Total Knee Replacement(TKR) is a viable treatment for symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee refractory to conservative measures. In those with end-stage degenerative changes compromising the articular cartilage affecting multiple compartments of the knee, the literature has yet to identify a potentially viable alternative option for the regeneration of cartilage. Thus, TKA has demonstrated reproducible, long-term, successful results in such patients concerning outcomes of decreased pain and improved overall quality of life.[rx]

Recent estimates project that by the year 2030 there will be 3.48 million TKAs performed annually.[rx] Although it is an extremely common and increasingly routine surgery, attention to detail is critical during the procedure to ensure that a well-balanced and functional TKA is performed to mitigate the risks of implanting components that might otherwise be subject to increased wear and early failure. Even with appropriate technique, new technologic advances, and a better understanding of knee kinematics, approximately 1 out of 5 people that undergo a TKA will remain unsatisfied.[rx][rx] There are numerous TKA designs and different levels of constraint that may be necessary for particular cases. Unicompartmental arthroplasty, cruciate-retaining, and posterior stabilizing implants are typically used as potential index procedure options. However, in patients with significant varus/valgus instability, those undergoing revision surgery including component revisions, patients with the pre-existing poor bone quality, or in the setting of appreciable osseous defects, more constrained prosthetic components are given consideration. These include, but are not limited to semi-constrained, hinged, or distal femoral replacement options.[rx]

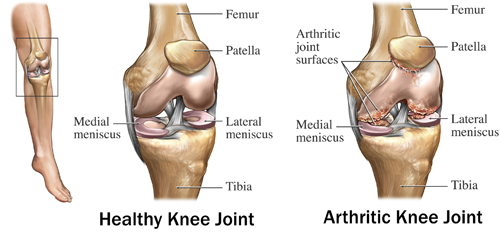

Anatomy and Physiology of Total Knee Replacement

The knee is made up of 3 separate compartments[rx]

-

Medial tibiofemoral joint

-

Lateral tibiofemoral joint

-

Patellofemoral joint

The knee is typically described as a hinged joint; however, there are more complex and subtle motion and dynamic considerations. Physiologically, the knee also undergoes axial rotation and femoral “rollback” in deeper degrees of flexion. Additionally, terminal rotatory motion, known as the “screw home mechanism,” occurs as the tibia externally rotates when the knee goes into terminal extension. The lateral tibial plateau is convex and sits more proximal than the medial tibial plateau which is concave. The medial femoral condyle is larger than the lateral side. 60% of the force through the knee joint occurs on the medial tibial plateau. Thus, the medial tibial plateau is of more dense bone, and this is also why the more common wear pattern seen in osteoarthritis occurs on the medial side.[rx]

Numerous ligaments act on the knee to provide stability of the joint including[rx][rx][rx]:

-

An anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) – Important for axial rotation as well as preventing anterior translation of the tibia on the femur

-

A posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) – Important for preventing posterior translation of the tibia on the femur, as well as allowing for femoral rollback.

-

Lateral collateral ligament (LCL) – Varus restraint, and is typically attenuated in significant varus deformity

-

Medial collateral ligament (MCL) – Valgus restraint, and is typically attenuated in significant valgus deformity

-

Posterolateral corner (PLC) – The primary stabilizer of external tibial rotation

Mechanical Alignment

- The distal femur is in approximately 9 degrees of anatomic valgus relative to the joint line while the proximal tibia in 3 degrees of anatomic varus relative to the joint line.

- The typical patellar Q angle is between 13 degrees and 19 degrees, with an increased Q angle increases the risk of patellar maltracking and dislocation. [rx]

Indications of Total Knee Replacement

The most common underlying diagnosis and indication for TKA are end-stage, degenerative osteoarthritis of the knee, with approximately 94- 97% of knee replacements performed for primary or post-traumatic osteoarthritis.[rx] These patients must have degenerative changes with pain and limitation of function in the knee that has failed conservative and non-operative measures. Other underlying diagnoses that may be treatable with a knee replacement include rheumatoid arthritis, peri-articular fractures, or malignancy. However, patients with malignancy may commonly require mega prostheses.[rx]

TKA is an elective procedure that is, in most cases, reserved for patients experiencing chronic, debilitating symptoms that continue to persist despite the exhaustion of all conservative and nonoperative treatment modalities.

