White blood cells, or leukocytes (Greek; leucko=white and cyte = cell), are part of the immune system participating in both the innate and humoral immune responses. They circulate in the blood and mount inflammatory and cellular responses to injury or pathogens. White blood cells are part of the body’s immune system. They help the body fight infection and other diseases. Types of white blood cells are granulocytes (neutrophils, eosinophils, and basophils), monocytes, and lymphocytes (T cells and B cells). Checking the number of white blood cells in the blood is usually part of a complete blood cell (CBC) test. It may be used to look for conditions such as infection, inflammation, allergies, and leukemia. Also called leukocyte and WBC.

White blood cells (WBC) are a heterogeneous group of nucleated cells that can be found in circulation for at least a period of their life. Their normal concentration in the blood varies between 4000 and 10,000 per microliter. They play a most important role in phagocytosis and immunity and therefore in defense against infection.

Complete blood count

| Blood component | Abbreviation used | Reference range | SI Reference range |

|---|---|---|---|

| White blood cells | WBC | 4500-11,000/mm3 | 4.5-11.0 x 109/L |

| Red blood cells* | RBC | Male: 4.3-5.9 million/mm3 Female: 3.5-5.5 million/mm3 |

Male: 4.3-5.9 x 1012/L Female: 3.5-5.5 x 1012/L |

| Hemoglobin* | HGB | Male: 13.5-17.5 g/dL Female: 12.0-16.0 g/dL |

Male: 2.09-2.71 mmol/L Female: 1.86-2.48 mmol/L |

| Hematocrit* | HT | Male: 41%-53% Female: 36%-46% |

Male: 0.41-0.53 Female: 0.36-0.46 |

| Mean corpuscular volume | MCV | 80-100 µm3 | 80-100 fl |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin | MCH | 25.4-34.6 pg/cell | 0.39-0.54 fmol/cell |

| Mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration | MCHC | 31%-36% Hb/cell | 4.81-5.58 mmol Hb/L |

| Platelets | Platelets | 150,000-400,000/mm3 | 150-400 x 109/L |

Normal ranges

According to an article in American Family Physician, the normal range (per cubic millimeter) of white blood cells based on age are:

| Age | Normal range |

| Newborn infant | 13,000–38,000 |

| 2-week-old infant | 5,000–20,000 |

| Adult | 4,500–11,000 |

The normal range for pregnant woman in the 3rd trimester is 5,800–13,200 per cubic millimeter.

According to the University of Rochester Medical Center (UMRC), these are the normal ranges of WBCs per microliter of blood (mcL):

| Age range | WBC count (per mcL of blood) |

| newborns | 9,000 to 30,000 |

| children under 2 | 6,200 to 17,000 |

| children over 2 and adults | 5,000 to 10,000 |

These normal ranges can vary by lab. Another common measurement for the volume of blood is cubic millimeter or mm3. A microliter and cubic millimeter equal the same amount. The types of cells that make up WBCs usually fall within a normal percentage of your overall WBC count.

The normal percentages of the types of WBCs in your overall count are usually in these ranges, according to the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (LLS):

| Type of WBC | Normal percentage of overall WBC count |

| neutrophil | 55 to 73 percent |

| lymphocyte | 20 to 40 percent |

| eosinophil | 1 to 4 percent |

| monocyte | 2 to 8 percent |

| basophil | 0.5 to 1 percent |

Higher or lower numbers of WBCs than normal can be a sign of an underlying condition.

Types of WBCs

The different types of white blood cells (leukocytes) include neutrophils, basophils, eosinophils, lymphocytes, monocytes, and macrophages.

White blood cells are much less common than red blood cells. There are five types of white blood cell (leucocyte). These are divided into two main classes

- Granulocytes (includes Neutrophils, Eosinophils and Basophils)

- Agranulocytes (includes Lymphocytes and Monocytes).

Key Points

The two main types of leukocytes are granulocytes and mononuclear leukocytes (agranulocytes).

Leukocytes arise from hemopoietic stem cells in the bone marrow.

Leukocytes are involved in pathogen recognition, phagocytosis (ingestion of particles), pathogen destruction, inflammation mediation, and antigen presentation.

Granulocytes include neutrophils, basophils, eosinophils, and mast cells. Their granules contain enzymes that damage or digest pathogens and release inflammatory mediators into the bloodstream.

