Shock results from four potential, and not necessarily exclusive, pathophysiological mechanisms[rx] hypovolemia (from internal or external fluid loss), cardiogenic factors (e.g., acute myocardial infarction, end-stage cardiomyopathy, advanced valvular heart disease, myocarditis, or cardiac arrhythmias), obstruction (e.g., pulmonary embolism, cardiac tamponade, or tension pneumothorax), or distributive factors (e.g., severe sepsis or anaphylaxis from the release of inflammatory mediators) and the interactive graphic, available at NEJM.org). The first three mechanisms are characterized by low cardiac output and, hence, inadequate oxygen transport. In distributive shock, the main deficit lies in the periphery, with decreased systemic vascular resistance and altered oxygen extraction. Typically, in such cases, cardiac output is high, although it may be low as a result of associated myocardial depression. Patients with acute circulatory failure often have a combination of these mechanisms. For example, a patient with distributive shock from severe pancreatitis, anaphylaxis, or sepsis may also have hypovolemia and cardiogenic shock from myocardial depression.

What are Circulatory Pathways/The circulatory system includes the lymphatic system, which circulates lymph. The passage of lymph takes much longer than that of blood. Blood is a fluid consisting of plasma, red blood cells, white blood cells, and platelets that is circulated by the heart through the vertebrate vascular system, carrying oxygen and nutrients to and waste materials away from all body tissues. Lymph is essentially recycled excess blood plasma after it has been filtered from the interstitial fluid (between cells) and returned to the lymphatic system. The cardiovascular (from Latin words meaning “heart” and “vessel”) system comprises the blood, heart, and blood vessels.[rx] The lymph, lymph nodes, and lymph vessels form the lymphatic system, which returns filtered blood plasma from the interstitial fluid (between cells) as lymph.

What are Circulatory Pathways/Circulatory Routes?

Every other cell, tissue, and organ in the body is impacted to a great extent by the circulatory system of the body. This system is the most complex system, with the three main components of blood, blood vessels, and heart. The blood travels through the entire body through the arteries and veins. This is how circulation occurs in the body.

The pattern through which circulation happens is called the Circulatory pathway. This pathway can be classified into two types – The open system of circulation and the closed system of circulation.

The open system of circulation is clearly visible in the two phyla Arthropoda and Mollusca. Here the blood that is pumped by the heart goes through large vessels into the open body cavities. But, when you see two other prominent phyla, Phylum Annelida and Phylum Chordata, you can see that there is a closed circulatory system. Blood is always circulated through closed blood vessels here. This closed pathway is said to be more advantageous, as the blood flow can be regulated with precision.

The Aorta and Its Branches for Circulatory Routes

The aorta is the largest artery in the body and is divided into 3 parts: the ascending aorta, arch of the aorta, and descending aorta.

Key Points

The blood is pumped from the left ventricle into the aorta and from there branches to all parts of the body.

The aorta is divided into three parts: the ascending aorta (where the aorta initially leaves the heart and points toward the head), the arch of the aorta (where the aorta changes direction), and the descending aorta (where the aorta points toward the feet).

The ascending aorta has two small branches, the left and right coronary arteries, that provide blood to the heart muscle.

The arch of the aorta has three branches: the brachiocephalic artery (which divides into right common carotid artery and the right subclavian artery), the left common carotid artery, and the left subclavian artery. These arteries provide blood to both arms and the head.

Within the abdomen, the descending aorta branches into the two common iliac arteries; these provide blood to the pelvis and, eventually, the legs.

Key Terms

- descending aorta: The region of the aorta that passes inferiorly towards the feet.

- ascending aorta: The region of the aorta directly attached to the heart that passes superiorly towards the head.

- arch of the aorta: The region of the aorta that changes direction between the ascending and descending aorta.

