Hormone Secretion/Hormones are secreted from the glands of the endocrine system, they are specific in that each hormone causes a response in a specific target organ or group of cells, rather than on the body as a whole. Exocrine hormones are secreted via a duct into the blood and usually affect a distant organ or tissue hormone secretion in birds is inhibited by peripheral hormones. If GH is acting via IGF-I, then negative feedback by IGF-I on GH release would seem to be likely. IGF-I has been found to inhibit GH release in vitro and in vivo in chicks (Perez et al., 1985; Buonomo et al., 1987). Similarly, as GH increases the circulating concentration of the active thyroid hormone, T3, then it is probable that T3 would inhibit GH secretion. This is the case. The presence of elevated levels of T3 reduces GH release from the chicken pituitary gland in vivo (e.g. Scanes and Harvey, 1987b) and in vitro (Donoghue and Scanes, 1991).

Control of Hormone Secretion

A hormone is a molecule released by a cell or a gland in one part of the body that exerts effects via specific receptors at other sites.

Key Points

The endocrine system relies on feedback mechanisms to control the hormone levels in the circulatory system.

Negative feedback systems prevent deviation from an ideal mean to maintain homeostasis.

Positive feedback systems facilitate deviation from the mean.

Key Terms

negative feedback: A system that prevents deviation from a mean value.

positive feedback: A system that promotes deviation from a mean value.

The physiological activity of a hormone depends largely on its concentration within the circulatory system. The effects of too high or too low a concentration of hormones can be damaging—this level must be tightly controlled.

The endocrine system relies on feedback systems to regulate hormone production and secretion.

Negative Feedback

Most endocrine glands are under negative feedback control that acts to maintain homeostasis, i.e., prevent deviation from an ideal value. A key example of a negative feedback system is the regulation of the thyroid hormone thyroxine, which regulates numerous key metabolic processes.

Briefly, neurons in the hypothalamus secrete a thyroid-releasing hormone that stimulates cells in the anterior pituitary to secrete thyroid-stimulating hormone. The thyroid-stimulating hormone then stimulates the release of thyroxine from the thyroid gland.

When the blood concentration of thyroxine rises above the ideal value as detected by sensory neurons, the hypothalamus is signaled to stop thyroid-releasing hormone production, which eventually lowers the levels of thyroxine in the blood. When these drop below the ideal value the hypothalamus is signaled to begin secreting thyroid-releasing hormone again.

Positive Feedback

Positive feedback mechanisms control self-perpetuating events, that is, they encourage deviation from the mean. Positive feedback systems are much less common although they do exist. A key example occurs during childbirth.

The hormone oxytocin is produced by the posterior pituitary that stimulates and enhances contractions during labor. During birth, as the baby moves through the birth canal, pressure receptors within the cervix signal the hypothalamus to stimulate the pituitary to secrete oxytocin.

Oxytocin travels to the uterus through the bloodstream, stimulating the muscles in the uterine wall to contract which in turn increases the activation of the pressure receptors and stimulates the further release of oxytocin. The strength of muscle contractions intensifies until the baby is born and the stimulation of the pressure receptors is removed, which stops the release of oxytocin.

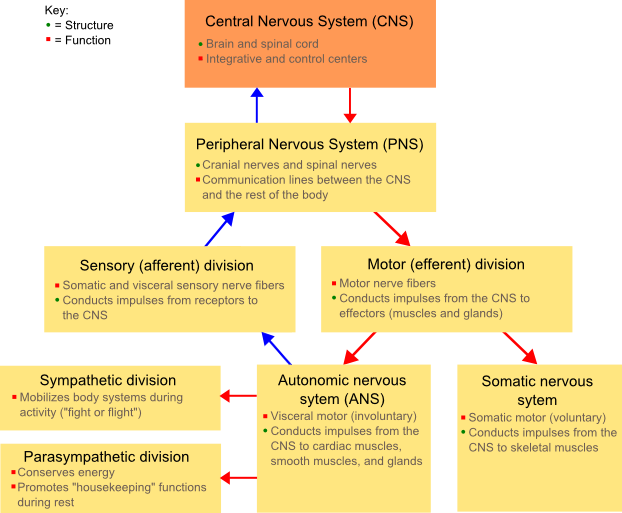

The Endocrine system (along with the nervous system) controls and regulates the complex activities of the body. The Endocrine system regulates the activities of the body by secreting complex chemical substances (hormones) into the bloodstream. These secretions come from a variety of glands that control various organs of the body. The key functions are:

- To regulate the metabolic functions of the body.