Clinical symptoms of osteoarthritis include

-

Knee pain

-

Pain with activity and improving with rest

-

The pain gradually worsens over time

-

Decreased ambulatory capacity

Clinical evaluation includes

-

Full knee exam including a range of motion and ligamentous testing

Radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis include

Conservative treatment includes

-

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medication

-

Weight loss

-

Activity modification

-

Bracing

-

Physical therapy

-

Viscosupplementation

-

Intra-articular steroid injection

-

Decreased ambulatory capacity

Clinical evaluation includes

-

Full knee exam including a range of motion and ligamentous testing

Radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis include[rx]

-

Joint space narrowing

-

Subchondral sclerosis

-

Subchondral cysts

-

Osteophyte formation

Contraindications of Total Knee Replacement

There are few absolute contraindications for TKA including an active infection in the joint, and remote infection, or bacteremia. Relative contraindications include a significant vascular disease that may lead to poor wound healing and increased risk for infection. There is currently discussion and controversy in the literature as to risk stratification and increased complications associated with obesity. Patients with a BMI greater than 30 have an increased risk of infection and medical complications compared to non-obese patients. This risk further increases for those with a BMI greater than 40. Patients with BMI over 40 were found to have a statistically significant increase in superficial infection, deep infection, operative time, deep vein thrombosis (DVT), length of stay, renal insufficiency, reoperation, and wound dehiscence.[rx]

TKA is contraindicated in the following clinical scenarios

-

Local knee infection or sepsis

-

Remote (extra-articular), active, ongoing infection or bacteremia

-

Severe cases of vascular dysfunction

Absolute

-

Active or latent (less than 1 year) knee sepsis

-

Presence of active infection elsewhere in body

-

Extensor mechanism dysfunction

-

Medically unstable patient

Relative

-

Neuropathic joint

-

Poor overlying skin condition

-

Morbid obesity

-

Noncompliance due to major psychiatric disorder, alcohol, or drug abuse

-

Insufficient bone stock for reconstruction

-

Poor patient motivation or unrealistic expectation

-

Severe peripheral vascular disease

Equipment

Each implant company has a specific system with trays that come with the necessary tools and trial components. Basic equipment that will be used in all cases and will improve the efficiency and safety of the case include:

-

Standard operating table

-

De Mayo leg holder, paint roller, or other equivalent patient positioning instrumentation

-

Tourniquet

-

Overall use remains debated in the literature

-

Use and duration is surgeon-specific

-

-

Retractors

-

Osteotomes

-

Sagittal saw

-

Mallet

-

Lamina spreaders

-

Cement-specific equipment

-

Cement mixer system

-

Pressurizing gun

-

-

Pulse lavage irrigation

-

Suction

-

Bovie electrocautery

In revision cases, may also require other equipment including

-

Currettes

-

Reamers

-

Cones

-

Sleeves

-

Stemmed options including offset adjusting capabilities

-

Bone grafting options

Implant Types

Implant types have continued to evolve since the 1950s. Insall et al. initially described in the 1970s the different models of knee prostheses. He placed them into two categories; condylar replacements that spared ligaments, and hinged-type components that sacrificed the ligaments. Four models were described, with increasing complexity in each model[13]:

-

Unicondylar

-

Duocondylar

-

Geometric

-

Guepar

In modern arthroplasty, most implants are a derivative of these models that were initially described. From least complex to most complex they include unicompartmental, cruciate retaining, posterior stabilizing, constrained non-hinged, constrained hinged prosthetic components.[rx][rx][rx]

Cruciate Retaining (CR)

The ACL is sacrificed, overall feasibility mandates a competent and functional PCL.

Can be used in those with mild varus/valgus deformity. Should be avoided in those with inflammatory arthritis due to increased risk for short-term or delayed rupture of PCL.

Benefits

-

fewer patellar complications (theoretical)

-

Increased quadriceps strength (controversial, depends in part on surgical exposure utilized)

-

Improved stair climbing

-

Preserved PCL proprioception (theoretical)

-

Lower shear forces on the tibial component

-

Improved femoral bone stock preservation

-

Preserves near-normal knee kinematics

-

Avoids cam-post jump complication that exists in posterior stabilized prosthetic components

Disadvantages

-

Risk of postoperative PCL degeneration or rupture that can lead to flexion instability

-

Tight PCL can lead to increased wear on polyethylene and dysfunctional TKA kinematics

Posterior Stabilizing (PS)

Can be used in those with absent PCL, inflammatory arthritis, and may be beneficial in those with a previous patellectomy as it can add some anteroposterior stability that is absent due to the weak extensor mechanism. PS femoral prosthetic component contains a box in the femoral component with a post on the polyethylene liner that substitutes for the resected PCL.

