Anal Cancer/Cancers of the anal canal are rare, comprising approximately 10% of malignancies in the anorectal region, although its incidence has been increasing over the past several decades.[rx][rx] While the traditional approach to treatment was with abdominoperineal resection (APR), this has evolved in the modern era to concurrent chemoradiation as organ-preserving treatment.

Types of Anal Cancer

Several types of tumors may be found in the anus. While some of them are malignant (cancer), others are benign (not cancer) or precancerous (may develop into cancer). The main types of anal cancer are

- Benign tumors – Tumors that are benign are noncancerous tumors. In the anus, this can include polyps, skin tags, granular cell tumors, and genital warts (condylomas).

- Precancerous conditions – This refers to benign tumors that may become malignant over time, which is common in anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) and anal squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (ASIL).

- Squamous cell carcinoma – Squamous cell cancer is the most common type of anal cancer in the United States. According to the American Cancer Society, it accounts for 9 out of 10 cases. These malignant tumors in the anus are caused by abnormal squamous cells (cells that line most of the anal canal).

- Bowen’s disease – This condition, also known as squamous cell carcinoma in situ, is characterized by abnormal cells on anal surface tissue that haven’t invaded deeper layers.

- Basal cell carcinoma – Basal cell carcinoma is a type of skin cancer that generally affects skin exposed to the sun. Because of this, it’s a very rare form of anal cancer.

- Adenocarcinoma – This is a rare form of cancer that arises from the glands surrounding the anus.

- Carcinoma in situ – is early cancer or precancerous cells. They are only on the surface cells of the anal canal. This also may be called Bowen’s disease.

- Squamous cell cancer – (carcinoma) forms in the cells that line the anus. This is the most common type of anal cancer.

- Adenocarcinomas – develop in the glands around the anus.

- Skin cancers, including basal cell and melanoma, often are found when they are in advanced stages.

There are three ways that cancer spreads in the body

Cancer can spread through tissue, the lymph system, and the blood:

- Tissue. The cancer spreads from where it began by growing into nearby areas.

- Lymph system. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the lymph system. The cancer travels through the lymph vessels to other parts of the body.

- Blood. The cancer spreads from where it began by getting into the blood. The cancer travels through the blood vessels to other parts of the body.

Cancer may spread from where it began to other parts of the body

When cancer spreads to another part of the body, it is called metastasis. Cancer cells break away from where they began (the primary tumor) and travel through the lymph system or blood.

- Lymph system – Cancer gets into the lymph system, travels through the lymph vessels, and forms a tumor (metastatic tumor) in another part of the body.

- Blood – Cancer gets into the blood, travels through the blood vessels, and forms a tumor (metastatic tumor) in another part of the body.

The metastatic tumor is the same type of cancer as the primary tumor. For example, if anal cancer spreads to the lung, the cancer cells in the lung are actually anal cancer cells. The disease is metastatic anal cancer, not lung cancer.

Anatomy of Anal Cancer

The anal canal runs from the anal verge (the visible junction between the internal anal canal and hair-bearing keratinized external anal skin) to the anorectal ring (the location in which rectum enters puborectalis sling). The anal canal is approximately 3 to 5 cm in length. The dentate line is the anatomic boundary where mucosa changes from non-keratinized squamous epithelium to colorectal-type columnar mucosa proximally. It divides the upper and lower anal canal. The anal margin, also referred to as perianal skin, is a rim of tissue around the anus encompassed by a 5 cm radius, and it bears true squamous epithelium. Lymphatic drainage of anal cancers depends upon its location relative to the dentate line. Cancers above the dentate line drain to the presacral and internal iliac nodes. Cancers below the dentate line drain to superficial inguinal and femoral nodes.

Causes of Anal Cancer

High grade anal intraepithelial neoplasia (AIN) can be a precursor to anal cancer. AIN can result from an infection with human papillomavirus (HPV), predominantly serotypes 16 and 18. HPV spreads via skin-to-skin contact and sexual intercourse.[rx] Additional risk factors for anal cancer include HIV infection, promiscuous sexual behavior, smoking, chronic immunosuppression not due to HIV, and chronic inflammatory states such as Crohn disease.[rx][rx][rx][rx] HPV vaccines, when given before HPV exposure, reduce the rates of AIN and should be considered in populations at high risk for anal cancer.[rx]

Anal cancer develops when cells grow uncontrollably and form a tumor. Two types of cancer can form in the anus, depending on where the cancer starts.

- Squamous cell cancer – The anal canal connects the rectum to the outside of the body. Squamous cells line the canal. These flat cells look like fish scales under the microscope. Most anal cancers are squamous cell carcinomas because they develop from squamous cells.

- Adenocarcinoma: The point where the anal canal meets the rectum is called the transitional zone. It has squamous cells and glandular cells. Glandular cells produce mucus, which helps the stool pass through the anus smoothly. Adenocarcinoma can also develop from the glandular cells in the anus. Around 3–9% of anal cancers are of this type.

Risk factors

The risk factors for anal cancer include:

- HPV – There is growing evidence that some types of HPV increase the risk of various cancers. Researchers have linked the presence of HPV16 to various cancers, including cervical cancer and some head and neck cancers.

- Other cancers – People who have had another HPV-linked cancer seem to have a higher risk of anal cancer. For females, these include vaginal or cervical cancer, or a history of precancerous cells in the cervix. Males who have had penile cancer have a higher risk, also.

- HIV – People with HIV have a higher risk of developing anal cancer than people without the virus.

- Reduced immunity – People with a suppressed immune system have a higher risk. The immune system can be weaker in people with AIDS and those who take medications following a transplant.

- Sexual activity – Having multiple sex partners can increase the risk, as this increases the chance of exposure to HPV.

- Sex – Anal cancer is more common in females than in males. However, among African Americans, it is more common among males up to the age of 60 years, after which it is more likely to affect females.

- Age – As people get older, their chances of developing anal cancer increase.