The aorta is the largest artery in the systemic circulatory system. Blood is pumped from the left ventricle into the aorta and from there branches to all parts of the body. The aorta is an elastic artery, meaning it is able to distend. When the left ventricle contracts to force blood into the aorta, the aorta expands. This stretching generates the potential energy that helps maintain blood pressure during diastole, since during this time the aorta contracts passively.

Diagram of Human Heart: This diagram of the human heart shows all the major vessels, and arrows indicate the direction of flow through the heart.

The aorta is divided into three parts: the ascending aorta, where the aorta initially leaves the heart and points superiorly toward the head; the arch of the aorta where the aorta changes direction; and the descending aorta where the aorta points inferiorly toward the feet.

Ascending Aorta: The aorta has three parts: the ascending, the arch and the descending.

The ascending aorta has two small branches, the left and right coronary arteries. These arteries provide blood to the heart muscle, and their blockage is the cause myocardial infarctions or heart attacks.

The arch of the aorta has three branches: the brachiocephalic artery, which itself divides into right common carotid artery and the right subclavian artery, the left common carotid artery, and the left subclavian artery. These arteries provide blood to both arms and the head.

The descending aorta is the largest artery in the body; it runs from the heart down the length of the chest and abdomen. It is divided into two portions, the thoracic and abdominal, in correspondence with the two great cavities of the trunk in which it sits. Within the abdomen, the descending aorta branches into the two common iliac arteries that provide blood to the pelvis and, eventually, the legs.

Ascending Aorta

The ascending aorta is the first portion of the aorta; it includes the aortic sinuses, the bulb of the aorta, and the sinotubular junction.

Key Points

The ascending aorta passes diagonally upward, forward, and to the right, in the direction of the heart ‘s axis.

The aortic sinuses end at the sinotubular junction, the point in the ascending aorta where the aorta becomes a tubular structure.

The ascending aorta has two branching vessels, the left and right coronary arteries, which supply blood to the heart muscle.

Key Terms

- aortic sinuses: An aortic sinus is one of the anatomic dilations of the ascending aorta, which occurs just above the aortic valve.

- sinotubular junction: The sinotubular junction is the point in the ascending aorta where the aortic sinuses end and the aorta becomes a tubular structure.

- bulb of the aorta: At the union of the ascending aorta with the aortic arch, the caliber of the vessel increases with a bulging of its right wall. This dilation is termed the bulb of the aorta, and on transverse section presents a somewhat oval figure.

The ascending aorta is a portion of the aorta beginning at the upper part of the base of the left ventricle, on a level with the lower border of the third costal cartilage behind the left half of the sternum; it passes diagonally upward, forward, and to the right, in the direction of the heart’s axis, as high as the upper border of the second right costal cartilage. Its total length is about five centimeters.

Ascending Aorta: The aorta has three parts: the ascending, the arch and the descending.

The aortic root is the portion of the ascending aorta beginning at the aortic annulus, the fibrous attachment between the heart and the aorta, and extending to the sinotubular junction. Just above the aortic valve are three small dilations called the aortic sinuses. The two anterior sinuses give rise to the coronary arteries, while the third posterior sinus does not usually give rise to any vessels and so is known as the non-coronary sinus.

The sinotubular junction is the point in the ascending aorta where the aortic sinuses end and the aorta becomes a tubular structure.

At the junction of the ascending aorta with the aortic arch, the caliber of the vessel increases with a bulging of its right wall. This dilatation is termed the “bulb of the aorta.” The ascending aorta is contained within the pericardium. It is enclosed in a tube of the serous pericardium, which also encloses the pulmonary artery.

The ascending aorta is covered at its beginning by the trunk of the pulmonary artery and, higher up, is separated from the sternum by the pericardium, the right pleura, the anterior margin of the right lung, some loose areolar tissue, and the remains of the thymus. Posteriorly, it rests upon the left atrium and right pulmonary artery.

Arch of the Aorta

The arch of the aorta follows the ascending aorta and begins at the level of the second sternocostal articulation of the right side.