Benefits

-

Can theoretically be easier to achieve ligamentous balance in the knee without having to worry about accounting for the physiologic effects of the intact PCL

-

Greater deformity correction compared to cruciate-retaining implants

-

Theoretically improved knee range of motion

-

Decreased polyethylene wear due to congruent articular surfaces

Disadvantages

-

Cam-post jump of the post over the femoral box, typically due to mid-late flexion instability

-

Polyethylene wear on post can lead to osteolysis

-

Patellar clunk that may occur due to a soft tissue nodule and is present when going from flexion into extension

-

The increased theoretical risk of technical error which can involve elevating the joint line

Overall, multiple studies have not demonstrated a significant difference in function, satisfaction or implant survival between cruciate-retaining and posterior stabilizing implants.

Constrained Non-Hinged

Varus-valgus constrained design is used in cases where there is LCL or MCL deficiency, moderate bone loss, or flexion gap laxity. This implant has a large tibial post with a deep femoral box.

Benefits

-

Allows for coronal stability in severe coronal bone deformities

Disadvantages

-

Increased femoral bone loss and is a poor option in younger patients unless necessary.

-

Increased risk of aseptic loosening due to increased constraint

-

Increased polyethylene wear and increased risk of cam fracture

Constrained Hinge

Rotating hinge prostheses are used in complex revision arthroplasty cases with significant bone loss, ligamentous laxity, or in oncologic cases. Femoral and tibial components link with an axle and the tibial bearing can rotate around the tibial platform. This rotation allows for a lower constraint and therefore a decreased risk of aseptic loosening. Early implants were uniplanar without allowing rotation and had a high rate of aseptic loosening.

Advantages

-

Very versatile and has application for many salvage cases

Disadvantages

-

Significant bone resection needed for implant

-

Although lower with a rotating hinge, still at risk for aseptic loosening due to increased constraint

Personnel

Total joint arthroplasty has transitioned from a fee for service to a bundled payment to incentivize quality of care over the quantity of cases. In 2015, the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced the Comprehensive Care for Joint Replacement Model (CJR). Bozic et al. in 2014 demonstrated that 70% of the total cost was post-discharge and they have created CJR in hopes of stimulating a reduction in cost and complications. This effort has led to the development of standardized protocols and an interprofessional approach for patients undergoing knee replacement. At our institution, personnel integral to the success of a knee replacement include[rx]:

-

Primary care physician

-

Joint class instructor

-

Pre-operative intra-operative and post-anesthesia nurses

-

Scrub technician, circulating RN

-

Implant representative

-

Physician assistant/first assistant

-

Resident physician

-

Orthopedic surgeon

-

Case manager

-

Inpatient occupational and physical therapist

-

Outpatient physical therapist

-

Home health nurse

Preparation

Non-Operative Management

Numerous non-operative treatments are employed in the pre-surgical management of knee arthroplasty. Treatments include both pharmacologic and non-pharmacologic options. Multiple studies have investigated these different treatment options, and guidelines have been put in place by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons in the 2013 evidence-based guidelines, 2nd edition.[rx]

The AAOS recommends with strong evidence for low-impact aerobic exercises, neuromuscular education, and strengthening. They also recommend strongly for the use of NSAIDs and tramadol.[rx]

The AAOS recommends moderate weight loss in patients with a BMI greater than 25.

The AAOS recommends strongly against acupuncture, glucosamine/chondroitin, viscosupplementation.

The AAOS recommends moderate against lateral wedge insoles.

The AAOS cannot recommend for or against manual therapy (i.e., chiropractic, joint manipulation), physical agents including electrotherapeutic modalities, biologic injections, corticosteroid injections, valgus directing force brace, acetaminophen, opioids, or pain patches.

Pre-operative Evaluation

A review of the literature did not demonstrate a uniform protocol as to what pre-operative evaluation is necessary before knee replacement. A thorough history and physical exam are necessary. Co-morbidities, smoking status, alcohol consumption, and mental status should all undergo evaluation. The patient risk for the development of thromboembolic events should be a consideration. However, typically, most patients will undergo an evaluation and pre-operative clearance by their primary care provider and potentially cardiologist if significant cardiac co-morbidities are present. Other subspecialty pre-operative evaluations may be necessary depending on patients’ other co-morbidities (i.e., rheumatology, nephrology, neurology). Bernstein et al. developed a protocol that assessed patients for 19 different risk factors. Identifying these risk factors allowed for pre-operative intervention and these patients were found to have a statistically significant shorter length of stay, and lower average total direct variable cost. No difference was noted in the patients’ 90-day readmission rate.[rx][rx]

Pre-operative Surgical Planning

It is essential to assess for previous surgical incisions, patients limb-lengths, limb deformity, the range of motion, ligamentous stability and gait. Patients neurovascular status should also be considered, Ankle-brachial index may be a prudent screening, and if less than 0.9, avascular consultation should be obtained. Patients with pre-existing peripheral vascular disease should also have their PAD assessed.