- Smoking – Smokers have a significantly higher risk of several cancers, including anal cancer. Quitting may lower the risk.

Symptoms of Anal Cancer

- Bleeding from anus/rectum, especially during bowel movements.

- Having a lump or pain in the area.

- Itching (also known as pruritus).

- Seeing a change in bowel movements, such as frequency or consistency of the stools.

- Leaking stool.

- Feeling like you constantly need to have a bowel movement.

- bleeding from the bottom (rectal bleeding)

- itching and pain around the anus

- small lumps around the anus

- a discharge of mucus from the anus

- loss of bowel control (bowel incontinence)

- Bleeding from the anus

- Pain or pressure in your anal area

- Itching around your anus

- Fluid leaking from your anus

- Narrower stools or other changes in your bowel movements

- A lump or swelling near your anus

- Swollen lymph nodes in your anal or groin area

Diagnosis of Anal Cancer

Clinical presentation can include bleeding (45%), pain (30%), pruritus, perianal mass, fecal urgency, or change in the stool caliber.[rx] Locally advanced tumors may have the above symptoms as well as mucous discharge, lower extremity edema, or non-healing perianal wounds. Systemic metastasis of squamous cell anal cancer occurs in less than 10% of cases at presentation.[rx] The liver and lungs are the most common site of distant spread, and clinical presentation of metastatic disease is dependent upon location and tumor burden.

- Physical exam and health history – An exam of the body to check general signs of health, including checking for signs of disease, such as lumps or anything else that seems unusual. A history of the patient’s health habits and past illnesses and treatments will also be taken.

- Digital rectal examination (DRE) – An exam of the anus and rectum. The doctor or nurse inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into the lower part of the rectum to feel for lumps or anything else that seems unusual.

- Anoscopy – An exam of the anus and lower rectum using a short, lighted tube called an anoscope.

- Proctoscopy – A procedure to look inside the rectum and anus to check for abnormal areas, using a proctoscope. A proctoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing the inside of the rectum and anus. It may also have a tool to remove tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

- Endo-anal or endorectal ultrasound – A procedure in which an ultrasound transducer (probe) is inserted into the anus or rectum and used to bounce high-energy sound waves (ultrasound) off internal tissues or organs and make echoes. The echoes form a picture of body tissues called a sonogram.

- Biopsy – The removal of cells or tissues so they can be viewed under a microscope by a pathologist to check for signs of cancer. If an abnormal area is seen during the anoscopy, a biopsy may be done at that time.

- Anal electromyography (EMG) – This test determines if nerve damage is the reason why the anal sphincters are not working properly. It also examines the coordination between the rectum and anal muscles.

- Anal manometry – This test studies the strength of the anal sphincter muscles. A short, thin tube, inserted up into the anus and rectum, is used to measure the sphincter tightness.

- Anal ultrasound – This test helps evaluate the shape and structure of the anal sphincter muscles and surrounding tissue. In this test, a small probe is inserted up into the anus and rectum to take images of the sphincters.

- Pudendal nerve terminal motor latency test – This test measures the function of the pudendal nerves, which are involved in bowel control.

- Proctography (also called defecography) – This test is done in the radiology department. In this test, an X-ray video is taken that shows how well the rectum is functioning. The video shows how much stool the rectum can hold, how well the rectum holds the stool, and how well the rectum releases the stool.

- Colonoscopy – A procedure to look inside the rectum and colon for polyps (small pieces of bulging tissue), abnormal areas, or cancer. A colonoscope is a thin, tube-like instrument with a light and a lens for viewing. It may also have a tool to remove polyps or tissue samples, which are checked under a microscope for signs of cancer.

- Reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT–PCR) test – A laboratory test in which the amount of a genetic substance called mRNA made by a specific gene is measured. An enzyme called reverse transcriptase is used to convert a specific piece of RNA into a matching piece of DNA, which can be amplified (made in large numbers) by another enzyme called DNA polymerase. The amplified DNA copies help tell whether a specific mRNA is being made by a gene. RT–PCR can be used to check the activation of certain genes that may indicate the presence of rectal prolapse cells. This test may be used to look for certain changes in a gene or chromosome, which may help diagnose rectal prolapse.

- Immunohistochemistry – A laboratory test that uses antibodies to check for certain antigens (markers) in a sample of a patient’s tissue. The antibodies are usually linked to an enzyme or a fluorescent dye. After the antibodies bind to a specific antigen in the tissue sample, the enzyme or dye is activated, and the antigen can then be seen under a microscope. This type of test is used to help diagnose cancer and to help tell one type of cancer from another type of cancer.

- Carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) assay – A test that measures the level of CEA in the blood. CEA is released into the bloodstream from both rectal prolapse and normal cells. When found in higher than normal amounts, it can be a sign of rectal prolapse or other conditions.

- Anorectal manometry – measures and assesses the anal sphincter (internal and external) and rectal pressure and its function. This method is used to evaluate patients with fecal incontinence and constipation. It can directly measure the luminal pressure, including the high-pressure zone, resting pressure, squeezing pressure, rectal sensation/compliance, and the anorectal inhibitory reflex.[rx]

- Defecating proctography/Defecography – A study using X-ray imaging to evaluate anatomic defects of the anorectal region and function of the puborectalis muscle. A contrast filled paste gets initially introduced to the rectum, and the patient is instructed to defecate in a series of stages (relaxation, contraction, tensing of the abdomen, and evacuation).[rx]

- Balloon capacity and compliance test – Evaluates the function of the rectum using a device (plastic catheter with a latex balloon attached), which is inserted into the rectum and gradually filled with warm water. During this process, the volume and pressure are measured.[rx]

- Balloon evacuation study – This test is similar to the balloon capacity and compliance test in which a catheter with a small balloon gets inserted into the rectum and filled with water. Different volumes of water get loaded inside the balloon, and the patient is instructed to evacuate the balloon. This procedure is done to evaluate the opening of the anal canal and to assess the relaxation of the pelvic floor.[rx]

- Pudendal nerve terminal motor latency – A probe designed to stimulate and record nerve activity is placed on the physician’s gloved finger, which is then inserted into the rectum to measure pudendal nerve activity (latency to contraction of the anal sphincter muscle). The pudendal nerve innervates the anal sphincter muscles; therefore, this test can be used to assess any injury to that nerve.

