Osteosarcoma and UPS of Bone/Osteosarcoma occurs predominantly in adolescents and young adults. Review of data from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program resulted in an estimated osteosarcoma incidence rate of 4.4 cases per 1 million each year in people aged 0 to 24 years.[rx] The U.S. Census Bureau estimated that there were 110 million people in this age range in the year 2010, resulting in an incidence of roughly 450 cases per year in children and young adults younger than 25 years.

In 2013, the World Health Organization (WHO) published an update to the Classification of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone.[rx] They removed the term malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) and replaced it with undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS). This type of sarcoma is much more common in soft tissues; however, it does arise in bone. In bone, it has features that are histologically similar to osteosarcoma but it does not produce osteoid. Most of the literature describing the clinical behavior and response to therapy for this histology in bone was published before the 2013 WHO update, and a search for UPS of bone will not retrieve these articles. The citations in this summary appear with their titles as published; therefore, many references will describe MFH of bone, a condition now called UPS of bone.

Osteosarcoma accounts for approximately 5% of childhood tumors. In children and adolescents, more than 50% of these tumors arise from the long bones around the knee. Osteosarcoma is rarely observed in soft tissue or visceral organs. There appears to be no difference in presenting symptoms, tumor location, and outcome for younger patients (<12 years) compared with adolescents.[rx,rx]

Two trials conducted in the 1980s were designed to determine whether chemotherapy altered the natural history of osteosarcoma after surgical removal of the primary tumor. The outcome of patients in these trials who were treated with surgical removal of the primary tumor recapitulated the historical experience before 1970; more than one-half of these patients developed metastases within 6 months of diagnosis, and overall, approximately 90% developed recurrent disease within 2 years of diagnosis.[rx] Overall survival (OS) for patients treated with surgery alone was statistically inferior.[rx] The natural history of osteosarcoma has not changed over time, and fewer than 20% of patients with localized resectable primary tumors treated with surgery alone can be expected to survive free of relapse.[rx,rx]; [rx][Level of evidence: 1iiA]

Diagnostic Evaluation

Osteosarcoma can be diagnosed by core needle biopsy or open surgical biopsy. It is preferable that the biopsy be performed by a surgeon skilled in the techniques of limb sparing (removal of the malignant bone tumor without amputation and replacement of bones or joints with allografts or prosthetic devices). In these cases, the original biopsy incision placement is crucial. Inappropriate alignment of the biopsy or inadvertent contamination of soft tissues can render subsequent limb-preserving reconstructive surgery impossible.

Prognostic Factors

In general, prognostic factors for osteosarcoma have not been helpful in identifying patients who might benefit from treatment intensification or who might require less therapy while maintaining an excellent outcome.

Factors that influence outcome include the following:[rx]

- Primary tumor site.

- Size of the primary tumor.

- Presence of clinically detectable metastatic disease.

- Age and sex.

- Surgical resectability of the primary tumor.

- Degree of tumor necrosis after administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

Primary tumor site

The site of the primary tumor is a significant prognostic factor for patients with localized disease. Among extremity tumors, distal sites have a more favorable prognosis than do proximal sites. Axial skeleton primary tumors are associated with the greatest risk of progression and death, primarily related to the inability to achieve a complete surgical resection.

Prognostic considerations for the axial skeleton and extraskeletal sites are as follows:

- Pelvis – Pelvic osteosarcomas make up 7% to 9% of all osteosarcomas; survival rates for patients with pelvic primary tumors are 20% to 47%.[rx–rx] Complete surgical resection is associated with a positive outcome for osteosarcoma of the pelvis in some cohorts of patients.[rx,rx]

- Craniofacial/head and neck – In patients with craniofacial osteosarcoma, those with primary sites in the mandible and maxilla have a better prognosis than do patients with other primary sites in the head and neck.[rx–rx] For patients with osteosarcoma of craniofacial bones, complete resection of the primary tumor with negative margins is essential for cure.[rx–rx] When treated with surgery alone, patients who have osteosarcoma of the head and neck have a better prognosis than do those who have appendicular lesions.

- Despite a relatively high rate of inferior necrosis after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, fewer patients with craniofacial primaries develop systemic metastases than do patients with osteosarcoma originating in the extremities.[rx–rx]

- A meta-analysis concluded that systemic adjuvant chemotherapy improves the prognosis for patients with osteosarcoma of the head and neck, while small series have not shown a benefit for using adjuvant chemotherapy in these patients.[rx–rx] Another large meta-analysis detected no benefit of chemotherapy for patients with osteosarcoma of the head and neck, but suggested that incorporating chemotherapy into the treatment plan for patients with high-grade tumors may improve survival.[rx] A retrospective analysis identified a trend toward better survival in patients with high-grade osteosarcoma of the mandible and maxilla who received adjuvant chemotherapy.[rx,rx]

- Radiation therapy was found to improve local control, disease-specific survival, and OS in a retrospective study of patients with osteosarcoma of the craniofacial bones who had positive or uncertain margins after surgical resection.[rx][Level of evidence: 3iiA] Radiation-associated craniofacial osteosarcomas are generally high-grade lesions, usually fibroblastic, and tend to recur locally with a high rate of metastasis.[rx]

- Extraskeletal: Osteosarcoma in extraskeletal sites is rare in children and young adults. With current combined-modality therapy, the outcome of patients with extraskeletal osteosarcoma appears to be similar to that of patients with primary tumors of bone.[rx]

Size of the primary tumor

In some series, patients with larger tumors appeared to have a worse prognosis than did patients with smaller tumors.[ez,rx,rx] Tumor size has been assessed by longest single dimension, cross-sectional area, or estimate of tumor volume; all assessments have correlated with outcome.

Serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), which also correlates with outcome, is a likely surrogate for tumor volume.

Presence of clinically detectable metastatic disease

Patients with localized disease have a much better prognosis than do patients with overt metastatic disease. As many as 20% of patients will have radiographically detectable metastases at diagnosis, with the lung being the most common site.[rx] The prognosis for patients with metastatic disease appears to be determined largely by site(s) of metastases, number of metastases, and surgical resectability of the metastatic disease.[rx]

- Site of metastases: Prognosis appears more favorable for patients with fewer pulmonary nodules and for those with unilateral rather than bilateral pulmonary metastases;[rx] not all patients with suspected pulmonary metastases at diagnosis have osteosarcoma confirmed at the time of lung resection. In one large series, approximately 25% of patients had exclusively benign lesions removed at the time of surgery.[rx]

- A number of metastases: Patients with skip metastases (at least two discontinuous lesions in the same bone) have been reported to have inferior prognoses.[rx] However, an analysis of the German Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study experience suggests that skip lesions in the same bone do not confer an inferior prognosis if they are included in planned surgical resection. Skip metastasis in a bone other than the primary bone should be considered systemic metastasis.[rx]

- Historically, metastasis across – a joint was referred to as a skip lesion. Skip lesions across a joint might be considered hematogenous spread and have a worse prognosis.[rx]

- Patients with multifocal osteosarcoma – (defined as multiple bone lesions without a clear primary tumor) have an extremely poor prognosis.[rx,rx]

- Surgical resectability of metastases: Patients who have complete surgical ablation of the primary and metastatic tumor (when confined to the lung) after chemotherapy may attain long-term survival, although overall event-free survival (EFS) rates remain about 20% to 30% for patients with metastatic disease at diagnosis.[rx,rx,rx,rx]

Age and sex

Patients in the older adolescent and young adult age group, typically defined as age 18 to 40 years, tend to have a worse prognosis. In addition, male sex has been associated with a worse prognosis.[rx,rx,rx] Compared with the other prognostic factors listed, both age and sex have a relatively minor impact on outcome.