Mononuclear leukocytes include lymphocytes, monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. This group is involved in both innate and adaptive immune system functions.

Key Terms

- endocytosed: Engulfed during the process by which the plasma membrane of a cell folds inwards to ingest the material.

- antigen: A substance, usually foreign, that induces an immune response.

- pathogen: Any organism or substance, especially a microorganism, capable of causing disease. Examples include bacteria, viruses, protozoa, or fungi. Microorganisms are not considered pathogenic until the population has grown large enough to cause disease.

White blood cells (WBCs), or leukocytes, are immune system cells that defend the body against infectious disease and foreign materials. There are several different types of WBCs. They share commonalities but are distinct in form and function. WBCs are produced in the bone marrow by hemopoietic stem cells, which differentiate into either lymphoid or myeloid progenitor cells. A major distinguishing feature is the presence of granules; white blood cells are often characterized as granulocytes or agranulocytes.

Structure

Leukocytes can be classified as granulocytes and agranulocytes based on the presence and absence of microscopic granules in their cytoplasm when stained with Giemsa or Leishman stains.

Granulocytes

Neutrophils, basophils, and eosinophils are all granulocytes. These cells also all have azurophilic granules (lysosomes) and specific granules that contain substances unique to each cell’s function. Histologically, granulocytes can be distinguished from one another by the morphology of their nucleus, their size, and how their granules stain.[1]

Neutrophils are 12 to 15 µm in diameter, have multi-lobed nuclei typically consisting of 3 to 5 segments joined by thin strands, or isthmuses. Thus, they are also called polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Neutrophils contain specific granules in the cytoplasm that cannot be resolved by light microscopy and therefore give the cytoplasm a pale pink color. Neutrophils, when activated, migrate into the tissues via diapedesis. These cells have life spans of a few days, and when activated in connective tissue, undergo apoptosis and are then removed by macrophages.

Eosinophils have a bi-lobed nucleus with large cytoplasmic specific granules that are eosinophilic, staining red to pink.

Basophils are 12 to15 µm in diameter, have bi-lobed or S-shaped nuclei, and contain cytoplasmic specific granules (0.5 µm) in diameter that stain blue to purple. The basophilia of the granules is due to the presence of heparin and sulfated glycosaminoglycans. These cells have similar functions as mast cells.

Agranulocytes

Agranulocytes consist of lymphocytes and monocytes, and while they lack specific granules, they do contain azurophilic granules.

Monocytes are precursor cells for the mononuclear phagocytic system, which include cells such as macrophages, osteoclasts, microglial cells in connective tissue and organs. These cells constitute 4 to 8% of white blood cells, are 12 to 15 µm in diameter, have large nuclei that are indented or C- shaped, which can be eccentric. There is abundant cytoplasm, and the lysosomal granules at the resolution of the light microscope give the cytoplasm bluish-gray color.

Lymphocytes constitute approximately 25% white blood cells, are of varying sizes, and have spherical nuclei. The small lymphocytes are similar in size to red blood cells, have spherical heterochromatic nuclei, and scant cytoplasm. Larger lymphocytes, such as activated lymphocytes, have indented nuclei and are 9 to 18 µm in diameter with more cytoplasm containing azurophilic granules. Lymphocytes subdivide into several groups using the cluster of differentiation (CD) markers. The major groups are B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes.

Granulocytes

Granulocytes, also known as polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocytes, are characterized by stained granules within their cytoplasm under a microscope. These granules are membrane-bound enzymes that act primarily in the digestion of endocytosed particles. They may also cause granule-dependent cell-mediated apoptosis through the release of perforins, granzymes, and proteases. The nucleus contains multiple lobes (polymorphonuclear) as opposed to a single rounded lobe. Granulocytes contain toll-like receptors that allow them to recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPS). All categories except neutrophils contain IgE receptors that implicate them in allergic responses. There are four types of granulocytes:

Granulocytes: From left to right, a neutrophil, an eosinophil, and a basophil.

- Neutrophils defend against bacterial or fungal infection and other very small inflammatory processes. They are usually the first responders to microbial infection. Their activity and death in large numbers from degranulation forms purulent necrosis (pus).