- Electromyography – A test to measure the ability of the puborectalis muscle and sphincter muscles to relax properly. An electrode is placed inside the rectum, and the activity of these muscles gets evaluated throughout a series of stages (relaxation, contraction, and evacuation).[rx]

- Endoanal Ultrasonography – The use of ultrasound imaging to examine rectal lesions, defects, or injuries to the surrounding tissues.[rx]

- Suction rectal biopsy – Gold standard for the diagnosis of Hirschsprung disease. A biopsy is taken two cm above the dentate line, and the absence of ganglion cells on histology confirms the diagnosis. Hypertrophic nerve fibers may be present in addition to this finding.[rx]

- Contrast enema – Used as one of the diagnostic methods for Hirschsprung disease. Useful for localization of the aganglionic segment by looking for a narrowed rectum. Diagnostic confirmation is via a rectal biopsy.[rx]

- CT scan (CAT scan) – A procedure that makes a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body, such as the abdomen, pelvis, or chest, taken from different angles. The pictures are made by a computer linked to an x-ray machine. A dye may be injected into a vein or swallowed to help the organs or tissues show up more clearly. This procedure is also called computed tomography, computerized tomography, or computerized axial tomography.

- Chest x-ray – An x-ray of the organs and bones inside the chest. An x-ray is a type of energy beam that can go through the body and onto film, making a picture of areas inside the body.

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) – A procedure that uses a magnet, radio waves, and a computer to make a series of detailed pictures of areas inside the body. This procedure is also called nuclear magnetic resonance imaging (NMRI).

- PET scan (positron emission tomography scan) – A procedure to find malignant tumor cells in the body. A small amount of radioactive glucose (sugar) is injected into a vein. The PET scanner rotates around the body and makes a picture of where glucose is being used in the body. Malignant tumor cells show up brighter in the picture because they are more active and take up more glucose than normal cells do.

- Pelvic exam – An exam of the vagina, cervix, uterus, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and rectum. A speculum is inserted into the vagina and the doctor or nurse looks at the vagina and cervix for signs of disease. A Pap test of the cervix is usually done. The doctor or nurse also inserts one or two lubricated, gloved fingers of one hand into the vagina and places the other hand over the lower abdomen to feel the size, shape, and position of the uterus and ovaries. The doctor or nurse also inserts a lubricated, gloved finger into the rectum to feel for lumps or abnormal areas.

Treatment of Anal Cancer

- Activity – Typically, the child is encouraged to walk around as soon as possible.

- Diet – Patients are started on liquids after their surgery then advanced to a general diet.

- Antibiotics – To help prevent or treat an infection caused by bacteria.

- Anti-nausea medicine – To control vomiting (throwing up).

- Pain medicine – Pain medicine can include acetaminophen (Tylenol®), ibuprofen (Motrin®), or narcotics. These medicines can be given by vein or by mouth.

- Stool softeners – Polyethylene glycol (Miralax), Docusate (Colace) or senna are among the medications used to avoid straining after surgery.

Certain factors affect the prognosis (chance of recovery) and treatment options.

The prognosis depends on the following:

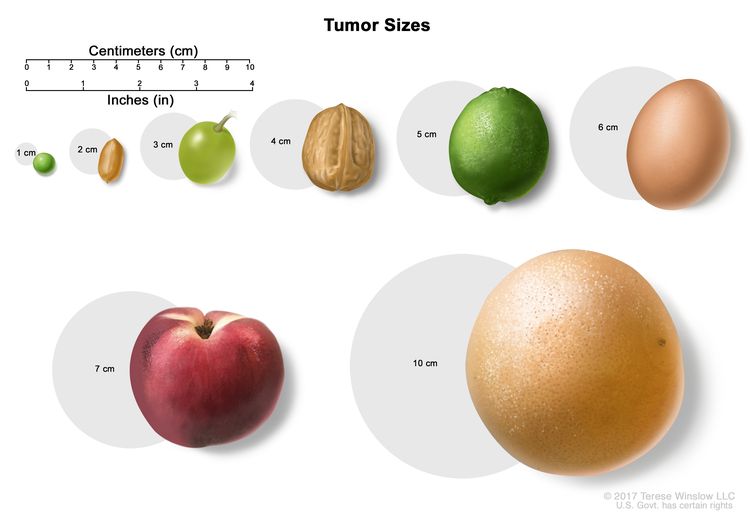

- The size of the tumor.

- Whether the cancer has spread to the lymph nodes.

The treatment options depend on the following:

- The stage of the cancer.

- Where the tumor is in the anus.

- Whether the patient has human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

- Whether cancer remains after initial treatment or has recurred.

Stages of Anal Cancer

KEY POINTS

- After anal cancer has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer cells have spread within the anus or to other parts of the body.

- There are three ways that cancer spreads in the body.

- Cancer may spread from where it began to other parts of the body.

- The following stages are used for anal cancer:

- Stage 0

- Stage I

- Stage II

- Stage III

- Stage IV

- Anal cancer can recur (come back) after it has been treated.

After anal cancer has been diagnosed, tests are done to find out if cancer cells have spread within the anus or to other parts of the body.

The process used to find out if cancer has spread within the anus or to other parts of the body is called staging. The information gathered from this staging process determines the stage of the disease. It is important to know the stage in order to plan treatment. The following tests may be used in the staging process:

The following stages are used for anal cancer:

Stage 0

In stage 0, abnormal cells are found in the mucosa (innermost layer) of the anus. These abnormal cells may become cancer and spread into nearby normal tissue. Stage 0 is also called high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL).

