of the band tied around their ankle and the other end around one of the chair legs.

- The band should be taut when the knee is bent at 90 degrees. The patient straightens the knee before slowly bending it and returning the foot back to the floor.

- Perform 10-15 repetitions and repeat this 2-3 times.

Knee flexion

Still using the resistance band:

- The patient lies on the floor with the band tied around one ankle and the other end attached to something sturdy, close to the floor. The band should be taught when the knee is straight

- The patient bends the knee to bring the heel towards the buttock as far as possible, and then slowly straightens the knee back again.

- Perform 10-15 repetitions and repeat this 2-3 times.

Calf raise

Calf raises are good for strengthening the Gastrocnemius muscle which is one of the two main calf muscles, but the only one which crosses the knee joint.

- The patient stands with the feet should width apart and close to a wall or chair which can be held for balance if required.

- The patient rises up on to the toes, keeping the knees straight, before slowly lowering the heels back to the floor.

- Perform 10-15 repetitions and repeat this 2-3 times.

- This exercise can be progressed by performing on one leg only.

Squats

Squats are really good exercises for strengthening all the main muscle groups of the legs and buttocks. They can start off as very shallow movements and progress until the knees reach a 90 degree angle at which point weights can be added.

- The patient stands with the feet shoulder width apart and back straight.

- The knees are then bent as if trying to sit on a chair.

- The back should remain straight and the knees should not move forwards past the toes.

- Perform 10-15 repetitions and repeat this 2-3 times.

Acupuncture – uses fine needles to stimulate specific body areas to relieve pain or temporarily numb an area. Although it is used in many parts of the world and evidence suggests that it can help ease the pain of arthritis, there are few scientific studies of its effectiveness. Be sure your acupuncturist is certified, and do not hesitate to ask about his or her sterilization practices.

Magnetic pulse therapy – is painless and works by applying a pulsed signal to the knee, which is placed in an electromagnetic field. Like many alternative therapies, magnetic pulse therapy has yet to be proven.

Nonsurgical Treatment

As with other arthritic conditions, initial treatment of arthritis of the knee is nonsurgical. Your doctor may recommend a range of treatment options.

Lifestyle modifications –Some changes in your daily life can protect your knee joint and slow the progress of arthritis.

- Minimize activities that aggravate the condition, such as climbing stairs.

- Switching from high impact activities (like jogging or tennis) to lower impact activities (like swimming or cycling) will put less stress on your knee.

- Losing weight can reduce stress on the knee joint, resulting in less pain and increased function.

- Physical therapy – Specific exercises can help increase the range of motion and flexibility, as well as help strengthen the muscles in your leg. Your doctor or a physical therapist can help develop an individualized exercise program that meets your needs and lifestyle.

- Assistive devices – Using devices such as a cane, wearing shock-absorbing shoes or inserts, or wearing a brace or knee sleeve can be helpful. A brace assists with stability and function and may be especially helpful if the arthritis is centered on one side of the knee. There are two types of braces that are often used for knee arthritis: An “unloader” brace shifts weight away from the affected portion of the knee, while a “support” brace helps support the entire knee load.

- Occupational therapy – An occupational therapist can help you discover ways to do everyday tasks or do your job without putting extra stress on your already painful joint. For instance, a toothbrush with a large grip could make brushing your teeth easier if you have finger osteoarthritis. A bench in your shower could help relieve the pain of standing if you have knee osteoarthritis.

- Other remedies – Applying heat or ice, using pain-relieving ointments or creams, or wearing elastic bandages to provide support to the knee may provide some relief from pain.

- Aerobic exercise – programs may make OA patients feel better, help reduces the joint pain, and make it easier for them to perform daily tasks. Exercise programs under medical supervision should be balanced with rest and joint care.[Rx] Aerobic programs truly border both clinical (rehabilitation) and home programs. Regardless of the setting, this program type was found to be effective for reducing pain in the hip and knee.[Rx] Patients are typically recommended to exercise between 50% and 70% target heart rate for a minimum of 30 min, 3 times a week, for overall weight management, health benefits, and a reduction in pain which was noted after a 6-month program.[Rx]

- Hydrotherapy (balneotherapy) – involves the use of water in any form or at any temperature (steam, liquid, ice) for the purpose of healing. In aquatic physical therapy or hydrotherapy, exercise activities are carried out in heated pools by a variety of providers.[Rx] Hydrotherapy/balneotherapy and aquatic therapy displayed positive results when conducted for testing a subject’s strength and flexibility. The results emphasized the role of these therapies in aiding normal walking and relieving joint pain.[Rx] The sessions typically are run from 6 to 48 weeks for the duration of 60 min and are conducted in a shallow pool with water temperatures ranging from 29°C to 34°C.[Rx]

Surgical Treatment

Your doctor may recommend surgery if your pain from arthritis causes disability and is not relieved with nonsurgical treatment. As with all surgeries, there are some risks and possible complications with different knee procedures. Your doctor will discuss the possible complications with you before your operation.

