By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- List the structures that make up the respiratory system

- Describe how the respiratory system processes oxygen and CO2

- Compare and contrast the functions of upper respiratory tract with the lower respiratory tract

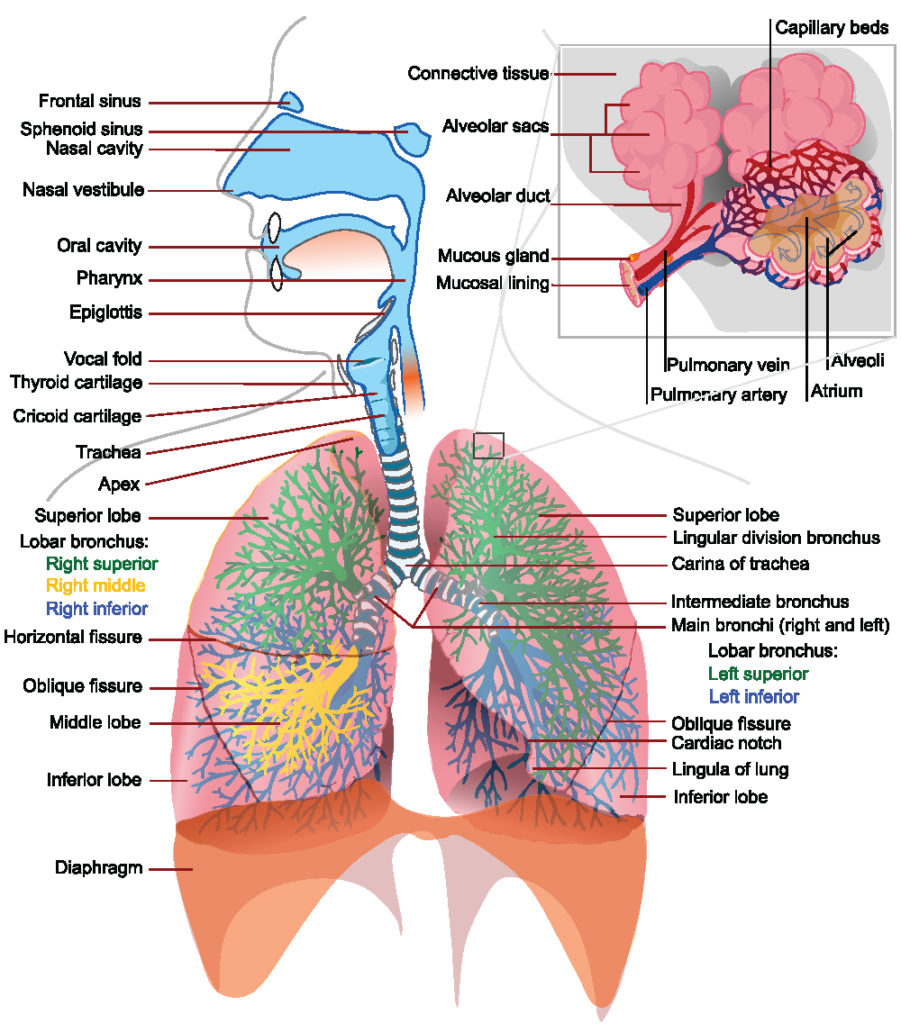

The major organs of the respiratory system function primarily to provide oxygen to body tissues for cellular respiration, remove the waste product carbon dioxide, and help to maintain acid-base balance. Portions of the respiratory system are also used for non-vital functions, such as sensing odors, speech production, and for straining, such as during childbirth or coughing.

Figure 1. The major respiratory structures span the nasal cavity to the diaphragm.

Functionally, the respiratory system can be divided into a conducting zone and a respiratory zone. The conducting zone of the respiratory system includes the organs and structures not directly involved in gas exchange. The gas exchange occurs in the respiratory zone.

Conducting Zone

The major functions of the conducting zone are to provide a route for incoming and outgoing air, remove debris and pathogens from the incoming air, and warm and humidify the incoming air. Several structures within the conducting zone perform other functions as well. The epithelium of the nasal passages, for example, is essential to sensing odors, and the bronchial epithelium that lines the lungs can metabolize some airborne carcinogens.