Surgical resectability of primary tumor

The Resectability of the tumor is a critical prognostic feature because osteosarcoma is relatively resistant to radiation therapy. Complete resection of the primary tumor and any skip lesions with adequate margins is generally considered essential for cure. A retrospective review of patients with craniofacial osteosarcoma performed by the cooperative German-Austrian-Swiss osteosarcoma study group reported that incomplete surgical resection was associated with inferior survival probability.[rx] In a European cooperative study, the size of the margin was not significant. However, the prognosis was better when both the biopsy and resection were performed at a center with orthopedic oncology experience.[rx]

For patients with axial skeletal primaries who either do not undergo surgery for their primary tumor or who undergo surgery that results in positive margins, radiation therapy may improve survival.[rx,rx]

Degree of tumor necrosis after administration of neoadjuvant chemotherapy

Most treatment protocols for osteosarcoma use an initial period of systemic chemotherapy before definitive resection of the primary tumor (or resection of sites of metastases). The pathologist assesses necrosis in the resected tumor. Patients with at least 90% necrosis in the primary tumor after induction chemotherapy have a better prognosis than do patients with less necrosis.[rx] Patients with less necrosis (<90%) in the primary tumor after initial chemotherapy have a higher rate of recurrence within the first 2 years than do patients with a more favorable amount of necrosis (≥90%).[rx]

Less necrosis should not be interpreted to mean that chemotherapy has been ineffective; cure rates for patients with little or no necrosis after induction chemotherapy are much higher than cure rates for patients who receive no chemotherapy. A review of two consecutive prospective trials performed by the Children’s Oncology Group showed that histologic necrosis in the primary tumor after initial chemotherapy was affected by the duration and intensity of the initial period of chemotherapy. More necrosis was associated with better outcome in both trials, but the magnitude of the difference between patients with more and less necrosis was diminished with a longer and more intensive period of initial chemotherapy.[44][Level of evidence: 1iiD]

Additional possible prognostic factors

Other factors that may be prognostic but with either limited or conflicting data include the following:

- Subsequent neoplasms. Patients with osteosarcoma as a subsequent neoplasm, including tumors arising in a radiation field, share the same prognosis as patients with de novo osteosarcoma if they are treated aggressively with complete surgical resection and multiagent chemotherapy.[rx–rx]

In a German series, approximately 25% of patients with craniofacial osteosarcoma had osteosarcoma as a second tumor, and in 8 of these 13 patients, osteosarcoma arose after treatment for retinoblastoma. In this series, there was no difference in outcome for primary or secondary craniofacial osteosarcoma.[rx]

- Laboratory abnormalities. Possible prognostic factors identified for patients with conventional localized high-grade osteosarcoma include the LDH level, alkaline phosphatase level, and histologic subtype.[rx,rx,rx–rx]

- Body mass index. Higher body mass index at initial presentation is associated with worse OS.[rx]

- Pathologic fracture. Some studies have suggested that a pathologic fracture at diagnosis or during preoperative chemotherapy does not have adverse prognostic significance.[rx]; [rx,rx]; [rx]

However, a systematic review of nine cohort studies examined the impact of pathologic fractures on outcome in patients with osteosarcoma. The review included 2,187 patients, and 311 of these patients had a pathologic fracture. The presence of a pathologic fracture correlated with decreased EFS and OS.[rx] In two additional series, a pathologic fracture at diagnosis was associated with a worse overall outcome.[rx]; [rx] A retrospective analysis of 2,847 patients with osteosarcoma from the German cooperative group identified 321 patients (11.3%) with a pathological fracture before the initiation of systemic therapy.[rx] In pediatric patients, OS and EFS did not differ significantly between patients with and without a pathologic fracture. In adults, the 5-year OS rate in patients with a pathologic fracture was 46% versus 69% for patients without a pathologic fracture (P < .001). The 5-year EFS rate in adults was 36% for patients with a pathologic fracture versus 56% for patients without a pathologic fracture (P < .001). In a multivariable analysis, the presence of a pathologic fracture was not a statistically significant factor for OS or EFS in the total cohort or in pediatric patients. In adult patients, presence of a pathologic fracture remained an independent prognostic factor for OS (hazard ratio, 1.893; P = .013).

- ERBB2 (HER2/NEU) expression. There are conflicting data concerning the prognostic significance of this human epidermal growth factor.[rx–rx]

- Tumor cell ploidy.[65]

- Specific chromosomal gains or losses.[rx]

- Loss of heterozygosity of the RB1 gene.[rx,rx]

- Loss of heterozygosity of the p53 locus.[69]

- Increased expression of p-glycoprotein.[rx,rx] A prospective analysis of p-glycoprotein expression determined by immunohistochemistry failed to identify prognostic significance for patients with newly diagnosed osteosarcoma, although earlier studies suggested that overexpression of p-glycoprotein predicted poor outcome.[rx]

- Time to definitive surgery. In a large series, a delay of 21 days or longer from the time of definitive surgery to the resumption of chemotherapy was an adverse prognostic factor.[rx]

Genomics of Osteosarcoma

Molecular features of osteosarcoma

The genomic landscape of osteosarcoma is distinctive from that of other childhood cancers. It is characterized by an exceptionally high number of structural variants with relatively small numbers of single nucleotide variants compared with many adult cancers.[74,75]

Key observations regarding the genomic landscape of osteosarcoma are summarized below:

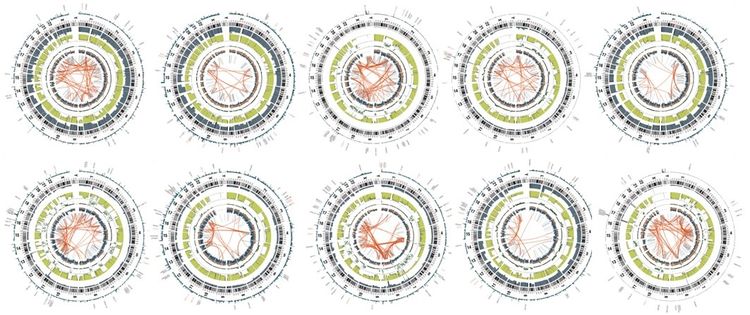

- The number of structural variants observed for osteosarcoma is very high, at more than 200 structural variants per genome;[rx,rx] thus, osteosarcoma has the most chaotic genome among childhood cancers. The Circos plots shown in Figure 1 illustrate the exceptionally high numbers of intra- and inter-chromosomal translocations that typify osteosarcoma genomes.

Figure 1. Circos plots of osteosarcoma cases from the National Cancer Institute’s Therapeutically Applicable Research to Generate Effective Treatments (TARGET) project. The red lines in the interior circle connect chromosome regions involved in either intra- or inter-chromosomal translocations. Osteosarcoma is distinctive from other childhood cancers because it has a large number of intra- and inter-chromosomal translocations. Credit: National Cancer Institute.

- The number of mutations per osteosarcoma genome that affect protein sequence (approximately 25 per genome) is higher than that of some other childhood cancers (e.g., Ewing sarcoma and rhabdoid tumors) but is far below that for adult cancers such as melanoma and non-small cell lung cancer.[rx,rx]

- Genomic alterations in TP53 are present in most osteosarcoma cases, with a distinctive form of TP53 inactivation occurring by structural variations in the first intron of TP53 that lead to disruption of the TP53 gene.[rx] Other mechanisms of TP53 inactivation are also observed, including missense and nonsense mutations and deletions of the TP53 gene.[rx,rx] The combination of these various mechanisms for loss of TP53 function leads to biallelic inactivation in most cases of osteosarcoma.