Arthroscopy – During arthroscopy, doctors use small incisions and thin instruments to diagnose and treat joint problems. Arthroscopic surgery is not often used to treat arthritis of the knee. In cases where osteoarthritis is accompanied by a degenerative meniscal tear, arthroscopic surgery may be recommended to treat the torn meniscus.

Cartilage grafting – Normal, healthy cartilage tissue may be taken from another part of the knee or from a tissue bank to fill a hole in the articular cartilage. This procedure is typically considered only for younger patients who have small areas of cartilage damage.

Synovectomy – The joint lining damaged by rheumatoid arthritis is removed to reduce pain and swelling.

Osteotomy – In a knee osteotomy, either the tibia (shinbone) or femur (thighbone) is cut and then reshaped to relieve pressure on the knee joint. Knee osteotomy is used when you have early-stage osteoarthritis that has damaged just one side of the knee joint. By shifting your weight off the damaged side of the joint, an osteotomy can relieve pain and significantly improve function in your arthritic knee.

Total or partial knee replacement (arthroplasty) – Your doctor will remove the damaged cartilage and bone, and then position new metal or plastic joint surfaces to restore the function of your knee.

Surgical Treatment Options

-

Osteotomy

-

Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA)

-

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA)

A high tibial osteotomy (HTO) may be indicated for unicompartmental knee osteoarthritis associated with malalignment. Typically an HTO is done for varus deformities where the medial compartment of the knee is worn and arthritic. The ideal patient for an HTO would be a young, active patient in whom arthroplasty would fail due to excessive component wear. An HTO preserves the actual knee joint, including the cruciate ligaments, and allows the patient to return to high-impact activities once healed. It does require additional healing time compared to an arthroplasty, is more prone to complications, depends on bone and fracture healing, is less reliable for pain relief, and ultimately does not replace cartilage that is already lost or repair any remaining cartilage. An osteotomy will delay the need for an arthroplasty for up to 10 years.

Indications for HTO

-

Young (less than 50 years old), active patient

-

Healthy patient with good vascular status

-

Non-obese patients

-

Pain and disability interfering with daily life

-

Only one knee compartment is affected

-

Compliant patient who will be able to follow postoperative protocol

Contraindications for HTO

-

Inflammatory arthritis

-

Obese patients

-

Knee flexion contracture greater than 15 degrees

-

Knee flexion less than 90 degrees

-

If the procedure will need greater than 20 degrees of deformity correction

-

Patellofemoral arthritis

-

Ligamentous instability

A UKA also is indicated in unicompartmental knee osteoarthritis. It is an alternative to an HTO and a TKA. It is indicated for older patients, typically 60 years or older, and relatively thin patients; although, with newer surgical techniques the indications are being pushed.

Indications for UKA

-

Older (60 years or older), lower demand patients

-

Relatively thin patients

Contraindications for UKA

-

Inflammatory arthritis

-

ACL deficiency

-

Fixed varus deformity greater than 10 degrees

-

Fixed valgus deformity greater than 5 degrees

-

Arc of motion less than 90 degrees

-

Flexion contracture greater than 10 degrees

-

Arthritis in more than one compartment

-

Younger, higher activity patients or heavy laborers

-

Patellofemoral arthritis

A TKA is the surgical treatment option for patients failing conservative management and those with osteoarthritis in more than one compartment. It is regarded as a valuable intervention for patients who have severe daily pain along with radiographic evidence of knee osteoarthritis.

Indications for TKA

-

Symptomatic knee OA in more than one compartment

-

Failed non-surgical treatment options

Contraindications for TKA

Absolute

-

Active or latent knee infection

-

Presence of active infection elsewhere in the body

-

Incompetent quadriceps muscle or extensor mechanism

Relative

-

Neuropathic arthropathy

-

Poor soft tissue coverage

-

Morbid obesity

-

Noncompliance due to major psychiatric disorder or alcohol or drug abuse

-

Insufficient bone stock for reconstruction

-

Poor health or presence of comorbidities that make the patient an unsuitable candidate for major surgery and anesthesia

-

Patient’s poor motivation or unrealistic expectations

-

Severe peripheral vascular disease

Advantages of UKA vs TKA

-

Faster rehabilitation and quicker recovery

-

Less blood loss

-

Less morbidity

-

Less expensive

-

Preservation of normal kinematics

-

Smaller incision

-

Less postsurgical pain and shorter hospital stay

Advantages of UKA vs HTO

-

Faster rehabilitation and quicker recovery

-

Improved cosmesis

-

Higher initial success rate

-

Fewer short-term complications

-

Lasts longer

-

Easier to convert to TKA

Natural Relief From Arthritis Pain

Arthritis Pain

Arthritis is a painful and degenerative condition marked by inflammation in the joints that causes stiffness and pain. Osteoarthritis, the most common type of arthritis, gets worse with age and is caused by wear and tear over the years.