Key Points

Three vessels come out of the aortic arch: the brachiocephalic artery, the left common carotid artery, and the left subclavian artery.

These vessels supply blood to the head, neck, thorax and upper limbs.

In some individuals, the left common carotid artery and left subclavian artery may arise from the brachiocephalic artery rather than the aortic arch.

Key Terms

- arch of the aorta: Also called the transverse aortic arch, is continuous with the upper border of the ascending aorta and begins at the level of the upper border of the second sternocostal articulation of the right side.

Aortic arch: This diagram shows the arch of the aorta and its branches.

The arch of the aorta, or the transverse aortic arch, is continuous with the upper border of the ascending aorta and begins at the level of the upper border of the second sternocostal articulation of the right side. The arch of the aorta runs at first upward, backward, and to the left in front of the trachea; it is then directed backward on the left side of the trachea and finally passes downward on the left side of the body of the fourth thoracic vertebra. At the lower border, this vertebra becomes continuous with the descending aorta.

Three vessels come out of the aortic arch: the brachiocephalic artery, the left common carotid artery, and the left subclavian artery. These vessels supply blood to the head, neck, thorax and upper limbs. In approximately 20% of individuals, the left common carotid artery arises from the brachiocephalic artery rather than the aortic arch, and in approximately 7% of individuals the left subclavian artery also arises here.

Thoracic Aorta

The thoracic aorta is the section of the aorta that travels through the thoracic cavity to carry blood to the head, neck, thorax and arms.

Key Points

The thoracic aorta is contained in the posterior mediastinal cavity, begins at the 4th thoracic vertebra where it is continuous with the aortic arch, and ends in front of the lower border of the twelfth thoracic vertebra.

Branches from the thoracic aorta include the bronchial arteries, the mediastinal arteries, the esophageal arteries, the pericardial arteries, and the superior phrenic artery.

The thoracic aorta and the esophagus run parallel for most of its length, with the esophagus lying on the right side of the aorta. At the lower part of the thorax, the esophagus is placed in front of the aorta, situated on its left side close to the diaphragm.

Key Terms

- mediastinal cavity: The central compartment of the thoracic cavity. It contains the heart, the great vessels of the heart, the esophagus, the trachea, the phrenic nerve, the cardiac nerve, the thoracic duct, the thymus, and the lymph nodes of the central chest.

- Thoracic Aorta: Contained in the posterior mediastinal cavity, it begins at the lower border of the fourth thoracic vertebra where it is continuous with the aortic arch, and ends in front of the lower border of the twelfth thoracic vertebra, at the aortic hiatus in the diaphragm where it becomes the abdominal aorta.

Thoracic aorta: The aorta, highlighted in red, includes the thoracic aorta, the section of the aorta which runs from the lower border of the fourth thoracic vertebra to the diaphragm.

The thoracic aorta forms part of the descending aorta and is continuous with the aortic arch at its origin before becoming the abdominal aorta. Contained within the posterior mediastinal cavity, it begins at the lower border of the fourth thoracic vertebra where it is continuous with the aortic arch, and ends in front of the lower border of the twelfth thoracic vertebra at the aortic hiatus in the diaphragm. At its commencement, the thoracic aorta is situated on the left of the vertebral column; it approaches the median line as it descends, and at its termination lies directly in front of the column.

The thoracic aorta’s relation, from above downward, is as follows: anteriorly with the root of the left lung, the pericardium, the esophagus and the diaphragm; posteriorly with the vertebral column; on the right side with the hemiazygos veins and thoracic duct; and on the left side with the left pleura and lung. The esophagus lies on the right side of the aorta for most of its length, but at the lower part of the thorax is placed in front of the aorta and close to the diaphragm, situated on its left side.

As it descends in the thorax, the aorta gives off several paired branches. In descending order these are the bronchial arteries, the mediastinal arteries, the esophageal arteries, the pericardial arteries, and the superior phrenic artery. The posterior intercostal arteries are branches that originate throughout the length of the posterior aspect of the thoracic aorta.