- MDM2 amplification is observed in a minority of osteosarcoma cases (approximately 5%) and provides another mechanism for loss of TP53 function.[rx,rx]

- RB1 is commonly inactivated in osteosarcoma, sometimes by mutation but more commonly by deletion.[rx,rx]

- Other genes with recurrent alterations in osteosarcoma include ATRX and DLG2.[74] Additionally, pathway analysis showed that the PI3K/mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway was altered by mutation/loss/amplification in approximately one-fourth of patients, with PTEN mutation/loss being the most common alteration.[rx]

- The range of mutations reported for osteosarcoma tumors at diagnosis do not provide obvious therapeutic targets, as they primarily reflect loss of tumor suppressor genes (e.g., TP53, RB1, PTEN) rather than activation of targetable oncogenes.

Several germline mutations are associated with susceptibility to osteosarcoma; Table 1 summarizes the syndromes and associated genes for these conditions. The frequency of pathogenic or likely pathogenic cancer-susceptibility gene variants in individuals with osteosarcoma is 28% greater than that in control groups.[rx]

Mutations in TP53 are the most common germline alterations associated with osteosarcoma. Mutations in this gene are found in approximately 70% of patients with Li-Fraumeni syndrome (LFS), which is associated with increased risk of osteosarcoma, breast cancer, various brain cancers, soft tissue sarcomas, and other cancers. While rhabdomyosarcoma is the most common sarcoma arising in patients aged 5 years and younger with TP53-associated LFS, osteosarcoma is the most common sarcoma in children and adolescents aged 6 to 19 years.[rx] One study observed a high frequency of young osteosarcoma cases (age <30 years) carrying a known LFS-associated or likely LFS-associated TP53 mutation (3.8%) or rare exonic TP53 variant (5.7%), with an overall TP53 mutation frequency of 9.5%.[rxrx] Another study observed germline TP53 mutations in 7 of 59 osteosarcoma cases (12%) subjected to whole-exome sequencing.[rx] Other groups have reported lower rates (3%–7%) of TP53 germline mutations in patients with osteosarcoma.[rx,rx]

| Syndrome | Description | Location | Gene | Function |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AML = acute myeloid leukemia; IL-1 = interleukin-1; MDS = myelodysplastic syndrome; RANKL = receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa beta ligand; TNF = tumor necrosis factor. | ||||

| aAdapted from Kansara et al.[rx] | ||||

| Bloom syndrome [rx] | Rare inherited disorder characterized by short stature and sun-sensitive skin changes. Often presents with a long, narrow face, small lower jaw, large nose, and prominent ears. | 15q26.1 | BLM | DNA helicase |

| Diamond-Blackfan anemia [rx] | Inherited pure red cell aplasia. Patients at risk for MDS and AML. Associated with skeletal abnormalities such as abnormal facial features (flat nasal bridge, widely spaced eyes). | Ribosomal proteins | Ribosome production [rx,rx] | |

| Li-Fraumeni syndrome [rx] | Inherited mutation in TP53 gene. Affected family members at increased risk of bone tumors, breast cancer, leukemia, brain tumors, and sarcomas. | 17p13.1 | P53 | DNA damage response |

| Paget disease [rx] | Excessive breakdown of bone with abnormal bone formation and remodeling, resulting in pain from weak, malformed bone. | 18q21-qa22 | LOH18CR1 | IL-1/TNF signaling; RANKL signaling pathway |

| 5q31 | ||||

| 5q35-qter | ||||

| Retinoblastoma [rx] | Malignant tumor of the retina. Approximately 66% of patients are diagnosed by age 2 years and 95% of patients by age 3 years. Patients with heritable germ cell mutations at greater risk of subsequent neoplasms. | 13q14.2 | RB1 | Cell-cycle checkpoint |

| Rothmund-Thomson syndrome (also called poikiloderma congenitale) [rx,rx] | Autosomal recessive condition. Associated with skin findings (atrophy, telangiectasias, pigmentation), sparse hair, cataracts, small stature, and skeletal abnormalities. Increased incidence of osteosarcoma at a younger age. | 8q24.3 | RECQL4 | DNA helicase |

| Werner syndrome [rx] | Patients often have short stature and in their early twenties, develop signs of aging, including graying of hair and hardening of skin. Other aging problems such as cataracts, skin ulcers, and atherosclerosis develop later. | 8p12-p11.2 | WRN | DNA helicase; exonuclease activity |

Refer to the following PDQ summaries for more information about these genetic syndromes:

Evaluation of Response to Initial Therapy

Imaging modalities such as dynamic magnetic resonance imaging or positron emission tomography scanning are under investigation as noninvasive methods to assess response.[rx–rx]

Central (Medullary) Tumors

- Conventional central osteosarcomas. The most common pathologic subtype is conventional central osteosarcoma, which is characterized by areas of necrosis, atypical mitoses, and malignant osteoid tissue and/or cartilage. The other subtypes are much less common, each occurring at a frequency of less than 5%.

- Telangiectatic osteosarcomas.[rx,rx] Telangiectatic osteosarcoma may be confused radiographically with an aneurysmal bone cyst or giant cell tumor. This variant should be approached as a conventional osteosarcoma.[rx,rx]

- Intraosseous well-differentiated (low-grade) osteosarcomas.

- Small-cell osteosarcomas.

Surface (Peripheral) Tumors

Parosteal and Periosteal Osteosarcoma

Parosteal osteosarcoma is defined as a lesion arising from the surface of the bone with a well-differentiated appearance on imaging and low-grade histological features.[rx] The most common site for parosteal osteosarcoma is the posterior distal femur. Parosteal osteosarcoma occurs more often in older patients than does conventional high-grade osteosarcoma and is most common in patients aged 20 to 30 years. Parosteal osteosarcoma can be treated successfully with wide excision of the primary tumor alone.[rx,rx]

Periosteal osteosarcoma typically appears as a broad-based soft tissue mass with extrinsic erosion of the underlying bony cortex.[rx] Pathology shows an intermediate grade of differentiation. In a series of 119 patients, metastasis was reported in 17 patients.[rx] Wide resection is essential. A single-institution retrospective review identified 29 patients with periosteal osteosarcoma.[rx] The 5-year disease-free survival rate was 83%. The authors could not make a definitive statement regarding the benefits of adjuvant chemotherapy. Another single-institution retrospective review identified 33 patients with periosteal osteosarcoma.[rx] The 10-year overall survival (OS) rate was 84%. The 10-year OS rate was 83% for patients who were treated with surgery alone and 86% for patients who were treated with surgery and chemotherapy. The European Musculoskeletal Oncology Society retrospectively analyzed 119 patients with periosteal osteosarcoma.[9] The OS rate was 89% at 5 years and 83% at 10 years. Eighty-one patients received chemotherapy; 50 of those patients received chemotherapy before definitive surgical resection. There was no difference in outcome between the patients who received chemotherapy and the patients who did not receive chemotherapy.