- To regulate the rate of chemical reactions in various cells.

- To influence the ability of substances to transport themselves through cell membranes.

About Hormones

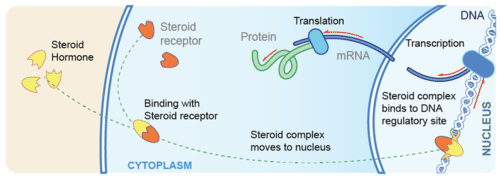

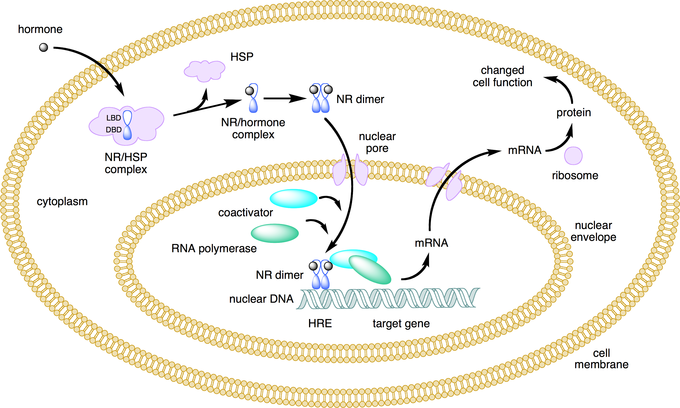

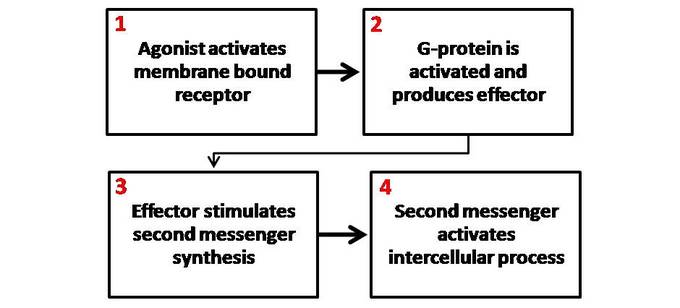

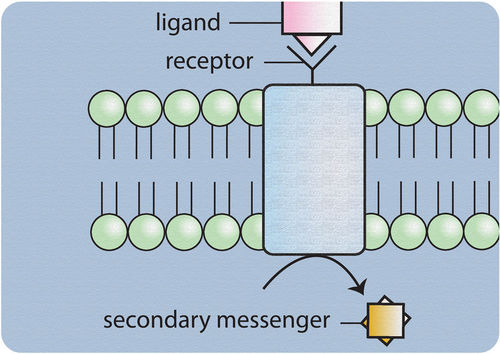

- Hormones are secreted from the glands of the endocrine system, they are specific in that each hormone causes a response in a specific target organ or group of cells, rather than on the body as a whole. Exocrine hormones are secreted via a duct into the blood and usually affect a distant organ or tissue. Endocrine hormones are secreted within the tissue (rather than via a duct) and enter the bloodstream via capillaries.

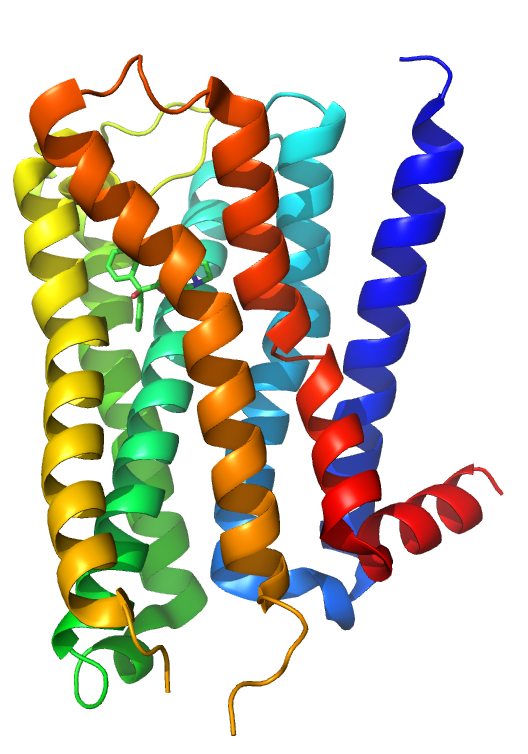

Hormones can be grouped into three main types

- amines, these are simple molecules

-

- proteins and peptides which are made from chains of amino acids

- steroids which are derived from cholesterol.