Abdominal Aorta

The abdominal aorta is the largest artery in the abdominal cavity and supplies blood to most of the abdominal organs.

Key Points

The abdominal aorta lies slightly to the left of the midline of the body.

The abdominal aorta has a venous counterpart called the inferior vena cava that travels parallel to it on its right side.

The abdominal aorta branches into many arteries that supply blood to the abdominal organs.

Key Terms

- abdominal aorta: The largest artery in the abdominal cavity. As part of the aorta, it is a direct continuation of the descending aorta (of the thorax).

- omentum: Either of two folds of the peritoneum that support the viscera.

- inferior vena cava: The large vein which returns blood from the lower extremities and the pelvic and abdominal organs to the right atrium of the heart.

Abdominal Aorta: The aorta, highlighted in red, includes the abdominal aorta which begins at the diaphragm and ends as it branches into the common iliac arteries.

The abdominal aorta is the largest artery in the abdominal cavity. As part of the descending aorta, it is a direct continuation of the thoracic aorta.

It begins at the level of the diaphragm, crossing it via the aortic hiatus. This hole in the diaphragm that allows the passage of the great vessels at the vertebral level of T12. The abdominal aorta travels down the posterior wall of the abdomen, anterior to the vertebral column, following the curvature of the lumbar vertebrae. The abdominal aorta runs parallel to the inferior vena cava, located just to the right of the abdominal aorta.

The abdominal aorta lies slightly to the left of the midline of the body. It is covered anteriorly by the lesser omentum and stomach. Posteriorly, it is separated from the lumbar vertebrae by the anterior longitudinal ligament and left lumbar veins.

The abdominal aorta supplies blood to much of the abdominal cavity through numerous branches that become smaller in diameter as it descends. Terminally it branches into the paired common iliac arteries, which supply the pelvis and lower limbs.

Arteries of the Pelvis and Lower Limbs

The abdominal aorta divides into the major arteries of the leg: the femoral, popliteal, tibial, dorsal foot, plantar, and fibular arteries.

Key Points

The pelvic cavity is supplied by the paired internal iliac arteries.

The internal iliac artery divides into posterior and anterior trunks which supply the reproductive and other organs of the pelvis with blood.

Key Terms

- internal iliac arteries: Formed when the common iliac artery divides the internal iliac artery at the vertebral level L5 descends inferiorly into the lesser pelvis.

Internal Iliac Artery: The division of the internal iliac artery into its posterior and anterior trunks.

The pelvic cavity is largely supplied by the paired internal iliac arteries, formed when the common iliac artery divides the internal iliac artery at the vertebral level L5 descends inferiorly into the lesser pelvis. The external iliac artery passes into the thigh, becoming the femoral artery.

At the most superior border of the greater sciatic foramen, the large opening to the rear of the pelvis, the internal iliac artery divides into anterior and posterior trunks.

The anterior trunk gives rise to numerous arteries that supply the organs of the pelvis and the gluteal and adductor muscles of the leg. Key branches include the obturator artery, the inferior vesical artery in men and the equivalent vaginal artery in females, and the rectal and gluteal arteries.

The posterior trunk gives rise to arteries that supply the posterior pelvic wall and the gluteal region, including the iliolumbar artery that supplies the psoas major muscle, the lateral sacral arteries, and the superior gluteal artery.

Principal Veins

Veins are blood vessels that carry blood towards the heart, have thin, inelastic walls, and contain numerous valves.

Key Points

Veins, blood vessels that return blood to the heart, are different in structure and function from the arteries, which carry blood to the circulation.

Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart. The exceptions are the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenated blood to the heart, but the umbilical vein deteriorates shortly after birth.

The venae cavae are two large veins that drain into the right atrium of the heart, returning the majority of blood from the systemic circulation.