Plain radiography typically provides sufficient detail, and further studies are typically not necessary. Weight-bearing AP, lateral and sunrise views should be routinely performed. AP hip to ankle x-rays allow for the evaluation of extra-articular deformities and allow for assessment of the mechanical axis. Radiographic markers can be placed during imaging to allow for the use of templating software to assess for estimated implant sizing and positioning. A lateral patellar shift of more than 3mm was an independent risk factor for patellar maltracking. Images should be interpreted to assess for the Insall-Salvati ratio, a pre-existing slope of the tibial plateau, and coronal alignment. Custom implants are made based on CT or MRI sequences, and these studies should be performed when a custom implant is desired. Custom implants can be particularly helpful in patients with significant deformity where intramedullary or extra-medullary guides will not work, as well as in patients with pre-existing hardware.

Laboratory testing

Basic pre-operative labs should be performed such as CBC, BMP, HbA1c in diabetic patients. A goal of HbA1c of less than 7.0 is desirable; however, studies have shown that an HbA1c under 8.0 is acceptable to avoid excessive delay and complications in knee replacement. Many centers also perform a pre-operative urinalysis and nasal swabs/decolonization in potential MRSA carriers.[rx] Other considerations include checking a total lymphocyte count (TLC) and serum albumin as these are markers of potential underlying malnutrition that may increase the risk of wound complications following the elective TKA procedure.[rx]