- Glands – discharge hormones directly into the bloodstream. They have built-in feedback mechanisms that maintain a proper balance of hormones, and prevent excess hormone secretion. Low concentrations of a hormone will often trigger the gland to secrete. Once the concentrations of the hormone in the blood rise this may cause the gland to stop secreting until once again hormone concentrations fall. This feedback mechanism (which is characteristic of most glands) causes a cycle of hormone secretions.

- Disposal of waste – Once hormones have served their function on their target organs/tissues they are destroyed. They are either destroyed by the liver or the actual tissues of the target organs. They are then removed by the kidneys.

The Pituitary Gland

This is known as the “master gland” because it exerts control over all of the other glands of the endocrine system. Despite its importance, the pituitary gland is no larger than a small pea. The Pituitary gland is made up of two separate glands: the Anterior lobe which is an outgrowth of the pharynx, and the

- The posterior lobe is an outgrowth of the brain composed of neural (nerve) tissue.

- The Anterior Lobe of the pituitary plays the ‘master’ role secreting six major hormones that affect most of the body, including the other Endocrine glands:

- ACTH (Adrenocorticotrophic hormone) stimulates the adrenal glands to secrete their hormones.

- HGH (Human growth hormone) also known as the somatotrophic hormone is responsible for the growth of long bones, muscles, and viscera.

- TSH (Thyroid-stimulating hormone) influences the structure of the thyroid and causes it to secrete thyroid hormone.

- FSH (Follicle-stimulating hormone) stimulates female egg production or male sperm production.

- PRL (Prolactin) in females causes the corpus luteum the area around the mature follicle to produce two important hormones: Oestrogen and Progesterone. During pregnancy, PRL is also responsible for the development of the glandular tissues of the breast which produce milk.

- LH (Luteinizing hormone) works in conjunction with FSH in females to cause ovulation and prepares the uterus for pregnancy, in males the testes to secrete testosterone.

- The Posterior Lobe of the Pituitary Gland (or neurohypophysis) stores and releases hormones secreted by the hypothalamus section of the brain including:

- ADH (Antidiuretic hormone) stimulates the smooth muscles, blood vessels, and intestine. ADH increases the kidney’s permeability to water allowing the body to re-absorb water that would otherwise escape in urine.

- OT (Oxytocin) stimulates the smooth muscles of the uterus during pregnancy, causing it to contract during labor. It also stimulates the lacteals (milk ducts) in the breast.

The Thyroid gland

The thyroid is a butterfly-shaped gland which is located at the base of the throat. It has two lobes separated in the middle by a strip of tissue (the isthmus). The Thyroid itself secretes three main hormones:

- Thyroxine contains iodine which is essential for the body’s normal growth and metabolism. Thyroxine helps control body size, regulating not only the growth of tissues but also the differentiation or specialization of tissues.

- Triiodothyronine has similar functions to thyroxine.

- Calcitonin causes a decrease in the concentration of calcium in the blood. Calcitonin works with secretions from the parathyroid glands to maintain the balance of calcium necessary for the body to function.

People who have surgery to remove the thyroid gland (thyroidectomy) for cancer or other thyroid problems usually need to take thyroxine supplements in order to maintain normal weight and body functions.

The Parathyroids

There are four Parathyroid glands which are small and rounded, arranged in two pairs usually located above and below the thyroid. Each Parathyroid is small, yellow, and smooth, sometimes they imbed themselves in the thyroid itself.

Parathyroid hormone increases the blood concentrations of calcium and phosphorous, working to balance the Calcitonin which is secreted by the thyroid to maintain the body’s balance of calcium.

The Pancreas

The pancreas is a long, narrow, lobed gland located behind the stomach. The Pancreas has two types of cells: exocrine and endocrine cells. The exocrine cells secrete Pancreatic juices which are used in the duodenum as an important part in the digestive system. The endocrine cells are arranged in clusters throughout the Pancreas, these known as Islets of Langerhans. There are three types of endocrine cells; alpha cells which secrete glucagon, beta cells which secrete insulin, and delta cells which inhibit the secretion of glucagon and insulin:

- Glucagon increases the blood glucose level by stimulating the liver causing convert Glycogen into Glucose (sugar).