The Nose and its Adjacent Structures

The major entrance and exit for the respiratory system is through the nose. When discussing the nose, it is helpful to divide it into two major sections: the external nose, and the nasal cavity or internal nose.

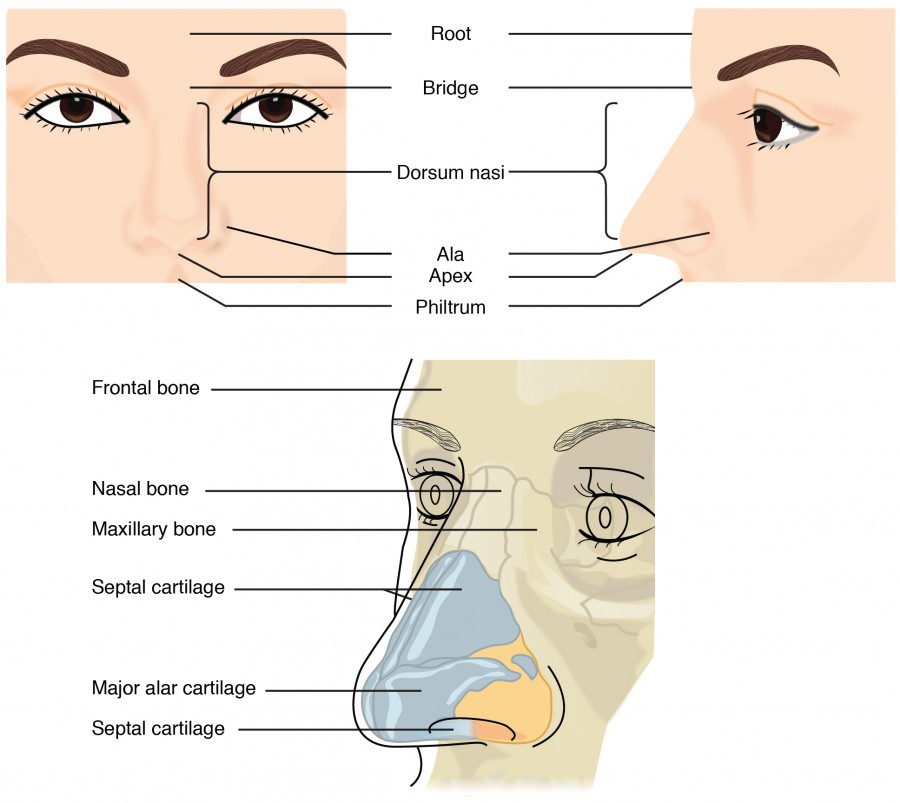

The external nose consists of the surface and skeletal structures that result in the outward appearance of the nose and contribute to its numerous functions. The root is the region of the nose located between the eyebrows. The bridge is the part of the nose that connects the root to the rest of the nose. The dorsum nasi is the length of the nose. The apex is the tip of the nose. On either side of the apex, the nostrils are formed by the alae (singular = ala). An ala is a cartilaginous structure that forms the lateral side of each naris (plural = nares), or nostril opening. The philtrum is the concave surface that connects the apex of the nose to the upper lip.

Figure 2. This illustration shows features of the external nose (top) and skeletal features of the nose (bottom).

Underneath the thin skin of the nose are its skeletal features. While the root and bridge of the nose consist of bone, the protruding portion of the nose is composed of cartilage. As a result, when looking at a skull, the nose is missing. The nasal bone is one of a pair of bones that lies under the root and bridge of the nose. The nasal bone articulates superiorly with the frontal bone and laterally with the maxillary bones. Septal cartilage is flexible hyaline cartilage connected to the nasal bone, forming the dorsum nasi. The alar cartilage consists of the apex of the nose; it surrounds the naris.