The terms parosteal and periosteal osteosarcoma are embedded in the literature and widely used. They are confusing to patients and practitioners. It would be more helpful to divide osteosarcoma by location and histological grade. High-grade osteosarcoma, sometimes referred to as conventional osteosarcoma, typically arises centrally and grows outward, destroying surrounding cortex and soft tissues, but there are unequivocal cases of high-grade osteosarcoma in surface locations.[rx] Similarly, there are reports of low-grade osteosarcoma arising in the medullary cavity.

Extraosseous Osteosarcoma

Extraosseous osteosarcoma is a malignant mesenchymal neoplasm without direct attachment to the skeletal system. Previously, treatment for extraosseous osteosarcoma followed soft tissue sarcoma guidelines,[rx] although a retrospective analysis of the cooperative German-Austrian-Swiss osteosarcoma study group identified a favorable outcome for extraosseous osteosarcoma treated with surgery and conventional osteosarcoma therapy.[rx]

Undifferentiated Pleomorphic Sarcoma (UPS) of Bone

UPS of bone should be distinguished from angiomatoid fibrous histiocytoma, a low-grade tumor that is usually noninvasive, small, and associated with an excellent outcome using surgery alone.[rx] One study suggests similar event-free survival rates for UPS and osteosarcoma.[rx]

Staging and Site Information for Osteosarcoma and UPS of Bone

Historically, the Enneking staging system for skeletal malignancies was used.[1] This system inferred the aggressiveness of the primary tumor by the descriptors intracompartmental or extracompartmental. The American Joint Committee on Cancer’s tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) staging system for malignant bone tumors is not widely used for pediatric osteosarcoma, and patients are not stratified on the basis of prognostic stage groups.

For the purposes of treatment, osteosarcoma is described as one of the following:

- Localized. Patients without clinically detectable metastatic disease are considered to have localized osteosarcoma.

- Metastatic. Patients with any site of metastasis at the time of initial presentation detected by routine clinical studies are considered to have metastatic osteosarcoma.

Localized Osteosarcoma

Localized tumors are limited to the bone of origin. Patients with skip lesions confined to the bone that includes the primary tumor are considered to have localized disease if the skip lesions can be included in the planned surgical resection.[2] Approximately one-half of the tumors arise in the femur; of these, 80% are in the distal femur. Other primary sites, in descending order of frequency, are the proximal tibia, proximal humerus, pelvis, jaw, fibula, and ribs.[3] Osteosarcoma of the head and neck is more likely to be low grade [4] and to arise in older patients than is osteosarcoma of the appendicular skeleton.

Metastatic Osteosarcoma

Radiologic evidence of metastatic tumor deposits in the lungs, other bones, or other distant sites is found in approximately 20% of patients at diagnosis, with 85% to 90% of metastatic disease presenting in the lungs. The second most common site of metastasis is another bone.[rx] Metastasis to other bones may be solitary or multiple. The syndrome of multifocal osteosarcoma refers to a presentation with multiple foci of osteosarcoma without a clear primary tumor, often with symmetrical metaphyseal involvement.[rx]

Staging Evaluation

For patients with confirmed osteosarcoma, in addition to plain radiographs of the primary site that include a single-plane view of the entire affected bone to assess for skip metastasis, pretreatment staging studies should include the following:[rx]

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the primary site to include the entire bone.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan, if MRI is not available.

- Bone scan.

- Posteroanterior and lateral chest radiograph.

- CT scan of the chest.

Positron emission tomography (PET) using fluorine F 18-fludeoxyglucose is an optional staging modality.

A retrospective review of 206 patients with osteosarcoma compared bone scan, PET scan, and PET-CT scan for the detection of bone metastases.[rx] PET-CT was more sensitive and accurate than bone scan, and the combined use of both imaging studies achieved the highest sensitivity for diagnosing bone metastases in osteosarcoma.

Treatment Option Overview for Osteosarcoma and UPS of Bone

Successful treatment generally requires the combination of effective systemic chemotherapy and complete resection of all clinically detectable disease. Protective weight bearing is recommended for patients with tumors of weight-bearing bones to prevent pathological fractures that could preclude limb-preserving surgery.

It is imperative that patients with proven or suspected osteosarcoma have an initial evaluation by an orthopedic oncologist familiar with the surgical management of this disease. This evaluation, which includes imaging studies, should be done before the initial biopsy, because an inappropriately performed biopsy may jeopardize a limb-sparing procedure.

Randomized clinical trials have established that both neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy are effective in preventing relapse in patients with clinically nonmetastatic tumors.[rx]; [rx][Level of evidence: 1iiA] The Pediatric Oncology Group conducted a study in which patients were randomly assigned to either immediate amputation or amputation after neoadjuvant therapy. A large percentage of patients declined to be assigned randomly, and the study was terminated without approaching the stated accrual goals. In the small number of patients treated, there was no difference in outcome for those who received preoperative versus postoperative chemotherapy.[rx]

The treatment of osteosarcoma also depends on the histologic grade, as follows:

- High-grade osteosarcoma. High-grade osteosarcoma requires surgery and systemic chemotherapy whether it arises in the conventional central location or on a bone surface.

- Low-grade osteosarcoma. Low-grade osteosarcoma can be treated successfully by wide surgical resection alone, regardless of site of origin.

- Intermediate-grade osteosarcoma. Pathologists sometimes characterize tumors as intermediate-grade osteosarcoma. It is difficult to make treatment decisions for intermediate-grade tumors. When a tumor biopsy suggests an intermediate-grade osteosarcoma, an option is to proceed with wide resection. The availability of the entire tumor allows the pathologist to examine more tissue and evaluate soft tissue and lymphovascular invasion, which can often clarify the nature of the lesion.

- If the lesion proves to have high-grade elements, systemic chemotherapy is indicated, just as it would be for any high-grade osteosarcoma. The Pediatric Oncology Group performed a study in which high-grade osteosarcoma patients were randomly assigned to either immediate definitive surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy or to an initial period of chemotherapy followed by definitive surgery.[rx] The outcome was the same for both groups. Although the strategy of initial chemotherapy followed by definitive surgery has become an almost universally applied approach for osteosarcoma, this study suggests that there is no increased risk of treatment failure if definitive surgery is done before chemotherapy begins; this can help to clarify equivocal diagnoses of intermediate-grade osteosarcoma.

Recognition of intraosseous well-differentiated osteosarcoma and parosteal osteosarcoma is important because these tumor types are associated with the most favorable prognosis and can be treated successfully with wide excision of the primary tumor alone.[rx,rx] Periosteal osteosarcoma has a generally good prognosis [rx] and treatment is guided by histologic grade.[rx,rx]

| Treatment Group | Treatment Options | |

|---|---|---|

| Localized osteosarcoma and UPS of bone | Surgical removal of primary tumor. | |

| Chemotherapy. | ||

| Radiation therapy, if surgery is not feasible or surgical margins are inadequate. | ||

| Osteosarcoma and UPS of bone with metastatic disease at diagnosis: | Chemotherapy. | |

| Lung-only metastases | Preoperative chemotherapy followed by surgery to remove the tumor followed by postoperative combination chemotherapy. | |

| Bone-only metastases or bone with lung metastases | Preoperative chemotherapy followed by surgery to remove the primary tumor and all metastatic disease followed by postoperative combination chemotherapy. | |

| Surgery to remove the primary tumor followed by chemotherapy and then surgical resection of metastatic disease followed by postoperative combination chemotherapy. | ||

| Recurrent osteosarcoma and UPS of bone: | Surgery to remove all sites of metastatic disease. | |

| Chemotherapy. | ||

| Targeted therapy. | ||

| Radiation therapy. | ||

| Lung-only recurrence | Surgery to remove the tumor. | |

| Recurrence with bone-only metastases | Surgery to remove the tumor. | |

| 153Sm-EDTMP with or without stem cell support. | ||

| Second recurrence of osteosarcoma | Surgery to remove the tumor. | |

| 153Sm-EDTMP = samarium Sm 153-ethylenediamine tetramethylene phosphonic acid. | ||

Special Considerations for the Treatment of Children With Cancer

Cancer in children and adolescents is rare, although the overall incidence of childhood cancer has been slowly increasing since 1975.[rx] Children and adolescents with cancer should be referred to medical centers that have a multidisciplinary team of cancer specialists with experience treating the cancers that occur during childhood and adolescence. This multidisciplinary team approach incorporates the skills of the following health care professionals and others to ensure that children receive treatment, supportive care, and rehabilitation that will achieve optimal survival and quality of life:

- Primary care physicians.