Doctors traditionally treat arthritis with anti-inflammatory medications and painkillers. However, some medications cause side effects, and a natural approach to pain relief is becoming more popular. Remember to consult your doctor before trying these natural remedies.

Your weight can make a big impact on the amount of pain you experience from arthritis.

Extra weight puts more pressure on your joints—, especially your knees, hips, and feet. Reducing the stress on your joints by losing weight will improve your mobility, decrease pain, and prevent future damage to your joints.

Get More Exercise

There are more benefits to exercise than just weight loss. Regular movement helps to maintain flexibility in your joints. Weight-bearing exercises like running and walking can be damaging. Instead, try low-impact exercises like water aerobics or swimming to flex your joints without adding further stress.

Use Hot and Cold Therapy

Simple hot and cold treatments can make a world of difference when it comes to arthritis pain. Long, warm showers or baths—especially in the morning—help ease stiffness in your joints. Use an electric blanket or heating pad at night to keep your joints loose and use moist heating pads.

Cold treatments are best for relieving joint pain. Wrap a gel ice pack or a bag of frozen vegetables in a towel and apply it to painful joints for quick relief

Use Meditation to Cope With Pain

Meditation and relaxation techniques may be able to help you reduce pain from arthritis by reducing stress and enabling you to cope with it better. According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), studies have found that the practice of mindfulness meditation is helpful for some people with painful joints. Researchers also found that those with depression and arthritis benefitted the most from meditation.

Include the Right Fatty Acids in Your Diet

Everyone needs omega-3 fatty acids in their diets for optimum health. However, these fats may also help your arthritis. Fish oil supplements, which are high in omega-3s, may help reduce joint stiffness and pain.

Another fatty acid that can help is gamma-linolenic acid or GLA. It’s found in the seeds of certain plants like evening primrose, borage, hemp, and black currants. You can also buy the oils of the seeds as a supplement. However, be sure to check with your doctor before taking them.

Turmeric to Dishes

Turmeric, the yellow spice common in Indian dishes, contains a chemical called curcumin that may be able to reduce arthritis pain. The secret is its anti-inflammatory properties.

The NIH reports that turmeric given to lab rats reduced inflammation in their joints. Research on humans is scarce, but it can’t hurt to add this tasty spice to your dinners.

Massage

According to the Arthritis Foundation, regular massaging of arthritic joints can help reduce pain and stiffness and improve your range of motion. Work with a physical therapist to learn self-massage, or schedule appointments with a massage therapist regularly

Your massage therapist should be experienced with working on people who have arthritis. Check with your doctor for a recommendation.

Consider Herbal Supplements

There are many kinds of herbal supplements on the market that claim to be able to reduce joint pain. Some of the herbs touted for arthritis pain include boswellia, bromelain, devil’s claw, ginkgo, stinging nettle, and thunder god vine.

Always talk to your doctor before trying a new supplement to avoid side effects and dangerous drug interactions.

Complications

Complications associated with non-surgical treatment are largely associated with NSAID use.

Common Adverse Effects of NSAID Use

-

Stomach pain and heartburn

-

Stomach ulcers

-

A tendency to bleed, especially while taking aspirin

-

Kidney problems

Common Adverse Effects of Intra-Articular Corticosteroid Injection

-

Pain and swelling (cortisone flare)

-

Skin discoloration at the site of injection

-

Elevated blood sugar

-

Infection

-

Allergic reaction

Common Adverse Effects of Intra-Articular HA Injection

-

Injection site pain

-

Muscle pain

-

Trouble walking

-

Fever

-

Chills

-

A headache

Complications Associated with HTO

-

Recurrence of deformity

-

Loss of posterior tibial slope

-

Patella Baja

-

Compartment syndrome

-

Peroneal nerve palsy

-

Malunion or nonunion

-

Infection

-

Persistent pain

-

Blood clot

Complications Associated with UKA

-

Stress fracture of the tibia

-

Tibial component collapse

-

Infection

-

Osteolysis

-

Persistent pain

-

Neurovascular injury

-

Blood clot

Complications Associated with TKA

-

Infection

-

Instability

-

Osteolysis

-

Neurovascular injury

-

Fracture

-

Extensor mechanism rupture

-

Patellar maltracking

-

Patellar clunk syndrome

-

Stiffness

-

Peroneal nerve palsy

-

Wound complications

-

Heterotopic ossification

-

Blood clot

References