Figure 3. Upper Airway

The nares open into the nasal cavity, which is separated into left and right sections by the nasal septum. The nasal septum is formed anteriorly by a portion of the septal cartilage (the flexible portion you can touch with your fingers) and posteriorly by the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid bone (a cranial bone located just posterior to the nasal bones) and the thin vomer bones (whose name refers to its plough shape). Each lateral wall of the nasal cavity has three bony projections, called the superior, middle, and inferior nasal conchae. The inferior conchae are separate bones, whereas the superior and middle conchae are portions of the ethmoid bone. Conchae serve to increase the surface area of the nasal cavity and to disrupt the flow of air as it enters the nose, causing air to bounce along the epithelium, where it is cleaned and warmed. The conchae and meatuses also conserve water and prevent dehydration of the nasal epithelium by trapping water during exhalation. The floor of the nasal cavity is composed of the palate. The hard palate at the anterior region of the nasal cavity is composed of bone. The soft palate at the posterior portion of the nasal cavity consists of muscle tissue. Air exits the nasal cavities via the internal nares and moves into the pharynx.

Several bones that help form the walls of the nasal cavity have air-containing spaces called the paranasal sinuses, which serve to warm and humidify incoming air. Sinuses are lined with a mucosa. Each paranasal sinus is named for its associated bone: frontal sinus, maxillary sinus, sphenoidal sinus, and ethmoidal sinus. The sinuses produce mucus and lighten the weight of the skull.

The nares and anterior portion of the nasal cavities are lined with mucous membranes, containing sebaceous glands and hair follicles that serve to prevent the passage of large debris, such as dirt, through the nasal cavity. An olfactory epithelium used to detect odors is found deeper in the nasal cavity.

The conchae, meatuses, and paranasal sinuses are lined by respiratory epithelium composed of pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium. The epithelium contains goblet cells, one of the specialized, columnar epithelial cells that produce mucus to trap debris. The cilia of the respiratory epithelium help remove the mucus and debris from the nasal cavity with a constant beating motion, sweeping materials towards the throat to be swallowed. Interestingly, cold air slows the movement of the cilia, resulting in accumulation of mucus that may in turn lead to a runny nose during cold weather. This moist epithelium functions to warm and humidify incoming air. Capillaries located just beneath the nasal epithelium warm the air by convection. Serous and mucus-producing cells also secrete the lysozyme enzyme and proteins called defensins, which have antibacterial properties. Immune cells that patrol the connective tissue deep to the respiratory epithelium provide additional protection.

Figure 4. Respiratory epithelium is the pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium. Seromucous glands provide lubricating mucus. LM × 680. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