Technique

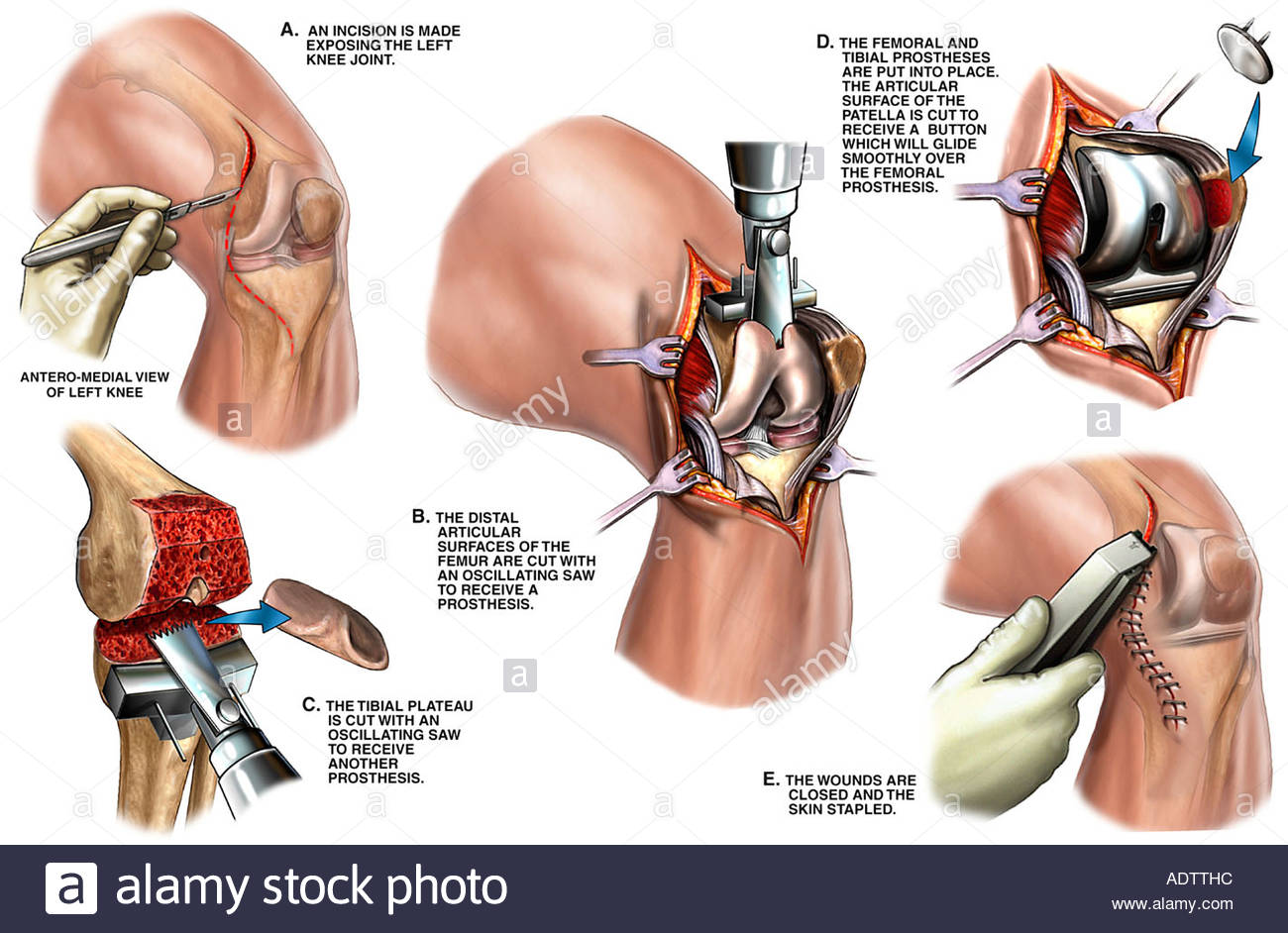

Surgical Technique

Patients are typically placed supine on the operative table; a general or spinal anesthetic is administered. A systematic review performed by Johnson et al. found no statistically significant differences between the two including mortality, surgical duration, or nerve palsy.[rx] Typically a standard midline incision with a medial parapatellar arthrotomy is used. However, other approaches include the lateral parapatellar approach, midvastus, and subcastes approach. More extensile approaches include the quadriceps snip, V-Y turndown, and tibial tubercle osteotomy.[rx] It is essential during the approach to maintain thick skin flaps and to respect the blood flow that comes from medial to lateral. Maintaining a small cuff is necessary during the arthrotomy to allow for adequate repair at the conclusion of the procedure. The medial soft tissues at the proximal tibia are skeletonized off of the bone, and a soft tissue release is performed medially. [rx]The same procedure is performed on the lateral side. However, most cases involve varus deformities, and a more extensive medial release is the choice. The infrapatellar fat pad can either be partially or completely excised. The medial and lateral meniscus, as well as ACL, will require excision. The PCL should also be sacrificed if a posterior stabilizing implant is desired. It is not necessary to resurface the patella in all cases. However, in patients with significant anterior knee pain or patellofemoral arthritis, it should be. It is worth noting that the revision rate and incidence of anterior knee pain are higher in those that do not undergo resurfacing. But those with resurfacing have a higher chance of complications such as tendon injury or fracture. Overall the patient satisfaction rates are equal between the two treatments.[rx]

The sequence of steps during knee arthroplasty will be dependent on the technique selected by the operative surgeon. These techniques include:

Measured Resection

-

Traditionally was associated with cruciate-retaining implants, however, can also be used for PS implants as well.

-

Most surgeons desire a neutral mechanical axis, and the femur is cut in 5 to 7 degrees of valgus with approximately 9 to 10mm of bony resection distally. The tibia is cut perpendicularly to the tibial axis. Typically an intramedullary guide is utilized on the femur, and an extramedullary guide is utilized on the tibia. The anatomic slope of the tibial plateau is restored if CR implant is to be used. Should be a neutral tibial plateau cut if PS implant is being used due to risk for CAM jump phenomenon with an increased tibial slope.

-

Anatomic landmarks are used to reference a neutral femoral implant rotation.

-

Transepicondylar axis(TEA): Connects lateral condyle prominence to sulcus of the medial epicondyle. Implants placed parallel to this will provide a rectangular flexion gap and result in improved patellofemoral tracking, femorotibial kinematics, and coronal stability.

-

Whiteside line(AP axis of femur): Starts at the center of the trochlear sulcus and ends posteriorly at the midpoint of intercondylar notch and typically is perpendicular to TEA.

-

Posterior Condylar axis (PCA): Goes based upon a line connecting posterior condyles, in most cases externally rotating the posterior condylar axis by 3 degrees will create a line parallel to the TEA. This, however, can be very deceiving in patients with a valgus knee and hypoplastic lateral femoral condyle and can lead to malrotation of the implant.

-

-

Osteophytes should be removed before any bone cuts.