- Eosinophils primarily deal with parasitic infections. They are also the predominant inflammatory cells in allergic reactions.

- Basophils are chiefly responsible for short-term inflammatory response (particularly from allergy or irritation) by releasing the chemical histamine, which causes the vasodilation that occurs with inflammation.

- Mast cells function similarly to basophils in that they often mediate inflammation, but are more common and arise from a different hemopoietic lineage.

Mononuclear Leukocytes

Mononuclear (MN) leukocytes are characterized by a single round nucleus within the cytoplasm. Some MN leukocytes contain granules while others do not, but the members of this group are sometimes considered agranulocytes by naming convention. MN leukocytes contain lysosomes, small vesicles containing digestive enzymes that break down foreign matter that is endocytosed by the cell during phagocytosis. The cells include:

- Lymphocytes, which come in three types. B-lymphocytes produce antibodies in the humoral immune response. T-lymphocytes participate in the cell-mediated immune response. NK cells are cytotoxic cells that participate in the innate immune response by killing virally infected and tumor cells and mediating fever and long-lasting inflammation. B and T lymphocytes contain MHC antigen receptors and their activity is antigen-specific. Other leukocytes will attack any pathogen but cannot distinguish between different types of pathogens.

- Monocytes are large leukocytes that differentiate into macrophages and dendritic cells under varying conditions, while performing similar functions in phagocytosis and antigen presentation (the process by which molecular components are presented to lymphocytes to stimulate an adaptive immune response). Monocytes and their progeny contain toll-like receptors and granules.

- Macrophages are monocytes that have migrated out of the blood stream and into the internal body tissues. They destroy necrotic cell debris and foreign material including viruses and bacteria, and can present antigens to naive lymphocytes. They typically arrive at the site of inflammation one to three days after the initial neutrophil response to clean up dead neutrophils, cellular debris, and remaining pathogens.

- Dendritic cells are monocytes that have migrated to cells that are in contact with the external environment, such as the skin, intestines, or respiratory epithelium. Their name comes branched projections called dendrites, which increase their surface area. They phagocytize pathogens and present antigens to naive lymphocytes.

A Macrophage: A macrophage phagocytizes two smaller particles, possibly pathogens

WBC Function

Each type of white blood cell (WBC) has a specific function in defending the body against infections.

Key Points

Leukocyte functions often occur in the bloodstream and may represent either the innate or adaptive immune systems.

Innate immune system functions are non-specific and include phagocytosis, inflammation, and degranulation.

Adaptive immune system functions are antigen-specific and involve antigen presentation as well as cell-mediated and humoral-mediated activities.

Compared to innate immune system functions, adaptive immune system functions take more time to initiate but work much faster. They have a memory component to prevent reinfection by the same pathogen.

Key Terms

- macrophage: A white blood cell that phagocytizes necrotic cell debris and foreign material, including viruses, bacteria, and tattoo ink. It presents foreign antigens on MHC II molecules to lymphocytes. Part of the innate immune system.

- Inflammation: An innate immune system function in response to a pathogen or injury. Chemical mediators cause the blood vessels to dilate and become more permeable, which draws neutrophils to the area.

- cytotoxic: Any mechanism that can cause the death of a cell (typically without phagocytosis), such as degranulation or cell-mediated apoptosis.

Leukocytes ( white blood cells) provide a number of functions that are primarily related to defending the body from pathogens (foreign invaders). Much leukocyte activity takes place within the bloodstream but is not restricted to this area. Many leukocytes are able to perform their functions in tissues or organs during normal transport and in response to injury. Leukocyte functions may be classified as either innate or adaptive based on several characteristics.

Innate Immune System Functions

The innate immune system refers to the body’s ability to prevent pathogen entry and destroy pathogens that do enter the body. Its functions are rapid responses that inhibit a pathogen as soon as it is detected in the body. Innate immune system functions involving leukocytes include:

- Phagocytosis of pathogens. This process is performed primarily by neutrophils, macrophages, and dendritic cells, but most other leukocytes can do it as well. It involves the binding of an Fc receptor to a tail on a pathogen. The pathogen is engulfed by the leukocyte and destroyed with enzymes and free radicals.