Pharynx

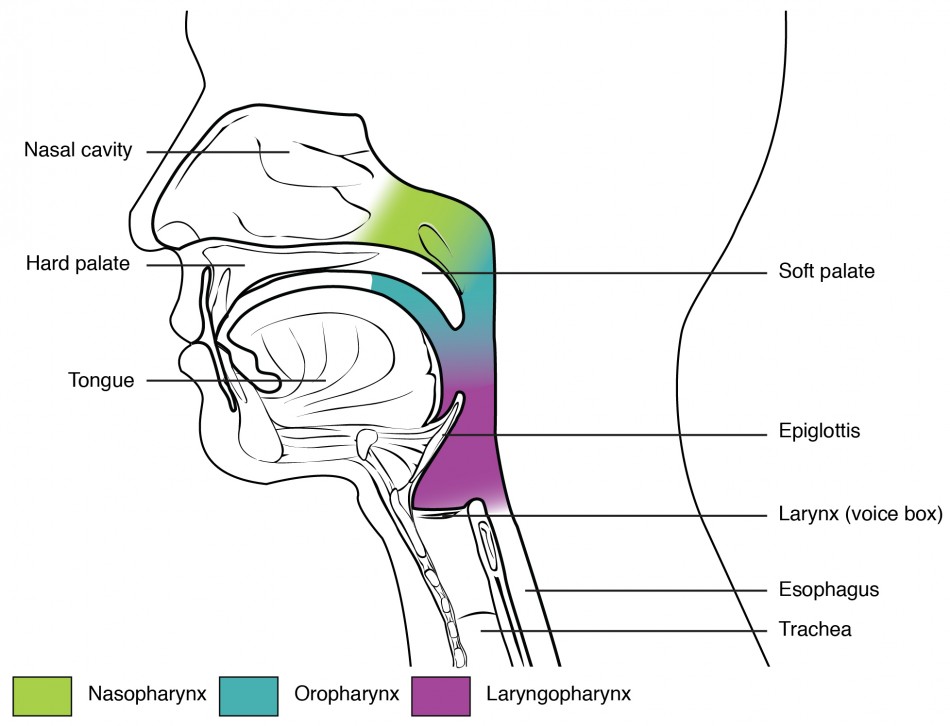

The pharynx is a tube formed by skeletal muscle and lined by mucous membrane that is continuous with that of the nasal cavities. The pharynx is divided into three major regions: the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the laryngopharynx.

Figure 5. The pharynx is divided into three regions: the nasopharynx, the oropharynx, and the laryngopharynx.

The nasopharynx is flanked by the conchae of the nasal cavity, and it serves only as an airway. At the top of the nasopharynx are the pharyngeal tonsils. A pharyngeal tonsil, also called an adenoid, is an aggregate of lymphoid reticular tissue similar to a lymph node that lies at the superior portion of the nasopharynx. The function of the pharyngeal tonsil is not well understood, but it contains a rich supply of lymphocytes and is covered with ciliated epithelium that traps and destroys invading pathogens that enter during inhalation. The pharyngeal tonsils are large in children, but interestingly, tend to regress with age and may even disappear. The uvula is a small bulbous, teardrop-shaped structure located at the apex of the soft palate. Both the uvula and soft palate move like a pendulum during swallowing, swinging upward to close off the nasopharynx to prevent ingested materials from entering the nasal cavity. In addition, auditory (Eustachian) tubes that connect to each middle ear cavity open into the nasopharynx. This connection is why colds often lead to ear infections.

The oropharynx is a passageway for both air and food. The oropharynx is bordered superiorly by the nasopharynx and anteriorly by the oral cavity. The fauces is the opening at the connection between the oral cavity and the oropharynx. As the nasopharynx becomes the oropharynx, the epithelium changes from pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium to stratified squamous epithelium. The oropharynx contains two distinct sets of tonsils, the palatine and lingual tonsils. A palatine tonsil is one of a pair of structures located laterally in the oropharynx in the area of the fauces. The lingual tonsil is located at the base of the tongue. Similar to the pharyngeal tonsil, the palatine and lingual tonsils are composed of lymphoid tissue, and trap and destroy pathogens entering the body through the oral or nasal cavities.

The laryngopharynx is inferior to the oropharynx and posterior to the larynx. It continues the route for ingested material and air until its inferior end, where the digestive and respiratory systems diverge. The stratified squamous epithelium of the oropharynx is continuous with the laryngopharynx. Anteriorly, the laryngopharynx opens into the larynx, whereas posteriorly, it enters the esophagus.

Larynx

The larynx is a cartilaginous structure inferior to the laryngopharynx that connects the pharynx to the trachea and helps regulate the volume of air that enters and leaves the lungs. The structure of the larynx is formed by several pieces of cartilage. Three large cartilage pieces—the thyroid cartilage (anterior), epiglottis (superior), and cricoid cartilage (inferior)—form the major structure of the larynx. The thyroid cartilage is the largest piece of cartilage that makes up the larynx. The thyroid cartilage consists of the laryngeal prominence, or “Adam’s apple,” which tends to be more prominent in males. The thick cricoid cartilage forms a ring, with a wide posterior region and a thinner anterior region. Three smaller, paired cartilages—the arytenoids, corniculate, and cuneiforms—attach to the epiglottis and the vocal cords and muscles that help move the vocal cords to produce speech.

Figure 6. The larynx extends from the laryngopharynx and the hyoid bone to the trachea.

Figure 7. The true vocal cords and vestibular folds of the larynx are viewed inferiorly from the laryngopharynx.