- Orthopedic surgeon experienced in bone tumors.

- Pathologists.

- Radiation oncologists.

- Pediatric oncologists.

- Rehabilitation specialists.

- Pediatric nurse specialists.

- Social workers.

- Child-life professionals.

- Psychologists.

(Refer to the PDQ summaries on Supportive and Palliative Care for specific information about supportive care for children and adolescents with cancer.)

Guidelines for pediatric cancer centers and their role in the treatment of pediatric patients with cancer have been outlined by the American Academy of Pediatrics.[rx] At these pediatric cancer centers, clinical trials are available for most types of cancer that occur in children and adolescents, and the opportunity to participate in these trials is offered to most patients and their families. Clinical trials for children and adolescents with cancer are generally designed to compare potentially better therapy with therapy that is currently accepted as standard. Most of the progress made in identifying curative therapies for childhood cancers has been achieved through clinical trials. Information about ongoing clinical trials is available from the National Cancer Institute’s website.

Childhood and adolescent cancer survivors require close monitoring because cancer therapy side effects may persist or develop months or years after treatment. (Refer to the PDQ summary on Late Effects of Treatment for Childhood Cancer for specific information about the incidence, type, and monitoring of late effects in childhood and adolescent cancer survivors.)

Treatment of Localized Osteosarcoma and UPS of Bone

Patients with localized osteosarcoma undergoing surgery and chemotherapy have a 5-year overall survival (OS) rate of 62% to 65%.[rx] Complete surgical resection is crucial for patients with localized osteosarcoma; however, at least 80% of patients treated with surgery alone will develop metastatic disease.[rx] Randomized clinical trials have established that adjuvant chemotherapy is effective in preventing relapse or recurrence in patients with localized resectable primary tumors.[rx]; [rx]

Undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) of bone is seen more commonly in older adults. Patients with UPS of bone are treated according to osteosarcoma treatment protocols, and the outcome for patients with resectable UPS is similar to the outcome for patients with osteosarcoma.[rx] As with osteosarcoma, patients with favorable necrosis (≥90% necrosis) have a longer survival than do those with an inferior necrosis (<90% necrosis).[rx] Many patients with UPS will need preoperative chemotherapy to achieve a wide local excision.[6]

Treatment options for patients with localized osteosarcoma or UPS of bone include the following: Surgical resection of the primary tumor with adequate margins is an essential component of the curative strategy for patients with localized osteosarcoma. The type of surgery required for complete ablation of the primary tumor depends on a number of factors that must be evaluated on a case-by-case basis.[rx]

In general, more than 80% of patients with extremity osteosarcoma can be treated by a limb-sparing procedure and do not require amputation.[rx] Limb-sparing procedures are planned only when the preoperative staging indicates that it would be possible to achieve wide surgical margins. In one study, patients undergoing limb-salvage procedures who had poor histologic response and close surgical margins had a high rate of local recurrence.[rx]

Reconstruction after limb-sparing surgery can be accomplished with many options, including metallic endoprosthesis, allograft, vascularized autologous bone graft, and rotationplasty. An additional option, osteogenesis distraction bone transport, is available for patients whose tumors do not involve the epiphysis of long bones.[rx] This procedure results in a stable reconstruction that functionally restores the normal limb. The choice of optimal surgical reconstruction involves many factors, including the following:[rx]

If a complicated reconstruction delays or prohibits the resumption of systemic chemotherapy, limb preservation may endanger the chance for cure. In retrospective analyses of 703 patients with localized osteosarcoma, the resumption of chemotherapy 21 days or more after definitive surgery was associated with an increased risk of death and adverse events (hazard ratio [HR], 1.57; 1.04–2.36).[rx] Delays in total time to completion of chemotherapy have also been associated with inferior overall survival (OS) and event-free survival (EFS). In a retrospective multivariate analysis of 113 patients with localized osteosarcoma, a delay of time to completion of chemotherapy greater than 4 weeks was associated with an OS HR of 2.70 (1.11–6.76, P = .003) and an EFS HR of 1.13 (1.00–1.26, P = .016).[12]

For some patients, amputation remains the optimal choice for management of the primary tumor. A pathologic fracture noted at diagnosis or during preoperative chemotherapy does not preclude limb-salvage surgery if wide surgical margins can be achieved.[13] If the pathologic examination of the surgical specimen shows inadequate margins, an immediate amputation should be considered, especially if the histologic necrosis after preoperative chemotherapy was poor.[rx]

The German Cooperative Osteosarcoma Study performed a retrospective analysis of 1,802 patients with localized and metastatic osteosarcoma who underwent surgical resection of all clinically detectable disease.[rx][Level of evidence: 3iiA] Local recurrence (n = 76) was associated with a high risk of death from osteosarcoma. Factors associated with an increased risk of local recurrence included nonparticipation in a clinical trial, pelvic primary site, limb-preserving surgery, soft tissue infiltration beyond the periosteum, poor pathologic response to initial chemotherapy, failure to complete planned chemotherapy, and performing the biopsy at an institution different from where the definitive surgery is being performed. Patients who undergo amputation have lower local recurrence rates than do patients who undergo limb-salvage procedures.[rx] There is no difference in OS between patients initially treated with amputation and those treated with a limb-sparing procedure. Patients with tumors of the femur have a higher local recurrence rate than do patients with primary tumors of the tibia or fibula. Rotationplasty and other limb-salvage procedures have been evaluated for both their functional outcome and their effect on survival. While limb-sparing resection is the current practice for local control at most pediatric institutions, there are few data to indicate that salvage of the lower limb is substantially superior to amputation with regard to patient quality of life.[rx]

Almost all patients receive intravenous preoperative chemotherapy as initial treatment. However, a standard chemotherapy regimen has not been determined. Current chemotherapy protocols include combinations of the following agents: high-dose methotrexate, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, cisplatin, ifosfamide, etoposide, and carboplatin.[rx–rx]