- Inflammation. This process is performed primarily by mast cells, eosinophils, basophils, and NK cells. When a pathogen is detected or vascular endothelial cells release stress cytokines from injury such as a cut, leukocytes release a variety of inflammatory cytokines such as histamine or TNF-alpha. These cause vasodilation, increase vascular permeability, and promote neutrophil movement to the inflammation site.

- Degranulation. This process is performed by granulocytes like neutrophils. When pathogens are encountered, granule-dependent apoptosis (a mechanism of cytotoxicity) may be induced in the pathogen by releasing perforins, granzymes, and proteases from their granules.

Neutrophils Phagocytizing Bacteria: Here, neutrophils are depicted phagocytizing and completely engulfing bacteria.

Adaptive Immune System Functions

The adaptive immune system is specific to each pathogen on the basis of antigens, molecular components of pathogens used by leukocytes to recognize that specific pathogen. Compared to the innate immune system, adaptive immune functions work much faster and have a memory component that prevents reinfection by the same pathogen. However, more time typically passes before the adaptive immune system is functional. Adaptive immune functions of leukocytes include:

- Antigen presentation. This process is primarily performed by macrophages and dendritic cells. Following phagocytosis, protein components (antigens) of the pathogen are expressed on leukocyte MHC molecules and presented to naive T cells (and B cells) in the lymph nodes. The T cells will then start the adaptive immune response by rapidly proliferating and differentiating.

- Cell-mediated activities. This process is performed by T cells. Pathogens that bear the T cell’s antigen are destroyed through cytotoxic-induced apoptosis and protease activity.

- Humoral activities. This process is performed by B cells, which secrete antigen-specific antibodies. The antibodies bind to pathogens to opsonize (mark) them for phagocytes to engulf, neutralize, or start a complement cascade in which proteins form a membrane attack complex to lyse the pathogen.

- Memory cell activity. Following antigen presentation, memory B and T cells are created. These rapidly produce new T cells or antibodies if the same pathogen is detected in the future. This prevents that pathogen from reinfecting the organism.

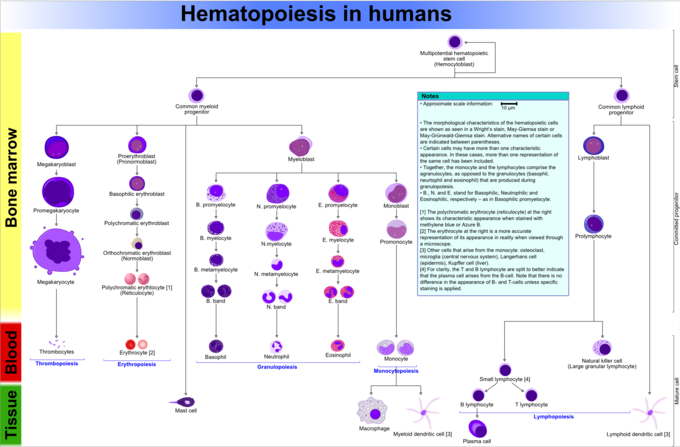

WBC Formation

Hematopoiesis refers to the formation of blood cell components. It is necessary for vertebrate function.

Key Points

Hematopoietic stem cells are self-renewing and reside in the medulla of the bone ( bone marrow ).

All blood cells are divided into two main lineages, produced through lymphoid progenitor cells or myeloid progenitor cells depending on lineage type.

Lymphoid progenitor cells differentiate into B and T cells and NK cells.

Myeloid progenitor cells differentiate into myelocytes (granulocytes and monocytes) or non-leukocytes such as erythrocytes and megakaryocytes (which produce platelets).

Before birth, most blood cell formation occurs in the liver or spleen, which tend to enlarge when used for hematopoiesis. In adults, most blood production occurs in the bone marrow.

Key Terms

- myelocyte: A large cell found in the bone marrow that becomes a granulocyte or monocyte when mature.

- differentiation: The gradual changes that occur when a cell or tissue type changes into a different type. Cells generally become more specialized the more they differentiate and are considered to be terminally differentiated when they cannot differentiate (and often cannot divide) any further.

- megakaryocyte: A large cell found in bone marrow, responsible for the production of platelets.

Hematopoiesis refers to the formation of blood cellular components, including both white and red blood cells. All cellular blood components are derived from hematopoietic stem cells located within the bone marrow. In a healthy adult, approximately 1011–1012 new blood cells are produced daily to maintain equilibrium levels in the peripheral circulation.