The epiglottis, attached to the thyroid cartilage, is a very flexible piece of elastic cartilage that covers the opening of the trachea. When in the “closed” position, the unattached end of the epiglottis rests on the glottis. The glottis is composed of the vestibular folds, the true vocal cords, and the space between these folds. A vestibular fold, or false vocal cord, is one of a pair of folded sections of the mucous membrane. A true vocal cord is one of the white, membranous folds attached by muscle to the thyroid and arytenoid cartilages of the larynx on their outer edges. The inner edges of the true vocal cords are free, allowing oscillation to produce sound. The size of the membranous folds of the true vocal cords differs between individuals, producing voices with different pitch ranges. Folds in males tend to be larger than those in females, which creates a deeper voice. The act of swallowing causes the pharynx and larynx to lift upward, allowing the pharynx to expand and the epiglottis of the larynx to swing downward, closing the opening to the trachea. These movements produce a larger area for food to pass through while preventing food and beverages from entering the trachea.

Continuous with the laryngopharynx, the superior portion of the larynx is lined with stratified squamous epithelium, transitioning into pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium that contains goblet cells. Similar to the nasal cavity and nasopharynx, this specialized epithelium produces mucus to trap debris and pathogens as they enter the trachea. The cilia beat the mucus upward towards the laryngopharynx, where it can be swallowed down the esophagus.

Trachea

The trachea (windpipe) extends from the larynx toward the lungs. The trachea is formed by 16 to 20 stacked, C-shaped pieces of hyaline cartilage that are connected by dense connective tissue. The trachealis muscle and elastic connective tissue together form the fibroelastic membrane, a flexible membrane that closes the posterior surface of the trachea, connecting the C-shaped cartilages. The fibroelastic membrane allows the trachea to stretch and expand slightly during inhalation and exhalation, whereas the rings of cartilage provide structural support and prevent the trachea from collapsing. In addition, the trachealis muscle can be contracted to force air through the trachea during exhalation. The trachea is lined with pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium, which is continuous with the larynx. The esophagus borders the trachea posteriorly.

Figure 8. (a) The tracheal tube is formed by stacked, C-shaped pieces of hyaline cartilage. (b) The layer visible in this cross-section of tracheal wall tissue between the hyaline cartilage and the lumen of the trachea is the mucosa, which is composed of pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium that contains goblet cells. LM × 1220. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

Bronchial Tree

The trachea branches into the right and left primary bronchi at the carina. These bronchi are also lined by pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium containing mucus-producing goblet cells. The carina is a raised structure that contains specialized nervous tissue that induces violent coughing if a foreign body, such as food, is present. Rings of cartilage, similar to those of the trachea, support the structure of the bronchi and prevent their collapse. The primary bronchi enter the lungs at the hilum, a concave region where blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, and nerves also enter the lungs. The bronchi continue to branch into the bronchial a tree. A bronchial tree (or respiratory tree) is the collective term used for these multiple-branched bronchi. The main function of the bronchi, like other conducting zone structures, is to provide a passageway for air to move into and out of each lung. In addition, the mucous membrane traps debris and pathogens.

A bronchiole branches from the tertiary bronchi. Bronchioles, which are about 1 mm in diameter, further branch until they become the tiny terminal bronchioles, which lead to the structures of gas exchange. There are more than 1000 terminal bronchioles in each lung. The muscular walls of the bronchioles do not contain cartilage-like those of the bronchi. This muscular wall can change the size of the tubing to increase or decrease airflow through the tube.

Respiratory Zone

In contrast to the conducting zone, the respiratory zone includes structures that are directly involved in gas exchange. The respiratory zone begins where the terminal bronchioles join a respiratory bronchiole, the smallest type of bronchiole, which then leads to an alveolar duct, opening into a cluster of alveoli.

Figure 9. Bronchioles lead to alveolar sacs in the respiratory zone, where gas exchange occurs.

Alveoli

An alveolar duct is a tube composed of smooth muscle and connective tissue, which opens into a cluster of alveoli. An alveolus is one of the many small, grape-like sacs that are attached to the alveolar ducts.