Evidence (preoperative chemotherapy): Historically, the extent of tumor necrosis was used in some clinical trials to determine postoperative chemotherapy. In general, if tumor necrosis exceeded 90%, the preoperative chemotherapy regimen was continued. If tumor necrosis was less than 90%, some groups incorporated drugs not previously utilized in the preoperative therapy. Patients with less necrosis after initial chemotherapy have a prognosis that is inferior to the prognosis for patients with more necrosis. The prognosis is still substantially better than the prognosis for patients treated with surgery alone and no adjuvant chemotherapy. Based on the following evidence, it is inappropriate to conclude that patients with less necrosis have not responded to chemotherapy and that adjuvant chemotherapy should be withheld for these patients. Chemotherapy after definitive surgery should include the agents used in the initial phase of treatment unless there is clear and unequivocal progressive disease during the initial phase of therapy. Evidence (postoperative chemotherapy): The Italian Sarcoma Group and the Scandinavian Sarcoma Group performed a clinical trial in patients with osteosarcoma who presented with clinically detectable metastatic disease.[rx] Consolidation with high-dose etoposide and carboplatin followed by autologous stem cell reconstitution did not appear to improve outcome and the investigators do not recommend this strategy for the treatment of osteosarcoma. Laboratory studies using cell lines and xenografts suggested that bisphosphonates had activity against osteosarcoma.[rx] A single-institution clinical trial demonstrated that pamidronate could safely be administered contemporaneously with multiagent chemotherapy to patients with newly diagnosed osteosarcoma.[rx] The French pediatric and adult sarcoma cooperative groups performed a prospective trial for the treatment of osteosarcoma.[rx] All patients received multiagent chemotherapy, and patients were randomly assigned to receive or not to receive zoledronate. The addition of zoledronate did not improve EFS. If complete surgical resection is not feasible or if surgical margins are inadequate, radiation therapy may improve the local control rate.[rx,rx]; [rx][Level of evidence: 3iiA] Radiation therapy should be considered in patients with osteosarcoma of the head and neck who have positive or uncertain resection margins.[rx][Level of evidence: 3iiA]

Evidence (radiation therapy for local control): Osteosarcoma of the head and neck occurs in an older population than does osteosarcoma of the extremities.[rx,rx–rx] In the pediatric age group, osteosarcomas of the head and neck are more likely to be low-grade or intermediate-grade tumors than are osteosarcomas of the extremities.[rx,rx] All reported series emphasize the need for complete surgical resection.[rx,rx–rx][Level of evidence: 3iiiA] The probability for cure with surgery alone is higher for osteosarcoma of the head and neck than it is for extremity osteosarcoma. When surgical margins are positive, there is a trend for improved survival with adjuvant radiation therapy.[,rxrx][Level of evidence: 3iiiA]

There are no randomized trials to assess the efficacy of chemotherapy in patients with osteosarcoma of the head and neck, but several series suggest a benefit.[rx,rx] Chemotherapy should be considered for younger patients with high-grade osteosarcoma of the head and neck.[rx,rx]

Patients with osteosarcoma of the head and neck have a higher risk of developing a local recurrence and a lower risk of having distant metastasis than do patients with osteosarcoma of the extremities.[rx,rx,rx,rx]

Use our advanced clinical tal search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria.Treatment Options for Localized Osteosarcoma and UPS of Bone

Surgical removal of primary tumor

Chemotherapy

Preoperative chemotherapy

Postoperative chemotherapy

Other chemotherapy approaches not considered effective

Radiation therapy

Osteosarcoma of the Head and Neck

Current Clinical Trials

Treatment of Osteosarcoma and UPS of Bone With Metastatic Disease at Diagnosis

Approximately 20% to 25% of patients with osteosarcoma present with clinically detectable metastatic disease. For patients with metastatic disease at initial presentation, roughly 20% will remain continuously free of disease, and roughly 30% will survive 5 years from diagnosis.

The lung is the most common site of initial metastatic disease.[rx] Patients with metastases limited to the lungs have a better outcome than do patients with metastases to other sites or to the lungs combined with other sites.[rx,rx]

Treatment options for patients with osteosarcoma or undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) of bone with metastatic disease at diagnosis include the following: The chemotherapeutic agents used include high-dose methotrexate, doxorubicin, cisplatin, high-dose ifosfamide, etoposide, and, in some reports, carboplatin or cyclophosphamide. Evidence (chemotherapy): In the international European and American Osteosarcoma Study (EURAMOS) group consortium, 362 of 2,186 patients (17%) presented with metastasis at diagnosis.[rx][Level of evidence: 1iiA]

The treatment options for UPS of bone with metastasis at initial presentation are the same as the treatment for osteosarcoma with metastasis. Patients with unresectable or metastatic UPS have a very poor outcome.[7]

Treatment options for patients with metastatic lung lesions at diagnosis include the following: Patients with metastatic lung lesions as the sole site of metastatic disease should have the lung lesions resected if possible. Generally, this is performed after the administration of preoperative chemotherapy. After definitive surgical resection of the primary tumor, most clinicians resume systemic chemotherapy before initiating lung surgery to avoid longer delays in the resumption of chemotherapy. In approximately 10% of patients, all lung lesions disappear after preoperative chemotherapy.[3] Complete resection of pulmonary metastatic disease can be achieved in a high percentage of patients with residual lung nodules after preoperative chemotherapy. The cure rate is essentially zero without complete resection of residual pulmonary metastatic lesions. For patients who present with primary osteosarcoma and metastases limited to the lungs and who achieve complete surgical remission, the 5-year EFS rate is approximately 20% to 25%. Multiple metastatic nodules confer a worse prognosis than do one or two nodules, and bilateral lung involvement is worse than unilateral.[rx] Patients with peripheral lung lesions may have a better prognosis than patients with central lesions.[rx] Patients with fewer than three nodules confined to one lung may achieve a 5-year EFS rate of approximately 40% to 50%.[1]

The second most common site of metastasis is another bone that is distant from the primary tumor. Patients with metastasis to other bones distant from the primary tumor experience EFS and OS rates of approximately 10%.[1] In the Italian experience, of the patients who presented with primary extremity tumors and synchronous metastasis to other bones, only 3 of 46 patients remained continuously disease-free 5 years later.[rx] Patients who have transarticular skip lesions have a poor prognosis.[rx]

Multifocal osteosarcoma is different from osteosarcoma that presents with a clearly delineated primary lesion and limited bone metastasis. Multifocal osteosarcoma classically presents with symmetrical, metaphyseal lesions, and it may be difficult to determine the primary lesion. Patients with multifocal bone disease at presentation have an extremely poor prognosis. No patient with synchronous multifocal osteosarcoma has ever been reported to be cured, but treatment with systemic chemotherapy and aggressive surgical resection may significantly prolong life.[rx,rx]

Treatment options for patients with bone-only or bone with lung metastases include the following: When the usual treatment course of preoperative chemotherapy followed by surgical ablation of the primary tumor and resection of all overt metastatic disease followed by postoperative combination chemotherapy cannot be used, an alternative treatment approach may be used. This alternative treatment approach begins with surgery for the primary tumor, followed by chemotherapy, and then surgical resection of metastatic disease. This alternative approach may be appropriate in patients with intractable pain, pathologic fracture, or uncontrolled infection of the tumor when initiation of chemotherapy could create risk of sepsis. Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.Treatment Options for Osteosarcoma and UPS of Bone With Metastatic Disease at Diagnosis

Treatment Options for Lung-Only Metastases at Diagnosis

Treatment Options for Bone-Only Metastases or Bone With Lung Metastases

Current Clinical Trials

Treatment of Recurrent Osteosarcoma and UPS of Bone

Approximately 50% of relapses in patients with recurrent osteosarcoma occur within 18 months of therapy termination, and only 5% of recurrences develop beyond 5 years.[rx–rx]

Prognostic factors for recurrent osteosarcoma or undifferentiated pleomorphic sarcoma (UPS) of bone include the following:

- Time from diagnosis. In 564 patients with a recurrence, patients whose disease recurred within 2 years of diagnosis had a worse prognosis than did patients whose disease recurred after 2 years.[rx] In another series of 431 patients, recurrences occurring less than 2 years from diagnosis were also associated with worse outcomes.[rx]

- Age at initial diagnosis. Older age at initial study enrollment was associated with a worse prognosis.[rx]

- Presence of metastatic disease at diagnosis. The presence of metastatic disease at initial presentation was associated with a worse prognosis.[rx]

- Tumor response to preoperative chemotherapy – Patients with a good histologic response to initial preoperative chemotherapy had a better overall survival (OS) after recurrence than did poor initial responders.[rx]

- Site of metastases – The probability of developing lung metastases at 5 years is 28% in patients presenting with localized disease.[rx] In two large series, the incidence of recurrence by site was as follows: lung only (65%–80%), bone only (8%–10%), local recurrence only (4%–7%), and combined relapse (10%–15%).[rx,rx] Abdominal metastases are rare but may occur as late as 4 years after diagnosis.[rz] The Children’s Oncology Group (COG) reported the outcomes of 431 young patients with recurrent osteosarcoma.[rx]Patients with recurrences in both lung and bone had worse outcomes than did patients with recurrences in lung only (P = .005).