- Insulin increases the permeability of the cell to glucose, which the cells use for energy. By promoting the utilization of glucose by the tissue cells, insulin causes a decrease in the concentration of glucose in the blood. Insulin also promotes the storage of glycogen in the liver.

The Adrenal Glands

The adrenal glands resemble small caps perched on top of each kidney. The Adrenal is actually a combination of two glands the adrenal cortex and the adrenal medulla.

- The adrenal cortex is essential for life, as opposed to the adrenal medulla which is important but not indispensable. The anterior pituitary controls the adrenal cortex by secreting the hormone ACTH. All of the secretions of the adrenal cortex are known as steroids, many of which can now be manufactured synthetically. The adrenal cortex is made up of three layers associated with three classes of hormones:

- Mineralocorticoids are produced by the outer layer of the adrenal cortex, the most important of which is aldosterone. Aldosterone promotes the retention of sodium (Na+) and the excretion of potassium (K+). This helps to maintain both the electrolyte and water content of the body.

- Glucocorticoids are produced by the middle cortex. These affect almost every cell in the body regulating the metabolism of fats, proteins, and carbohydrates. Cortisone is one such glucocorticoid.

- Gonadal hormones are produced by the inner cortex, there are roughly even amounts of two types of hormones secreted: Androgen (male) and Estrogen (female). The adrenal gland is not the only gland to secrete sex hormones.