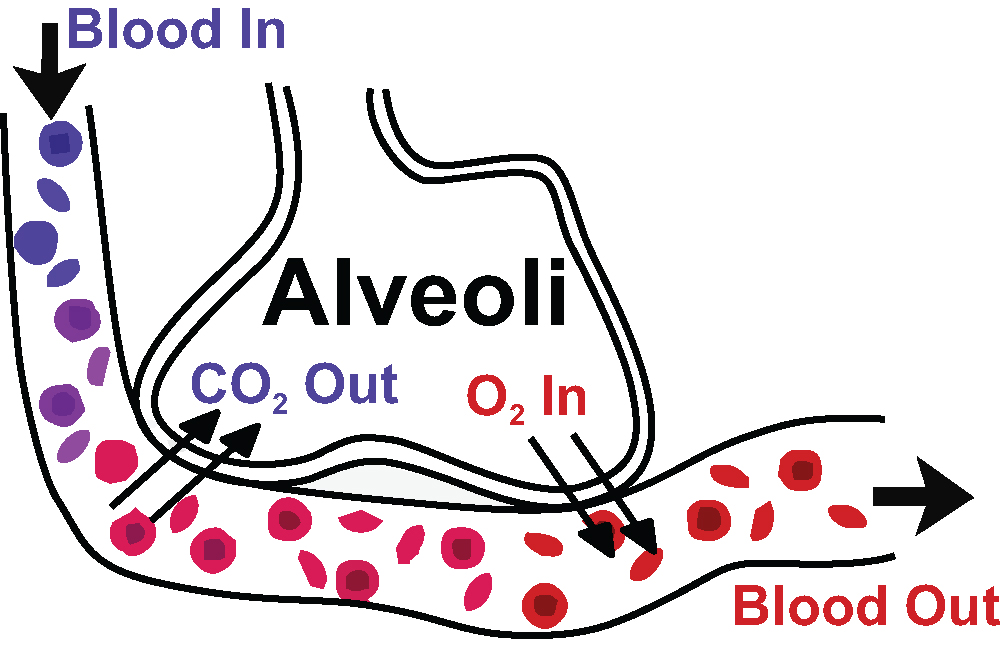

An alveolar sac is a cluster of many individual alveoli that are responsible for gas exchange. An alveolus is approximately 200 mm in diameter with elastic walls that allow the alveolus to stretch during air intake, which greatly increases the surface area available for gas exchange. Alveoli are connected to their neighbors by alveolar pores, which help maintain equal air pressure throughout the alveoli and lung.

Figure 10. (a) The alveolus is responsible for gas exchange. (b) A micrograph shows the alveolar structures within lung tissue. LM × 178. (Micrograph provided by the Regents of University of Michigan Medical School © 2012)

The alveolar wall consists of three major cell types: type I alveolar cells, type II alveolar cells, and alveolar macrophages. A type I alveolar cell is a squamous epithelial cell of the alveoli, which constitutes up to 97 percent of the alveolar surface area. These cells are about 25 nm thick and are highly permeable to gases. A type II alveolar cell is interspersed among the type I cells and secretes pulmonary surfactant, a substance composed of phospholipids and proteins that reduces the surface tension of the alveoli. Roaming around the alveolar wall is the alveolar macrophage, a phagocytic cell of the immune system that removes debris and pathogens that have reached the alveoli.

The simple squamous epithelium formed by type I alveolar cells is attached to a thin, elastic basement membrane. This epithelium is extremely thin and borders the endothelial membrane of capillaries. Taken together, the alveoli and capillary membranes form a respiratory membrane that is approximately 0.5 mm thick. The respiratory membrane allows gases to cross by simple diffusion, allowing oxygen to be picked up by the blood for transport and CO2 to be released into the air of the alveoli.

DISEASES OF THE RESPIRATORY SYSTEM: ASTHMA

Asthma is a common condition that affects the lungs in both adults and children. Approximately 8.2 percent of adults (18.7 million) and 9.4 percent of children (7 million) in the United States suffer from asthma. In addition, asthma is the most frequent cause of hospitalization in children.

Asthma is a chronic disease characterized by inflammation and edema of the airway, and bronchospasms (that is, constriction of the bronchioles), which can inhibit air from entering the lungs. In addition, excessive mucus secretion can occur, which further contributes to airway occlusion. Cells of the immune system, such as eosinophils and mononuclear cells, may also be involved in infiltrating the walls of the bronchi and bronchioles.