- Surgical resectability – Patients with recurrent osteosarcoma should be assessed for surgical resectability, because they may sometimes be cured with aggressive surgical resection with or without chemotherapy.[rx,rx,rx–rx] Control of osteosarcoma after recurrence depends on complete surgical resection of all sites of clinically detectable metastatic disease. If surgical resection is not attempted or cannot be performed, progression and death are certain. The ability to achieve a complete resection of recurrent disease is the most important prognostic factor at first relapse, with a 5-year survival rate of 20% to 45% after complete resection of metastatic pulmonary tumors and a 20% survival rate after complete resection of metastases at other sites.[rx,rx,rx,rx]

Treatment Options for Recurrent Osteosarcoma and UPS of Bone

Treatment options for patients with recurrent osteosarcoma or UPS of bone include the following:

- Surgery to remove all sites of metastatic disease.

- Chemotherapy.

- Targeted therapy.

- Radiation therapy.

The role of systemic chemotherapy for the treatment of patients with recurrent osteosarcoma is not well defined. The selection of further systemic treatment depends on many factors, including the site of recurrence, the patient’s previous primary treatment, and individual patient considerations.

The COG reported the outcomes of patients with recurrent osteosarcoma from seven phase II trials, all of which were assessed to have shown no treatment benefit.[15] The event-free survival (EFS) rate for 96 patients with osteosarcoma and measurable disease was 12% at 4 months (95% confidence interval [CI], 6%–19%). There was no significant difference in EFS between the trials according to number of previous treatment regimens or patient age, sex, and ethnicity. One additional phase II trial with a different study design was reported. In this trial, patients with osteosarcoma and metastases to the lung underwent surgical resection of all lung nodules and then were treated with adjuvant inhaled granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF). The 12-month EFS rate for the 42 evaluable patients enrolled in this study was 20% (95% CI, 10%–34%).

The following chemotherapy and targeted therapy agents have been studied to treat recurrent osteosarcoma and UPS of bone:

- Ifosfamide alone with mesna uroprotection, or in combination with etoposide – Ifosfamide alone with mesna uroprotection, or in combination with etoposide, has been active in as many as one-third of patients with recurrent osteosarcoma who have not previously received this drug.[rx–rx]

- Gemcitabine and docetaxel – A nonrandomized comparison of two doses of gemcitabine, both given with docetaxel, suggested that a higher dose of gemcitabine (900 mg/m2) was associated with a better response rate and longer survival than was a lower dose of gemcitabine (675 mg/m2) for recurrent or refractory osteosarcoma.[rx][Level of evidence: 3iiA] The combination of gemcitabine (at a dose of 900 mg/m2) and docetaxel has also been reported to have activity in some studies that included patients with unresectable disease.[rx–rx]; [rx][Level of evidence: 3iiDiv]

- Cyclophosphamide and etoposide – Cyclophosphamide and etoposide have been shown to have activity in recurrent osteosarcoma.[rx]

- Sorafenib – The Italian Sarcoma Group reported rare objective responses and disease stabilization with sorafenib in patients with recurrent osteosarcoma.[rx]

- Sorafenib and everolimus – The Italian Sarcoma Group also reported the outcome of patients with metastatic recurrent osteosarcoma treated with the combination of sorafenib and everolimus. They observed two partial responses and two minor responses in 38 patients; 17 of 38 patients were progression free at 6 months from study entry but toxicity was greater than with sorafenib monotherapy.[rx][Level of evidence: 2Diii]

- Regorafenib – Two prospective, randomized, double-blind trials have evaluated the role of regorafenib in the treatment of metastatic recurrent osteosarcoma. Both studies used the approved treatment regimen of 160 mg by mouth daily for 21 days followed by 7 days without treatment. The French trial randomly assigned patients 2:1 between regorafenib and placebo and allowed crossover for patients assigned to placebo.[rx] Seventeen of 26 patients (65%; one-sided 95% CI, 47%) in the regorafenib group did not have disease progression at 8 weeks, compared with 0 of 12 patients in the placebo group. The Sarcoma Alliance for Research Collaboration (SARC) group randomly assigned adult patients 1:1 between regorafenib and placebo.[rx] Median progression-free survival was significantly improved with regorafenib versus placebo: 3.6 months (95% CI, 2.0–7.6 months) versus 1.7 months (95% CI, 1.2–1.8 months), respectively (hazard ratio, 0.42; 95% CI, 0.21–0.85; P = .017).

High-dose samarium Sm 153-ethylenediamine tetramethylene phosphonic acid (153Sm-EDTMP) coupled with peripheral blood stem cell support may provide significant pain palliation in patients with bone metastases.[rx–rx] Toxicity of 153Sm-EDTMP is primarily hematologic.[rx][Level of evidence: 3iiDiii]

A single-institution retrospective review reported that high-dose fraction radiation therapy (2 Gy/fraction) was a useful form of palliation for patients with recurrent osteosarcoma.[rx][Level of evidence: 3iiiDiv] Thirty-two courses of palliative radiation therapy were given to 20 patients with symptomatic metastatic and/or locally recurrent primary disease. Twenty-four of the 32 courses (75%) were associated with symptom improvement. Higher doses of radiation therapy correlated with longer durations of symptom response.

Treatment Options for Lung-Only Recurrence

Repeated resections of pulmonary recurrences can lead to extended disease control and possibly cure for some patients.[rx,rx] Survival for patients with unresectable metastatic disease is less than 5%.[rx,rx] The 5-year EFS rate for patients who have complete surgical resection of all pulmonary metastases ranges from 20% to 45%.[rx,rx,rx]; [rx][Level of evidence: 3iiiA]

Factors associated with a better outcome include fewer pulmonary nodules, unilateral pulmonary metastases, longer intervals between primary tumor resection and metastases, and tumor location in the periphery of the lung.[rx,rx,rx,rx,x] Approximately 50% of patients with one isolated pulmonary lesion more than 1 year after diagnosis were long-term survivors after metastasectomy. Chemotherapy did not appear to offer an advantage.[rx][Level of evidence: 3iiiA]

Treatment options for patients with osteosarcoma and UPS of bone that has recurred in the lung only include the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor.

Control of osteosarcoma requires surgical resection of all macroscopic tumors. Several options are available to resect pulmonary nodules in a patient with osteosarcoma, including thoracoscopy and thoracotomy with palpation of the collapsed lung. When patients have nodules identified only in one lung, some surgeons advocate thoracoscopy; some advocate unilateral thoracotomy; and some advocate bilateral thoracotomy. Bilateral thoracotomy can be performed as a single surgical procedure with a median sternotomy or a clamshell approach, or by staged bilateral thoracotomies.