Stage I

In stage I, cancer has formed and the tumor is 2 centimeters or smaller.

Stage II

Stage II anal cancer is divided into stages IIA and IIB.

- In stage IIA, the tumor is larger than 2 centimeters but not larger than 5 centimeters.

- In stage IIB, the tumor is larger than 5 centimeters.

Stage III

Stage III anal cancer is divided into stages IIIA, IIIB, and IIIC.

- In stage IIIA, the tumor is 5 centimeters or smaller and has spread to lymph nodes near the anus or groin.

- In stage IIIB, the tumor is any size and has spread to nearby organs, such as the vagina, urethra, or bladder. Cancer has not spread to lymph nodes.

- In stage IIIC, the tumor is any size and may have spread to nearby organs. Cancer has spread to lymph nodes near the anus or groin.

Stage IV

In stage IV, the tumor is any size. Cancer may have spread to lymph nodes or nearby organs and has spread to other parts of the body, such as the liver or lungs.

Anal cancer can recur (come back) after it has been treated.

- The cancer may come back in the anus or other parts of the body, such as the liver or lungs.

Treatment of Anal Cancer

- There are different types of treatment for patients with anal cancer.

- Three types of standard treatment are used:

- Surgery

- Radiation therapy

- Chemotherapy

- New types of treatment are being tested in clinical trials.

- Radiosensitizers

- Immunotherapy

- Treatment for anal cancer may cause side effects.

- Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial.

- Patients can enter clinical trials before, during, or after starting their cancer treatment.

- Follow-up tests may be needed.

There are different types of treatment for patients with anal cancer.

Different types of treatments are available for patients with anal cancer. Some treatments are standard (the currently used treatment), and some are being tested in clinical trials. A treatment clinical trial is a research study meant to help improve current treatments or obtain information on new treatments for patients with cancer. When clinical trials show that a new treatment is better than the standard treatment, the new treatment may become the standard treatment. Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial. Some clinical trials are open only to patients who have not started treatment.

Three types of standard treatment are used:

Surgery

- Local resection – A surgical procedure in which the tumor is cut from the anus along with some of the healthy tissue around it. Local resection may be used if the cancer is small and has not spread. This procedure may save the sphincter muscles so the patient can still control bowel movements. Tumors that form in the lower part of the anus can often be removed with local resection.

- Abdominoperineal resection – A surgical procedure in which the anus, the rectum, and part of the sigmoid colon are removed through an incision made in the abdomen. The doctor sews the end of the intestine to an opening, called a stoma, made in the surface of the abdomen so body waste can be collected in a disposable bag outside of the body. This is called a colostomy. Lymph nodes that contain cancer may also be removed during this operation. This procedure is used only for cancer that remains or comes back after treatment with radiation therapy and chemotherapy.

Resection of the colon with colostomy. Part of the colon containing the cancer and nearby healthy tissue are removed, a stoma is created, and a colostomy bag is attached to the stoma.

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy is a cancer treatment that uses high-energy x-rays or other types of radiation to kill cancer cells or keep them from growing. There are two types of radiation therapy:

- External radiation therapy uses a machine outside the body to send radiation toward the area of the body with cancer.

- Internal radiation therapy uses a radioactive substance sealed in needles, seeds, wires, or catheters that are placed directly into or near the cancer.

The way the radiation therapy is given depends on the type and stage of the cancer being treated. External and internal radiation therapy are used to treat anal cancer.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is a cancer treatment that uses drugs to stop the growth of cancer cells, either by killing the cells or by stopping the cells from dividing. When chemotherapy is taken by mouth or injected into a vein or muscle, the drugs enter the bloodstream and can reach cancer cells throughout the body (systemic chemotherapy).

New types of treatment are being tested in clinical trials.

This summary section describes treatments that are being studied in clinical trials. It may not mention every new treatment being studied. Information about clinical trials is available from the NCI website.

Radiosensitizers

Radiosensitizers are drugs that make tumor cells more sensitive to radiation therapy. Combining radiation therapy with radiosensitizers may kill more tumor cells.

Immunotherapy

Immunotherapy is a treatment that uses the patient’s immune system to fight cancer. Substances made by the body or made in a laboratory are used to boost, direct, or restore the body’s natural defenses against cancer. This type of cancer treatment is also called biotherapy or biologic therapy.

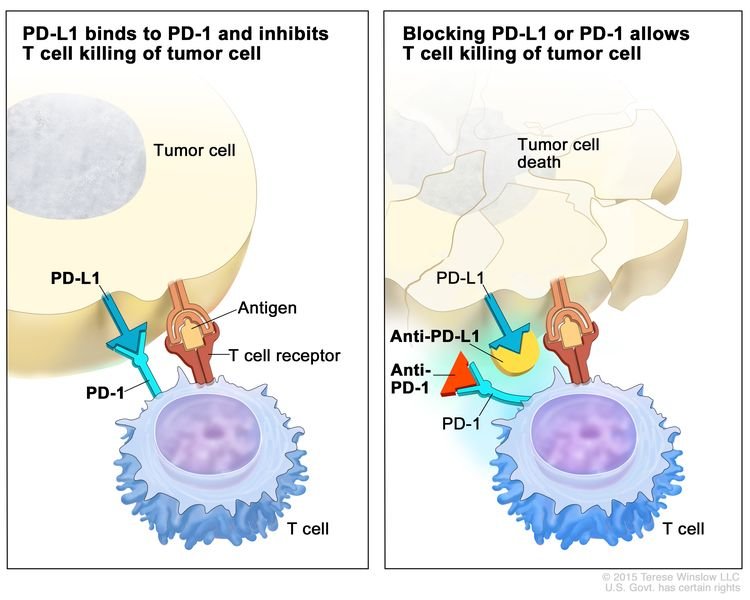

Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy is a type of immunotherapy.

- Immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy: PD-1 is a protein on the surface of T cells that helps keep the body’s immune responses in check. When PD-1 attaches to another protein called PDL-1 on a cancer cell, it stops the T cell from killing the cancer cell. PD-1 inhibitors attach to PDL-1 and allow the T cells to kill cancer cells. Pembrolizumab and nivolumab are types of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

Immune checkpoint inhibitor. Checkpoint proteins, such as PD-L1 on tumor cells and PD-1 on T cells, help keep immune responses in check. The binding of PD-L1 to PD-1 keeps T cells from killing tumor cells in the body (left panel). Blocking the binding of PD-L1 to PD-1 with an immune checkpoint inhibitor (anti-PD-L1 or anti-PD-1) allows the T cells to kill tumor cells (right panel).

Immunotherapy uses the body’s immune system to fight cancer. This animation explains one type of immunotherapy that uses immune checkpoint inhibitors to treat cancer.

Treatment for anal cancer may cause side effects.

For information about side effects caused by treatment for cancer, see our Side Effects page.

Patients may want to think about taking part in a clinical trial.

For some patients, taking part in a clinical trial may be the best treatment choice. Clinical trials are part of the cancer research process. Clinical trials are done to find out if new cancer treatments are safe and effective or better than the standard treatment.

Many of today’s standard treatments for cancer are based on earlier clinical trials. Patients who take part in a clinical trial may receive the standard treatment or be among the first to receive a new treatment.

Patients who take part in clinical trials also help improve the way cancer will be treated in the future. Even when clinical trials do not lead to effective new treatments, they often answer important questions and help move research forward.

Patients can enter clinical trials before, during, or after starting their cancer treatment.

Some clinical trials only include patients who have not yet received treatment. Other trials test treatments for patients whose cancer has not gotten better. There are also clinical trials that test new ways to stop cancer from recurring (coming back) or reduce the side effects of cancer treatment.

Clinical trials are taking place in many parts of the country. Information about clinical trials supported by NCI can be found on NCI’s clinical trials search webpage. Clinical trials supported by other organizations can be found on the ClinicalTrials.gov website.

Treatment of Stage 0 (Carcinoma in Situ)

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment of stage 0 is usually local resection.

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done.

Treatment of Stages I, II, and III Anal Cancer

For information about the treatments listed below,

Treatment of stage I, stage II, and stage III anal cancer may include the following:

- Local resection for tumors of the skin around the outside of the anus and tumors inside the anal opening that do not involve the anal sphincter.

- External-beam radiation therapy with chemotherapy.

- Radiation therapy alone.

- Abdominoperineal resection, if cancer remains or comes back after treatment with radiation therapy and chemotherapy. Other options may include treatment with additional chemoradiation therapy, chemotherapy alone, or immunotherapy.

Patients who have had treatment that saves the sphincter muscles may receive follow-up exams every 3 months for the first 2 years, including rectal exams with endoscopy and biopsy, as needed to check for recurrence.

Use our clinical trial search to find NCI-supported cancer clinical trials that are accepting patients. You can search for trials based on the type of cancer, the age of the patient, and where the trials are being done. General information about clinical trials is also available.

Treatment of Stage IV Anal Cancer

For information about the treatments listed below, see the Treatment Option Overview section.

Treatment of stage IV anal cancer may include the following:

- Palliative surgery to relieve symptoms and improve the quality of life.

- Palliative radiation therapy.

- Palliative chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy.

- A clinical trial of immune checkpoint inhibitors.

- A clinical trial of new treatment options.

Tumors of the Anal Margin

Anal margin cancers are more commonly diagnosed at an earlier stage and therefore tend to have a better prognosis. Management of very early stage anal margin cancer is best by wide local excision or radiotherapy alone, similar to management of skin cancer.[rx] The recommended radiation dose in these cases is between 60 to 65 Gy in 6 to 7 weeks. More advanced disease of the anal margin is treated similarly to anal canal cancers.

Tumors of the Anal Canal

The traditional management of tumors of the anal canal was via an abdominoperineal resection (APR) resulting in a permanent colostomy. Since the 1980s, there has been a paradigm shift for nonsurgical organ-preserving treatment, and modern management consists of concurrent chemoradiation. While there are no randomized trials comparing APR with chemoradiation, superior colostomy-free survival rates with equivalent survival have established chemoradiation as the preferred modality of treatment.[rx] Current radiation techniques involve intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) to a minimum dose of 45 Gy via conventional fractionation. Concurrent chemotherapy includes a combination of mitomycin C (MMC), 5FU, capecitabine, or cisplatin.

Suitability for Definitive Treatment

Performance status must be a consideration when determining a patient’s suitability for definitive treatment. Poor performance status may preclude adherence to conventional chemoradiation. Upfront APR may also be indicated if the patient has bowel incontinence or fistula present at baseline. Other relative reasons that may preclude definitive treatment include prior pelvic radiotherapy or surgery and any underlying medical, psychiatric, and/or social concerns.[rx]

HIV/AIDS Patients

People living with HIV have a 15 to 35-fold increase in anal cancer incidence.[rx] There is evidence that they have higher local relapse rates and higher rates of acute skin toxicity although there are no observable differences in complete response rates or 5-year OS.[rx] HIV-positive patients should continue on antiretroviral therapy throughout chemoradiation. Patients living with HIV should also be evaluated by their CD4 count, making appropriate chemotherapy adjustments to limit hematologic toxicity. Although concerns for increased hematological toxicity may exist in the HIV positive patient, standard MMC/ 5FU is the preferred chemotherapeutic regimen with superior outcomes when compared to cisplatin-based chemotherapy. In the setting of poorly controlled HIV with high viral load, >10000 copies, or very low CD4 count with significant concerns for hematologic toxicity, cisplatin-based chemotherapy is acceptable.