Bronchospasms occur periodically and lead to an “asthma attack.” An attack may be triggered by environmental factors such as dust, pollen, pet hair, or dander, changes in the weather, mold, tobacco smoke, and respiratory infections, or by exercise and stress.

Figure 11. (a) Normal lung tissue does not have the characteristics of lung tissue during (b) an asthma attack, which include thickened mucosa, increased mucus-producing goblet cells, and eosinophil infiltrates.

Symptoms of an asthma attack involve coughing, shortness of breath, wheezing, and tightness of the chest. Symptoms of a severe asthma attack that requires immediate medical attention would include difficulty breathing that results in blue (cyanotic) lips or face, confusion, drowsiness, a rapid pulse, sweating, and severe anxiety. The severity of the condition, frequency of attacks, and identified triggers influence the type of medication that an individual may require. Longer-term treatments are used for those with more severe asthma. Short-term, fast-acting drugs that are used to treat an asthma attack are typically administered via an inhaler. For young children or individuals who have difficulty using an inhaler, asthma medications can be administered via a nebulizer.

In many cases, the underlying cause of the condition is unknown. However, recent research has demonstrated that certain viruses, such as human rhinovirus C (HRVC), and the bacteria Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydia pneumoniae that are contracted in infancy or early childhood, may contribute to the development of many cases of asthma.

PRACTICE QUESTION

Watch this video to learn more about what happens during an asthma attack. What are the three changes that occur inside the airways during an asthma attack?

Show Answer

Chapter Review

The respiratory system is responsible for obtaining oxygen and getting rid of carbon dioxide and aiding in speech production and in sensing odors. From a functional perspective, the respiratory system can be divided into two major areas: the conducting zone and the respiratory zone. The conducting zone consists of all of the structures that provide passageways for air to travel into and out of the lungs: the nasal cavity, pharynx, trachea, bronchi, and most bronchioles. The nasal passages contain the conchae and meatuses that expand the surface area of the cavity, which helps to warm and humidify incoming air, while removing debris and pathogens. The pharynx is composed of three major sections: the nasopharynx, which is continuous with the nasal cavity; the oropharynx, which borders the nasopharynx and the oral cavity; and the laryngopharynx, which borders the oropharynx, trachea, and esophagus. The respiratory zone includes the structures of the lung that are directly involved in gas exchange: the terminal bronchioles and alveoli.

The lining of the conducting zone is composed mostly of pseudostratified ciliated columnar epithelium with goblet cells. The mucus traps pathogens and debris, whereas beating cilia move the mucus superiorly toward the throat, where it is swallowed. As the bronchioles become smaller and smaller, and nearer the alveoli, the epithelium thins and is simple squamous epithelium in the alveoli. The endothelium of the surrounding capillaries, together with the alveolar epithelium, forms the respiratory membrane. This is a blood-air barrier through which gas exchange occurs by simple diffusion.

Self Check

Answer the question(s) below to see how well you understand the topics covered in the previous section.

CRITICAL THINKING QUESTIONS

- Describe the three regions of the pharynx and their functions.

- If a person sustains an injury to the epiglottis, what would be the physiological result?

- Compare and contrast the conducting and respiratory zones.

Glossary

ala: (plural = alae) small, flaring structure of a nostril that forms the lateral side of the nares

alar cartilage: cartilage that supports the apex of the nose and helps shape the nares; it is connected to the septal cartilage and connective tissue of the alae

alveolar duct: small tube that leads from the terminal bronchiole to the respiratory bronchiole and is the point of attachment for alveoli

alveolar macrophage: immune system cell of the alveolus that removes debris and pathogens

alveolar pore: opening that allows airflow between neighboring alveoli

alveolar sac: cluster of alveoli

alveolus: small, grape-like sac that performs gas exchange in the lungs

apex: tip of the external nose

bronchial tree: collective name for the multiple branches of the bronchi and bronchioles of the respiratory system

bridge: portion of the external nose that lies in the area of the nasal bones

bronchiole: branch of bronchi that are 1 mm or less in diameter and terminate at alveolar sacs