Recommendations are conflicting regarding the surgical approach to the treatment of pulmonary metastases in osteosarcoma.

Evidence (surgical approach for lung-only recurrence of osteosarcoma and UPS of bone):

- The St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital reported on 81 patients who had pulmonary nodules identified at initial presentation in only one lung by computed tomography (CT) scan.[rx] They performed unilateral thoracotomy and did not explore the contralateral hemithorax. At the time of thoracotomy, 44 of 81 patients had a solitary nodule identified; 15 of 81 patients had two nodules identified; 16 of 81 patients had three to five nodules identified; and 6 of 81 patients had more than five nodules identified. Additional patients who were considered unresectable were not included in the analysis.

- Thirty-nine of 81 patients had subsequent pulmonary recurrence; for most patients, recurrence occurred within 6 months.

- Within the first 6 months, 9 of 81 patients had ipsilateral recurrence, and 10 of 81 patients had a contralateral recurrence. By 2 years after initial thoracotomy, 13 of 81 patients had ipsilateral recurrence; 19 of 81 patients had contralateral recurrence; and 2 of 81 patients had bilateral recurrence.

- OS was similar for patients with ipsilateral and bilateral recurrence.

- The Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center reported on pulmonary metastatic disease recurrence after initial therapy for osteosarcoma. Fourteen patients had pulmonary nodules identified in only one lung by CT scan; nine patients were identified less than 2 years from initial diagnosis (early metastases), and five patients were identified more than 2 years from initial diagnosis (late metastases).[rx] Seven of nine patients with early metastases had staged contralateral thoracotomies, and six of seven had nodules removed from the contralateral lung, despite negative CT scan findings.

- The lack of a comparison group precludes evaluation of the impact of the contralateral thoracotomy on subsequent EFS or OS.

- The same group expanded their analysis to include a retrospective review of 161 thoracotomies performed in 88 patients with osteosarcoma metastatic to the lung.[rx] In this expanded series, CT failed to identify one-third of pulmonary metastases confirmed by pathologic examination.

Treatment Options for Recurrence With Bone-Only Metastases

Treatment options for patients with osteosarcoma or UPS of bone that has recurred in the bone only include the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor.

- 153Sm-EDTMP with or without stem cell support.

Patients with osteosarcoma who develop bone metastases have a poor prognosis. In one large series, the 5-year EFS rate was 11%.[rx] Patients with late solitary bone relapse have a 5-year EFS rate of approximately 30%.[rx–rx]

For patients with multiple unresectable bone lesions, 153Sm-EDTMP with or without stem cell support may produce stable disease and/or provide pain relief.[rx]

Treatment Options for Local Recurrence

The postrelapse outcome of patients who have a local recurrence is quite poor.[rx–rx] Two retrospective, single-institution series reported a survival rate of 10% to 40% after local recurrence without associated systemic metastasis.[rx–rx] A retrospective review from the Italian Sarcoma Group identified 62 patients (median age, 21 years) with local recurrences.[rx] With a median follow-up of 43 months (range, 5–235 months), the 5-year post–local relapse survival rate was 37%, significantly better for patients with a longer local recurrence–free interval (≤24 months, 31% vs. >24 months, 61.5%; P = .03), absence of distant metastases (no distant metastases, 56% vs. distant metastases, 11.5%; P = .0001), and achievement of second complete remission (CR2) by surgical resection (no CR2, 0% vs. CR2, 58.5%; P = .0001). No difference in post–local relapse survival was found according to age, and there was no benefit from chemotherapy administration.

Survival of patients with local recurrences and either previous or concurrent systemic metastases is poor.[rx]

The incidence of local relapse was higher in patients who had a poor pathologic response to chemotherapy in the primary tumor and in patients with inadequate surgical margins.[rx,rx]

Treatment Options for Second Recurrence of Osteosarcoma

Treatment options for patients with osteosarcoma or UPS of bone that has recurred twice include the following:

- Surgery to remove the tumor.

The cooperative German-Austrian-Swiss osteosarcoma study group reported on 249 patients who had a second recurrence of osteosarcoma. The main feature of therapy was repeated surgical resection of recurrent disease. Of these patients, 197 died and 37 were alive in CR (24 patients after a third complete response and 13 patients after a fourth or subsequent complete response). Fifteen patients who did not achieve surgical remission remained alive, but follow-up for these patients was extremely short.[rx]

The Spanish Group for Research on Sarcoma reported the results of a phase II trial of patients with relapsed or refractory osteosarcoma who were treated with gemcitabine and sirolimus.[rx][Level of evidence: 3iiDiv] The progression-free survival (PFS) rate at 4 months was 44%; after central radiologic review of 33 assessable patients, 2 partial responses and 14 disease stabilizations (48.5%) were reported.

The COG reported the outcomes of patients with recurrent osteosarcoma from seven phase II trials, all of which were assessed to have shown no treatment benefit.[rx] The EFS rate for 96 patients with osteosarcoma and measurable disease was 12% at 4 months (95% CI, 6%–19%). There was no significant difference in EFS between the trials according to number of previous treatment regimens or patient age, sex, and ethnicity. One additional phase II trial with a different study design was reported. In this trial, patients with osteosarcoma and metastases to the lung underwent surgical resection of all lung nodules and then were treated with adjuvant inhaled GM-CSF. The 12-month EFS rate for the 42 evaluable patients enrolled in this study was 20% (95% CI, 10%–34%).

Treatment Options Under Clinical Evaluation

Information about National Cancer Institute (NCI)–supported clinical trials can be found on the NCI website. For information about clinical trials sponsored by other organizations, refer to the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

The following are examples of national and/or institutional clinical trials that are currently being conducted:

- APEC1621 (NCT03155620) (Pediatric MATCH: Targeted Therapy Directed by Genetic Testing in Treating Pediatric Patients with Relapsed or Refractory Advanced Solid Tumors, Non-Hodgkin Lymphomas, or Histiocytic Disorders): NCI-COG Pediatric Molecular Analysis for Therapeutic Choice (MATCH), referred to as Pediatric MATCH, will match targeted agents with specific molecular changes identified using a next-generation sequencing targeted assay of more than 4,000 different mutations across more than 160 genes in refractory and recurrent solid tumors. Children and adolescents aged 1 to 21 years are eligible for the trial.

Tumor tissue from progressive or recurrent disease must be available for molecular characterization. Patients with tumors that have molecular variants addressed by treatment arms included in the trial will be offered treatment on Pediatric MATCH. Additional information can be obtained on the NCI website and ClinicalTrials.gov website.

- NCT04154189 (A Study to Compare the Efficacy and Safety of Ifosfamide and Etoposide With or Without Lenvatinib in Children, Adolescents, and Young Adults With Relapsed and Refractory Osteosarcoma): The aim of this study is to evaluate whether lenvatinib in combination with ifosfamide and etoposide (Arm A) is superior to ifosfamide and etoposide (Arm B) in improving the PFS rate at 4 months (by independent imaging review using Response Evaluation Criteria In Solid Tumors [RECIST 1.1]), in children, adolescents, and young adults with relapsed or refractory osteosarcoma.

Current Clinical Trials

Use our advanced clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are now enrolling patients. The search can be narrowed by location of the trial, type of treatment, name of the drug, and other criteria. General information about clinical trials is also available.