-

The pitfall of the technique is that it is difficult to perform soft-tissue releases after performing bony cuts. Ligament releases after bony cuts can affect the flexion/extension gaps and lead to poor balancing. Changing ligament tension in extension will affect the flexion gap and vice versa.

-

There is an increased incidence of femoral condylar liftoff in this technique compared to gap balancing

Gap Balancing

-

Traditionally associated with PS implants, but can be used for CR as well.

-

Before any bony cuts or soft tissue release, the removal of all osteophytes is necessary; this is particularly important in gap balancing because removing osteophytes after balancing will change the ligamentous tension and will affect flexion/extension gaps.

-

Typically a proximal tibial cut is performed then lamina spreaders are placed on medial and lateral sides to assess tension on both sides in extension. Structures are released until a neutral alignment, and symmetric extension gap is achieved.

-

The same steps are then performed with the knee at 90 degrees of flexion. A rectangular flexion gap equal to the extension gap is desired, the posterior femoral condyle cuts are then performed.

-

Joint line elevation is a potential pitfall of this technique and can lead to abnormal contact forces on the patellofemoral joint as well as mid-flexion instability.

Hybrid Technique

-

The hybrid technique is a blend of the two techniques described above.

Patellar maltracking is one of the most common complications encountered in knee arthroplasty. Iatrogenic causes of the complication can be avoided by:

-

Lateralizing femoral and tibial implants

-

Avoiding internal rotation of the femoral and tibial prosthesis

-

Avoiding overstuffing or under-sizing patellar component

-

Medializing patellar component

A uniform strategy for wound closure does not exist, and many studies have found different materials to be superior. Typically a heavy ethibond suture or barbed suture is used for arthrotomy closure. Followed by absorbable suture or barbed suture is used for the deep and superficial dermis. Skin closure can be with either a running non-braided absorbable suture with either derma bond/steri-strips or staples. Silver lined dressings can be used and should be maintained for several days without being removed until drainage has stopped. For complex revisions or in high-risk patients, incisional wound vacs or negative pressure dressings are also an option.[rx]

Complications

-

Periprosthetic Fracture

Periprosthetic fractures can occur in the distal femur, proximal tibia, or patella. They are most commonly located in the supracondylar region of the distal femur. The most common classification system used for periprosthetic fractures of the distal femur is the Lewis and Rorabeck classification. In this classification system, type-I is non-displaced with a stable component; type-II has more than 5mm of displacement or greater than 5 degrees of angulation with a stable component, and type-III has a loose component. There are several additional classification systems; All of which fail to classify intra-operative periprosthetic fractures. The anatomic location is typically used to describe these fractures. Risk factors that may predispose patients to periprosthetic fractures include:

-

Anterior notching of the femur

-

Osteoporosis, osteolysis

-

Implant loosening

-

Rheumatoid arthritis

-

Neurologic disorder

-

Corticosteroid use

-

Increased age

-

Female sex

Treatment options can include open reduction internal fixation, knee immobilizer, revision arthroplasty if components are loose, or distal femoral replacement, if there is not adequate bone stock or significant comminution, is present.[rx][rx][rx]

Prosthetic Joint infection

-

Occurs in 1 to 2% of primary knee replacements

-

Most common pathogens:

-

Staphylococcus aureus

-

Staphylococcus epidermidis

-

-

Acute infection

-

Within 6 weeks of surgery

-

-

Chronic infection

-

After 6 weeks of surgery

-

-

Laboratory evaluation

-

CBC

-

ESR

-

CRP

-

IL-6

-

Synovial analysis

-

WBC count

-

27800 is the cutoff in the first 6 weeks after surgery

-

Following 6 weeks, WBC count of 1100 is suggestive of infection

-

-

Culture

-

Gram stain

-

Alpha-defensin

-

-

-

Treatment:

-

IV antibiotics for 12 weeks

-

In acute infections, a polyethylene liner exchange in addition to synovectomy and irrigation and debridement can be attempted.

-

50 to 55% success rate

-

-

In chronic infections or those that have failed other treatments a two-stage revision is recommended and is the gold standard in the United States. In Europe, a one stage revision is routinely performed.

-

Two-stage revision involves the placement of an antibiotic spacer for approximately 2 to 3 months.

-

These spacers typically have 3 grams of vancomycin and 4 grams of tobramycin per 40-gram bag of cement used.

-

Spacers can be either static or articulating.

-

With two stage revision, repeat frozen section should be performed before reimplantation.

-

Persistence of infection is demonstrated by greater than 5 PMN per hpf in 5 hpf at x400 magnification

-

-

-