bronchus: tube connected to the trachea that branches into many subsidiaries and provides a passageway for air to enter and leave the lungs

conducting zone: region of the respiratory system that includes the organs and structures that provide passageways for air and are not directly involved in gas exchange

cricoid cartilage: portion of the larynx composed of a ring of cartilage with a wide posterior region and a thinner anterior region; attached to the esophagus

dorsum nasi: intermediate portion of the external nose that connects the bridge to the apex and is supported by the nasal bone

epiglottis: leaf-shaped piece of elastic cartilage that is a portion of the larynx that swings to close the trachea during swallowing

external nose: region of the nose that is easily visible to others

fauces: portion of the posterior oral cavity that connects the oral cavity to the oropharynx

fibroelastic membrane: specialized membrane that connects the ends of the C-shape cartilage in the trachea; contains smooth muscle fibers

glottis: opening between the vocal folds through which air passes when producing speech

laryngeal prominence: region where the two lamina of the thyroid cartilage join, forming a protrusion known as “Adam’s apple”

laryngopharynx: portion of the pharynx bordered by the oropharynx superiorly and esophagus and trachea inferiorly; serves as a route for both air and food

larynx: cartilaginous structure that produces the voice, prevents food and beverages from entering the trachea, and regulates the volume of air that enters and leaves the lungs

lingual tonsil: lymphoid tissue located at the base of the tongue

meatus: one of three recesses (superior, middle, and inferior) in the nasal cavity attached to the conchae that increase the surface area of the nasal cavity

naris: (plural = nares) opening of the nostrils

nasal bone: bone of the skull that lies under the root and bridge of the nose and is connected to the frontal and maxillary bones

nasal septum: wall composed of bone and cartilage that separates the left and right nasal cavities

nasopharynx: portion of the pharynx flanked by the conchae and oropharynx that serves as an airway

oropharynx: portion of the pharynx flanked by the nasopharynx, oral cavity, and laryngopharynx that is a passageway for both air and food

palatine tonsil: one of the paired structures composed of lymphoid tissue located anterior to the uvula at the roof of isthmus of the fauces

paranasal sinus: one of the cavities within the skull that is connected to the conchae that serve to warm and humidify incoming air, produce mucus, and lighten the weight of the skull; consists of frontal, maxillary, sphenoidal, and ethmoidal sinuses

pharyngeal tonsil: structure composed of lymphoid tissue located in the nasopharynx

pharynx: region of the conducting zone that forms a tube of skeletal muscle lined with respiratory epithelium; located between the nasal conchae and the esophagus and trachea

philtrum: concave surface of the face that connects the apex of the nose to the top lip

pulmonary surfactant: substance composed of phospholipids and proteins that reduces the surface tension of the alveoli; made by type II alveolar cells

respiratory bronchiole: specific type of bronchiole that leads to alveolar sacs

respiratory epithelium: ciliated lining of much of the conducting zone that is specialized to remove debris and pathogens, and produce mucus

respiratory membrane: alveolar and capillary wall together, which form an air-blood barrier that facilitates the simple diffusion of gases

respiratory zone: includes structures of the respiratory system that are directly involved in gas exchange

root: region of the external nose between the eyebrows

thyroid cartilage: largest piece of cartilage that makes up the larynx and consists of two lamina

trachea: tube composed of cartilaginous rings and supporting tissue that connects the lung bronchi and the larynx; provides a route for air to enter and exit the lung

trachealis muscle: smooth muscle located in the fibroelastic membrane of the trachea

true vocal cord: one of the pair of folded, white membranes that have a free inner edge that oscillates as air passes through to produce sound

type I alveolar cell: squamous epithelial cells that are the major cell type in the alveolar wall; highly permeable to gases

type II alveolar cell: cuboidal epithelial cells that are the minor cell type in the alveolar wall; secrete pulmonary surfactant

vestibular fold: part of the folded region of the glottis composed of mucous membrane; supports the epiglottis during swallowing

References

, or from a loss of elastic recoil of the lungs.

, or from a loss of elastic recoil of the lungs.