Leukocyte Haematopoiesis

Hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs) reside in the bone marrow and have the unique ability to give rise to all mature blood cell types through differentiation into other progenitor cells. HSCs are self-renewing. When they proliferate, at least some daughter cells remain HSCs, so the pool of stem cells does not become depleted over time. The daughters are the myeloid and lymphoid progenitor cells, which cannot self renew but differentiate into various myeloid leukocytes and lymphocytes respectively. This is one of the body’s vital processes.

Leukocyte Lineages

Two different leukocyte lineages and two non-leukocyte lineages arise from the progeny of HSCs. Following this split in differentiation, the subtypes undergo eventual differentiation into terminally-differentiated leukocytes, which typically do not divide independently.

- The lymphocyte lineage derives from common lymphoid progenitor cells, which in turn become lymphoblasts before differentiating into T cells, B cells, and NK cells.

- Myelocytes are an offshoot of common myeloid progenitor cells, which also differentiate into the erythropoietic and magakaryotic progenitors. This diverse group differentiates into granulocytes and monocytes. Monocytes further differentiate into macrophages or dendritic cells upon reaching certain tissues.

- Megakaryocytes (the cells that produce platelets) and erythrocytes (red blood cells) are not formally considered to be leukocytes, but arise from the common myeloid progenitor cells that produce the other cellular components of blood.

Hematopoiesis in Humans: This diagram shows hematopoiesis as it occurs in humans.

Sites of Hematopoiesis in Pre- and Postnatal Periods

In developing embryos, blood formation occurs in aggregates of blood cells in the yolk sac called blood islands. However, most of the blood supply comes from the mother through the placenta. As development progresses, blood formation occurs primarily in the spleen, liver, and lymph nodes.

When bone marrow develops, it eventually assumes the task of forming most of the blood cells for the entire organism. However, maturation, activation, and some proliferation of lymphoid cells occur in lymphoid organs (spleen, thymus, and lymph nodes). In children, hematopoiesis occurs in the marrow of the long bones such as the femur and tibia. In adults, it occurs mainly in the pelvis, cranium, vertebrae, and sternum.

In some cases, the liver, thymus, and spleen may resume their hematopoietic function if necessary. This is called extramedullary hematopoiesis. It may cause these organs to hypertrophy and increase in size substantially. During fetal development, the liver functions as the main haematopoetic organ since bones and marrow develop later. Therefore, the liver is enlarged during development relative to its mature proportions.

Disorders

The two commonly used categories of white blood cell disorders divide them quantitatively into those causing excessive numbers (proliferative disorders) and those causing insufficient numbers (leukopenias).[rx] Leukocytosis is usually healthy (e.g., fighting an infection), but it also may be dysfunctionally proliferative. WBC proliferative disorders can be classed as myeloproliferative and lymphoproliferative. Some are autoimmune, but many are neoplastic.

Another way to categorize disorders of white blood cells is qualitative. There are various disorders in which the number of white blood cells is normal but the cells do not function normally.[rx]

Neoplasia of WBCs can be benign but is often malignant. Of the various tumors of the blood and lymph, cancers of WBCs can be broadly classified as leukemias and lymphomas, although those categories overlap and are often grouped as a pair.

Leucopenias

A range of disorders can cause decreases in white blood cells. This type of white blood cell decreased is usually the neutrophil. In this case the decrease may be called neutropenia or granulocytopenia. Less commonly, a decrease in lymphocytes (called lymphocytopenia or lymphopenia) may be seen.[rx]

Neutropenia

Neutropenia can be acquired or intrinsic.[rx] A decrease in levels of neutrophils on lab tests is due to either decreased production of neutrophils or increased removal from the blood.[rx] The following list of causes is not complete.