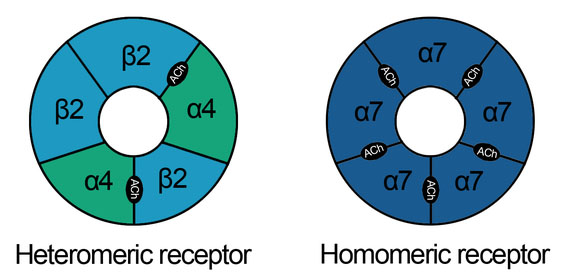

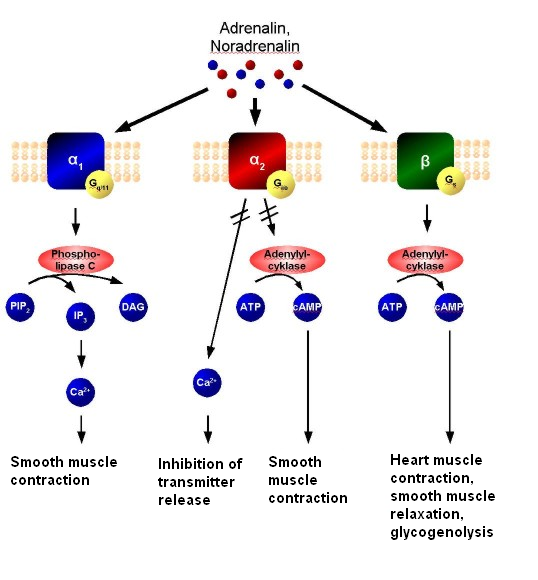

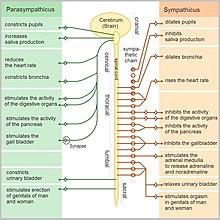

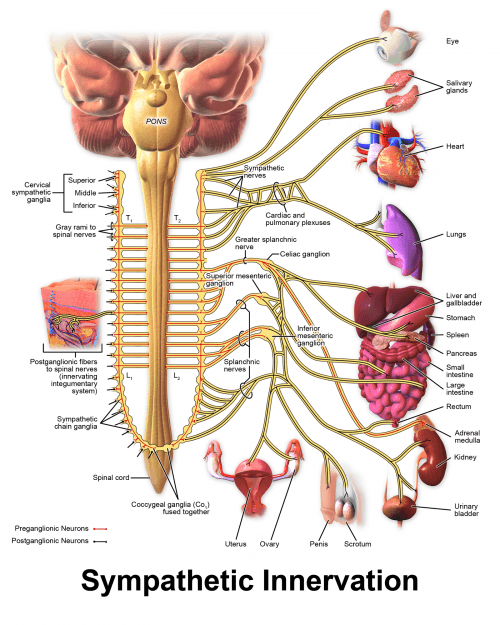

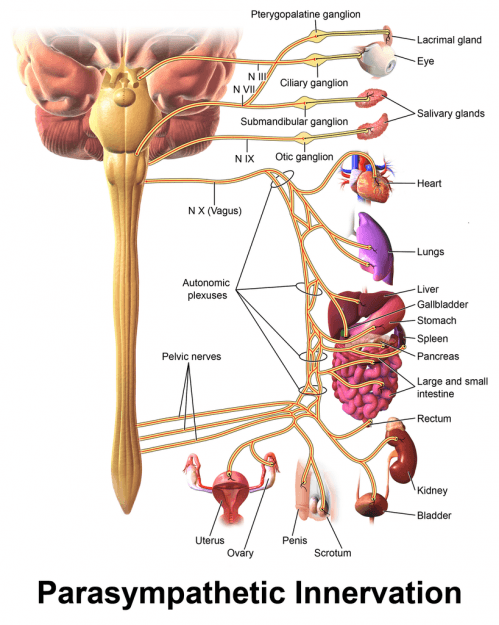

- The Adrenal Medulla is the inner part of the adrenal gland. The hormones secreted affect the structures in the body that are under the control of the sympathetic nervous system, aiding the body to deal with stressful situations such as fright, attack or pursuit. They are both associated with an increased heartbeat, higher blood pressure, and higher blood glucose levels, thus preparing the body for quick action.

- Adrenalin (or epinephrine) affects both alpha and beta receptors in the nervous system.

- Noradrenalin (Norepinephrine) affects only the alpha receptors of the nervous system.

The Gonads

The gonads consist of ovaries in the female and testes in the male. These glands produce hormones important in the development and functioning of the reproductive organs. they are under the control of the pituitary gland and produce secondary sexual traits.

- Male testes are egg-shaped glands located in the sac-like scrotum, and serve two main functions: (i) The production of sperm cells, and (ii) The secretion of testosterone. Testosterone is the masculizing hormone inducing male secondary sexual characteristics after puberty.

- Female ovaries are two almond-shaped glands on each side of the uterus. They have three main functions; (i) Containing immature ova (eggs), (ii) secretion of estrogen and (ii) secretion of progesterone.

- Estrogen is secreted by the adrenal cortex as well as the ovaries and is present in the blood of all females from puberty through to menopause. estrogen acts on the structure of the reproductive organs, especially during the menstrual cycle. This induces and maintains female secondary sexual characteristics. Progesterone works on the uterus to prepare it for the implantation of a fertilized ovum (egg). It causes the development of the breasts and is essential for the complete development of the maternal proportion of the placenta.

- Giantism too much HGH is secreted before puberty.

- Dwarfism is caused by a lack of HGH before puberty.

- Diabetes Mellitus is a condition with under-secretion of insulin, causing the cells to lose their permeability to glucose preventing them from getting sugar needed for energy. Sugar remains in the blood and often the body will try and remove this leading to high sugar content in the urine, causing polyuria (passing of large volumes of urine) and polydipsia (excessive thirst).

Roots, suffixes, and prefixes

Most medical terms are comprised of a root word plus a suffix (word ending) and/or a prefix (beginning of the word). Here are some examples related to the Endocrine System.

| component | meaning | example |

| A-, AN- | without, lack | muscular atrophy = ‘wasting away’ of muscles |

| ADEN- | gland | adenoma = tumor with gland-like structure |

| END-, Endo- | within | endocrine = secreting within |

| EXO- | away from | exocrine = secreting outwardly or away from |

| GLYCO-, GLUCO- | sugar, sweet | hyperglycemia = excessive blood sugar levels |

| PARA- | near, beside | parathyroid = beside the thyroid |

| POLY- | much, many | polyadenitis = inflammation of many glands |

| THYROID- | thyroid | hypoplasia = defective growth of the thyroid |

| -CRIME | to secrete | endocrine = endo (within) crime (secrete) |

| -TROPHY | growth | hypertrophy = excessive growth of an organ or part |

| -MAGALY | enlargement | hepatomegaly = enlarged liver with hepatitis |

| -PHYSIS | growth | a growth or outcropping (as opposed to a trophy where something is physically growing) |

References