Surgical Oncology

Historically, APR was the standard of care for anal cancers, resulting in permanent colostomies. General principles for APR are similar to those of distal rectal cancer, which incorporate meticulous total mesorectal excision (TME) and removal of the distal colon, rectum, and anal sphincter complex using both anterior abdominal and perineal incisions. APR alone yields a poor 5-year overall survival rate of 50% and local recurrence rates of 30%.[rx] In an effort to reduce the rates of local recurrence, Nigro et al.[rx] pioneered a neoadjuvant regimen consisting of chemotherapy and radiation. In his report of 28 patients, 80% experienced a complete pathologic response. These promising results led to multiple randomized clinical trials of anal cancer to validate definitive chemoradiation as primary treatment of anal cancer. Therefore, the role of APR in the modern era is predominantly reserved for salvage treatment or patients with dysfunctional anal sphincter at diagnosis. Adenocarcinomas of the anal canal may also receive treatment with organ preservation.[rx]

Local excision with wide margins may be an alternative to chemoradiation in select patients with T1N0M0 anal canal cancers, as long as sphincter function can is preservable. However, the cure rates are markedly lower: 60% at 5 years, with local recurrence rates of 40%.[rx][rx] Therefore, local excision alone should be reserved for unique circumstances such as a patient with poor performance status and/or significant comorbidities.[rx]

Radiation Oncology

Radiation Alone

The efficacy of external beam radiation therapy (EBRT) alone in patients with anal cancer has undergone extensive study. In Taboul et al.,[rx] local control for primary tumors < 4 cm was 90% at 10 years, whereas it was 65% for primary tumors > 4 cm. Overall, 57% of patients maintained normal anal function. Newmen et al.[rx] reported similar results for radiation alone, in which they found that the probability of local control was related to the T stage. Overall, 74% of patients maintained a functional anus. Very few studies have reported on the efficacy of brachytherapy alone. James et al.[rx] used interstitial radiotherapy as primary treatment and found a 64% local control for tumors < 5 cm diameter at presentation.

Radiation Alone vs. Chemoradiation

After the Nigro protocol demonstrated a high rate of complete pathologic response to neoadjuvant chemoradiation, there was the development of multiple randomized clinical trials to validate definitive chemoradiation as primary treatment of anal cancer. Concurrent chemotherapy and radiation yield results superior to those of radiation alone or surgery alone. The two most prominent trials comparing radiation alone to chemoradiation include ACT I and EORTC 22861. The ACT I trial randomized patients to radiation alone vs. chemoradiation with 5FU/MMC. Results indicated improved 3-yr local control with chemoradiation vs radiation alone (64% vs 41%, p < 0.001).[rx] A recently published follow-up study on these patients demonstrates a persistent local control benefit after 13 years, with an absolute risk of locoregional recurrence reduced by 25%.[rx] Their results were similar to EORTC 22896, with the same randomization, which showed a 5-yr local control improvement from 50% to 68% (p = 0.02) with chemoradiation. Similarly, patients had an improved colostomy-free survival rate with chemoradiation.[rx]

Radiation Dose and Technique

The optimal dose and fractionation of radiation have yet to be fully elucidated. A minimum dose of at least 45 Gy is the current recommendation. One study showed that T1 lesions had effective treatment with a dose of 50 to 60 Gy.[rx] Several studies suggest that dose escalation results in higher local control rates.[rx][rx] However, the ACCORD 03 trial did not see a benefit in colostomy-free survival or complete response with higher boost doses of radiation up to 70 Gy.[rx] Therefore, conventional doses between 50.4 to 59.4 Gy are acceptable reserving doses at the higher end of the spectrum for bulkier disease.

Techniques associated with radiation therapy have evolved with the utilization of intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT). This inverse planning method of external beam radiotherapy (EBRT) increases the therapeutic ratio by increasing conformal dose to the target structures while reducing dose to surrounding normal tissue.[rx] IMRT is clinically associated with decreased acute toxicity when compared to historical outcomes. RTOG 0529 is a phase II study evaluating patients with anal cancer treated with IMRT chemoradiation. T2N0 patients received treatment with a simultaneous integrated boost (SIB) plan prescribing 50.4 Gy to the primary tumor and 42 Gy to elective nodes in 28 fractions. T3-4N0 patients received treatment with a SIB plan delivering 54 Gy to the primary tumor and 45 Gy to elective nodes in 30 fractions. Positive nodes < 3 cm were treated to 50.4 Gy in 30 fractions, whereas nodes >=3cm were treated to 54 Gy in the same 30 fractions. Although the primary endpoint, reducing grade 2+ acute GI/GU toxicity by 15% compared to RTOG 9811, was not met, there was significant sparing of grade 2+ hematologic and grade 3+ dermatologic and GI toxicity.[rx] It is important to note that quality control and technical aspects of IMRT are challenging and conformal radiation therapy requires training in target volume contouring as demonstrated in RTOG 0529 by the number of plans failing central review. Various contouring atlases are available, including RTOG 0529, Myerson et al., and Ng et al.[rx][rx][rx]

Dose Constraints

The main purpose of dose constraints is to limit the acute and long-term toxicities associated with radiation to the pelvis when using IMRT. RTOG 0529 limited small and large bowel to V45 Gy < 20 cc, V35 Gy < 150 cc, and V30 Gy < 200 cc. This resulted in acute grade 2+ GI adverse events of 73% and acute grade 3+ GI adverse events of 21%. The same study limited bladder dose to V50 Gy <= 5%, V40 Gy <= 35%, and V35 Gy <= 50%. These constraints limited acute grade 2+ GU adverse events to 15% and acute grade 3+ GU adverse events to 2%.[rx] The overall rate of late GI grade 2+ adverse events was 10% and late GU grade 2+ adverse events was 4%.[rx]

Nodal Metastases

Lymph node positivity portends a poor prognosis and correlates with worse survival and colostomy rates.[rx] Radiation alone controls 70% of involved inguinal nodes, whereas chemoradiation controls 90% of involved inguinal nodes.[rx] Therefore, it is important to include mesenteric, iliac, and inguinal lymph nodes within the radiation fields.[rx][rx][rx]

Salvage Treatment

Despite the effectiveness of chemoradiation as definitive management, reports exist of locoregional failure rates of 10 to 30%.[rx][rx] Progressive or recurrent disease after definitive chemoradiation requires APR for salvage. Mullen et a.l[37] reported an actuarial 5-yr survival rate of 64% in 31 patients after radical salvage surgery. This study also showed that dose > 55 Gy as part of the initial chemoradiation regimen results in a better prognosis after radical salvage surgery.