- Medications – chemotherapy, sulfates or other antibiotics, phenothiazines, benzodiazepines, antithyroid, anticonvulsants, quinine, quinidine, indomethacin, procainamide, thiazides

- Radiation

- Toxins – alcohol, benzenes

- Intrinsic disorders – Fanconi’s, Kostmann’s, cyclic neutropenia, Chédiak–Higashi

- Immune dysfunction – disorders of collagen, AIDS, rheumatoid arthritis

- Blood cell dysfunction – megaloblastic anemia, myelodysplasia, marrow failure, marrow replacement, acute leukemia

- Any major infection

- Miscellaneous – starvation, hypersplenism

Symptoms of neutropenia are associated with the underlying cause of the decrease in neutrophils. For example, the most common cause of acquired neutropenia is drug-induced, so an individual may have symptoms of medication overdose or toxicity. Treatment is also aimed at the underlying cause of neutropenia.[rx] One severe consequence of neutropenia is that it can increase the risk of infection.[rx]

Lymphocytopenia

Defined as total lymphocyte count below 1.0×109/L, the cells most commonly affected are CD4+ T cells. Like neutropenia, lymphocytopenia may be acquired or intrinsic and there are many causes.[rx] This is not a complete list.

- Inherited immune deficiency – severe combined immunodeficiency, common variable immune deficiency, ataxia-telangiectasia, Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome, immunodeficiency with short-limbed dwarfism, immunodeficiency with thymoma, purine nucleoside phosphorylase deficiency, genetic polymorphism

- Blood cell dysfunction – aplastic anemia

- Infectious diseases – viral (AIDS, SARS, West Nile encephalitis, hepatitis, herpes, measles, others), bacterial (TB, typhoid, pneumonia, rickettsiosis, ehrlichiosis, sepsis), parasitic (acute phase of malaria)

- Medications – chemotherapy (antilymphocyte globulin therapy, alemtuzumab, glucocorticoids)

- Radiation

- Major surgery

- Miscellaneous – ECMO, kidney or bone marrow transplant, hemodialysis, kidney failure, severe burns, celiac disease, severe acute pancreatitis, sarcoidosis, protein-losing enteropathy, strenuous exercise, carcinoma

- Immune dysfunction – arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, myasthenia gravis, systemic vasculitis, Behcet-like syndrome, dermatomyositis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis

- Nutritional/Dietary – alcohol use disorder, zinc deficiency

Like neutropenia, symptoms and treatment of lymphocytopenia are directed at the underlying cause of the change in cell counts.

Proliferative disorders

An increase in the number of white blood cells in circulation is called leukocytosis.[rx] This increase is most commonly caused by inflammation.[rx] There are four major causes: increase of production in bone marrow, increased release from storage in bone marrow, decreased attachment to veins and arteries, decreased uptake by tissues.[rx] Leukocytosis may affect one or more cell lines and can be neutrophilic, eosinophilic, basophilic, monocytosis, or lymphocytosis.

Neutrophilia

Neutrophilia is an increase in the absolute neutrophil count in the peripheral circulation. Normal blood values vary by age.[rx] Neutrophilia can be caused by a direct problem with blood cells (primary disease). It can also occur as a consequence of an underlying disease (secondary). Most cases of neutrophilia are secondary to inflammation.[rx]

Primary causes[rx]

- Conditions with normally functioning neutrophils – hereditary neutrophilia, chronic idiopathic neutrophilia

- Pelger–Huët anomaly

- Down syndrome

- Leukocyte adhesion deficiency

- Familial cold urticaria

- Leukemia (chronic myelogenous (CML)) and other myeloproliferative disorders

- Surgical removal of spleen[rx]

Secondary causes[rx]

- Infection

- Chronic inflammation – especially juvenile rheumatoid arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, Still’s disease, Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, granulomatous infections (for example, tuberculosis), and chronic hepatitis

- Cigarette smoking – occurs in 25–50% of chronic smokers and can last up to 5 years after quitting

- Stress – exercise, surgery, general stress

- Medication-induced – corticosteroids (for example, prednisone, β-agonists, lithium)

- Cancer – either by growth factors secreted by the tumor or invasion of bone marrow by the cancer

- Increased destruction of cells in peripheral circulation can stimulate bone marrow. This can occur in hemolytic anemia and idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura

Eosinophilia

A normal eosinophil count is considered to be less than 0.65×109/L.[rx] Eosinophil counts are higher in newborns and vary with age, time (lower in the morning and higher at night), exercise, environment, and exposure to allergens.[rx] Eosinophilia is never a normal lab finding. Efforts should always be made to discover the underlying cause, though the cause may not always be found.[rx]

References