Medical Oncology

MMC

RTOG 87-04 demonstrated a benefit to chemoradiation with MMC and 5FU vs. chemoradiation with 5FU alone.[rx] This study showed an improvement in 5-yr LC from 64% to 83% as well as a decreased colostomy rate from 22% to 9% (p = 0.002) with the addition of MMC.

Capecitabine

Capecitabine is an acceptable alternative to 5FU in the treatment of colon and rectal cancer with fewer hematologic toxicities, and it has therefore merited consideration as an alternative to 5FU in chemoradiation regimens for anal cancer. Although data for this regimen are limited, multiple retrospective studies have shown adequate LC, OS, and colostomy-free survival with this group of patients.[rx][rx]

Cisplatin

Cisplatin as a substitute for MMC has undergone evaluation in multiple phase II studies showing promising results for chemoradiation with 5FU and cisplatin.[rx][rx] Fewer hematologic and other toxicities are evident with cisplatin relative to MMC. The ACT II trial compared cisplatin with MMC and looked at the effect of additional maintenance chemotherapy following definitive chemoradiation. In this study, patients were randomly assigned to 5FU/MMC or 5FU/cisplatin with 50.4 Gy concurrent radiation. Each patient then underwent a second randomization receiving two cycles of maintenance therapy with 5FU and cisplatin vs. no maintenance therapy. There was no difference among any arm of the study, and because it was not a non-inferiority trial, they concluded that 5FU and MMC should remain the standard of care.[rx] Also, this trial confirmed that assessment for treatment response should not commence prior to 26 weeks unless there is a clear progression of the disease.[rx] RTOG 9811 was a two-arm trial evaluating the utilization of cisplatin as a replacement for MMC. Induction cisplatin plus concurrent chemoradiation with cisplatin/5FU was compared to the standard of concurrent chemoradiation with 5FU/MMC. Results were inferior in the cisplatin/5FU arm as compared to standard chemoradiation with 5FU/MMC.[rx] The use of induction cisplatin in this study may have confounded the results, because of the delay in the completion of therapy. The cisplatin arm resulted in worse 5-yr OS (70.7% vs 78.3%, p = 0.026), DFS (57.8% vs 67.8%, p = 0.006), and colostomy-free survival (65% vs 71.9%, p = 0.05) compared to the MMC arm.[rx] Chemoradiation with trimodal therapy including 5FU, MMC, and cisplatin was studied in a phase II trial, but found to be too toxic.[rx] Taken together, these studies support 5FU and MMC remaining the standard of care in concurrent chemoradiation with the possibility of using 5FU/cisplatin in the rare patient at high risk for excessive hematologic toxicity from MMC.

Induction

According to ACCORD 03, induction chemotherapy with 5FU and cisplatin offers no benefit in survival, complete response, or colostomy-free survival.[rx] This trial had two randomizations, one that looked at higher boost doses of radiation (as discussed previously), and the other evaluated two cycles of induction chemotherapy with 5FU/cisplatin vs. no induction chemotherapy. Additionally, RTOG 9811 as discussed above, demonstrated a detriment in OS, DFS, and colostomy-free survival with induction cisplatin.[rx]

Metastatic

First-line treatment of metastatic anal cancer includes a fluoropyrimidine-based regimen plus cisplatin. Additional regimens may include carboplatin plus paclitaxel or mFOLFOX. Second-line systemic therapies may include the anti-PD-1 antibody nivolumab, which has a 17% response rate in the KEYNOTE-028 study.[rx] Palliative radiation should be a consideration for symptomatic metastases, and chemoradiation may be an option for local control of bulky primary disease

Staging

Several clinical staging systems have been used in the past. The TNM (tumor, nodes, metastases) classification system developed by the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) is the most widely accepted classification system. TNM staging may use a combination of physical examination, positron emission tomography (PET), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and/or computed tomography (CT) to identify the primary tumor, involved nodes, and metastatic disease if present.[rx] If there is discordant or indeterminate imaging, pathologic staging with a sentinel lymph node biopsy may be an option.[rx] Unlike other GI malignancies, anal cancer T-stage is based primarily on tumor size rather than depth of invasion. A major change in the revision from AJCC 7th to 8th edition staging is with nodal staging. Previously lymph node staging was denoted as N1, N2, or N3 based on the location of regional nodes, which has undergone revision to a more straightforward N0-N1 designation based on the presence of lymph nodes. The N1 category now subdivides into N1a, N1b, and N1c based on the location of the nodes. This change is due to long-term outcomes of RTOG 98-11, demonstrating overall survival is impacted primarily by nodal positivity rather than the location of regional nodes.[rx]

AJCC 8th Edition:

Primary Tumor (T)

-

TX: Primary tumor not assessed

-

T0: No evidence of primary tumor

-

Tis: High-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

-

T1: Tumor 2 cm or less

-

T2: Tumor more than 2 cm but not more than 5 cm

-

T3: Tumor more than 5 cm

-

T4: Tumor of any size that invades adjacent organ(s) including vagina, urethra, or bladder

Regional Lymph Nodes (N)

-

NX: Regional lymph nodes cannot be assessed

-

N0: No regional lymph node metastasis

-

N1: Regional lymph node metastasis present

-

N1a: Metastasis in inguinal, mesorectal, or internal iliac lymph nodes

-

N1b: Metastasis in external iliac lymph nodes

-

N1c: Metastasis in external iliac with any N1a nodes

Distant Metastasis (M)

-

M0: No distant metastasis

-

M1: Distant Metastasis

Anatomic Stage/Prognostic Groups:

-

Stage 0: Tis N0 M0

-

Stage I: T1 N0 M0

-

Stage IIA: T2 N0 M0

-

Stage IIB: T3 N0 M0

-

Stage IIIA: T1-2 N1 M0

-

Stage IIIB: T4 N0 M0

-

Stage IIIC: T3-4 N1 M0

-

Stage IV: Any T Any N M1

The following are risk factors for anal cancer:

Anal HPV infection

Being infected with human papillomavirus (HPV) is the main risk factor for anal cancer. Being infected with HPV can lead to squamous cell carcinoma of the anus, the most common type of anal cancer. About nine out of every ten cases of anal cancer are found in patients with anal HPV infection.

Patients with healthy immune systems are usually able to fight HPV infections. Patients with weakened immune systems who are infected with HPV have a higher risk of anal cancer.

Certain medical conditions

History of cervical, vaginal, or vulvar cancer

Cervical cancer, vaginal cancer, and vulvar cancer are related to HPV infection. Women who have had cervical, vaginal, or vulvar cancer have a higher risk of anal cancer.

HIV infection/AIDS

Being infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is a strong risk factor for anal cancer. HIV is the cause of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). HIV weakens the body’s immune system and its ability to fight infection. HPV infection of the anus is common among patients who are HIV-positive.

The risk of anal cancer is higher in men who are HIV-positive and have sex with men compared with men who are HIV-negative and have sex with men. Women who are HIV-positive also have an increased risk of anal cancer compared with women who are HIV-negative.

Studies show that intravenous drug use or cigarette smoking may further increase the risk of anal cancer in patients who are HIV-positive.

Immunosuppression

Immunosuppression is a condition that weakens the body’s immune system and its ability to fight infections and other diseases. Chronic (long-term) immunosuppression may increase the risk of anal cancer because it lowers the body’s ability to fight HPV infection.

Patients who have an organ transplant and receive immunosuppressive medicine to prevent organ rejection have an increased risk of anal cancer.

Having an autoimmune disorder such as Crohn disease or psoriasis may increase the risk of anal cancer. It is not clear if the increased risk is due to the autoimmune condition, the treatment for the condition, or a combination of both.

Certain sexual practices

The following sexual practices increase the risk of anal cancer because they increase the chance of being infected with HPV:

-

Having receptive anal intercourse (anal sex).

-

Having many sexual partners.

-

Sex between men.

Men and women who have a history of anal warts or other sexually transmitted diseases also have an increased risk of anal cancer.

Cigarette smoking

Studies show that cigarette smoking increases the risk of anal cancer. Studies also show that current smokers have a higher risk of anal cancer than smokers who have quit or people who have never smoked.

The following protective factor decreases the risk of anal cancer:

HPV vaccine

The human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine is used to prevent anal cancer, cervical cancer, vulvar cancer, and vaginal cancer caused by HPV. It is also used to prevent lesions caused by HPV that may become cancer in the future.

Studies show that being vaccinated against HPV lowers the risk of anal cancer. The vaccine may work best when it is given before a person is exposed to HPV.

It is not clear if the following protective factor decreases the risk of anal cancer:

Condom use

It is not known if the use of condoms protects against anal HPV infection. This is because not enough studies have been done to prove this.

Cancer prevention clinical trials are used to study ways to prevent cancer.

Cancer prevention clinical trials are used to study ways to lower the risk of developing certain types of cancer. Some cancer prevention trials are conducted with healthy people who have not had cancer but who have an increased risk for cancer. Other prevention trials are conducted with people who have had cancer and are trying to prevent another cancer of the same type or to lower their chance of developing a new type of cancer. Other trials are done with healthy volunteers who are not known to have any risk factors for cancer.

The purpose of some cancer prevention clinical trials is to find out whether actions people take can prevent cancer. These may include eating fruits and vegetables, exercising, quitting smoking, or taking certain medicines, vitamins, minerals, or food supplements.

Coping with anal cancer

Many people feel worried, depressed, and stressed when dealing with cancer. Getting treatment for cancer can be hard on your mind and body. Keep talking with your healthcare team about any problems or concerns you may have. Work together to ease the effect of cancer and its symptoms on your daily life.

Here are tips:

- Talk with your family or friends.

- Ask your healthcare team or social worker for help.

- Speak with a counselor.

- Talk with a spiritual advisor, such as a minister or rabbi.

- Ask your healthcare team about medicines for depression or anxiety.

- Keep socially active.

- Join a cancer support group.

Cancer treatment is also hard on the body. To help yourself stay healthier, try to:

- Eat a healthy diet, with a focus on high-protein foods.

- Drink plenty of water, fruit juices, and other liquids.

- Keep physically active.

- Rest as much as needed.

- Talk with your healthcare team about ways to manage treatment side effects.

- Take your medicines as directed by your team.

When should I call my healthcare provider?

Your healthcare provider will talk with you about when to call. You may be told to call if you have any of the below:

- New symptoms or symptoms that get worse

- Signs of an infection, such as a fever

- Side effects of treatment that affect your daily function or don’t get better with treatment

Ask your healthcare provider what signs to watch for, and when to call. Know how to get help after office hours and on weekends and holidays.

Next steps

Tips to help you get the most from a visit to your healthcare provider:

- Know the reason for your visit and what you want to happen.

- Before your visit, write down questions you want answered.

- Bring someone with you to help you ask questions and remember what your provider tells you.

- At the visit, write down the name of a new diagnosis, and any new medicines, treatments, or tests. Also write down any new instructions your provider gives you.

- Know why a new medicine or treatment is prescribed, and how it will help you. Also know what the side effects are.

- Ask if your condition can be treated in other ways.

- Know why a test or procedure is recommended and what the results could mean.

- Know what to expect if you do not take the medicine or have the test or procedure.

- If you have a follow-up appointment, write down the date, time, and purpose for that visit.

- Know how you can contact your provider if you have questions.