Key Terms

- vein: A blood vessel that transports blood from the capillaries back to the heart.

In the circulatory system, veins are blood vessels that carry blood towards the heart. Veins have thin, inelastic walls, and contain numerous valves in order to prevent the backflow of blood. Most veins carry deoxygenated blood from the tissues back to the heart with the exceptions of the pulmonary and umbilical veins, both of which carry oxygenated blood to the heart.

Principle Veins: This diagram shows the principal veins of the human body and their locations.

Veins can be broadly classified based on their depth within the body. Superficial veins are located close to the surface of the body and have no corresponding arteries, such as the great saphenous vein which runs the length of the leg. The deep veins lie deeper in the body and often run adjacent to corresponding arteries, such as the femoral vein which sits adjacent to the femoral artery in the thigh. Deep veins are often of larger caliber than superficial veins and carry the majority of the blood within the circulatory system. Communicating veins, or perforator veins if they pass through a large muscle mass, directly connect superficial and direct veins. The above veins form part of the systemic circulatory system. The pulmonary veins and venules that run from the lungs to the heart form part of the pulmonary circulatory system and are distinct from other veins in that they carry oxygenated blood.

Venae Cavae

The venae cavae are the veins with the largest diameter. Both enter the right atrium of the heart with the superior vena cava carrying blood from the arms, head, and thoracic cavity and the inferior vena cava carrying blood from the legs and abdomen. The inferior vena cava runs parallel to the abdominal aorta.

The superior vena cava is formed from the brachiocephalic veins which are in turn formed from the subclavian and internal jugular veins that serve the arm and head respectively. The inferior vena cava is formed from the common iliac veins that serve the legs and abdomen. The renal and hepatic veins from the kidneys and liver respectively also feed into the inferior vena cava.

Other Important Veins

Other important venous systems include the cardiac veins, which return blood from the heart tissue back to the general circulation. The cardiac veins merge into the coronary sinus, which empties directly into the right atrium.

The pulmonary veins are large blood vessels which receive oxygenated blood from the lungs and return it to the left atrium of the heart. There are four pulmonary veins, two from each lung, each of which forms from three to four bronchial veins. In approximately 25% of individuals, the left pulmonary veins may merge into a single vein; the same effect on the right side is only seen in approximately 3% of individuals.

The hepatic portal vein carries blood from the gastrointestinal tract to the liver. The portal vein is often described as a false vein because it conducts blood between capillary networks rather than between a capillary network and the heart. It functions to supply the liver with blood and required metabolites, but also ensures that ingested substances are first processed in the liver before reaching the wider systemic circulation.

Veins of the Head and Neck

In the head and neck, blood circulates from the upper systemic loop, which originates at the aortic arch.

Key Points

The dural sinuses within the dura mater surrounding the brain receive blood from the brain. From these sinuses, blood eventually enters the internal jugular vein.

The head and neck are emptied of blood by the internal and external jugular veins.

Key Terms

- jugular vein: Any of several veins on each side of the neck that drain the brain, face and neck of deoxygenated blood.

Two main jugular veins are responsible for the venous draining of the head and neck.

Veins of the Head and Neck: The veins of head and neck are labeled in blue, with an arrow pointing to the auricular vein.

The superficial external jugular vein is formed from the retromandibular vein and the posterior auricular vein at a point adjacent to the mandible. The external jugular vein passes down the neck and underneath the clavicle before draining into the subclavian vein.

The deep-lying internal jugular vein receives blood from the dural venous sinuses in the brain as well as the cerebral and cerebellar veins. Dural sinuses are composed of dural mater lined with endothelium, making them distinct from arteries, veins, and capillaries. The dural sinuses receive blood from the veins that drain the brain and skull.

Formed at the base of the brain from the inferior petrosal sinus and the sigmoid sinus, the internal jugular vein runs down the side of the neck adjacent to the internal carotid artery. As well as removing blood from the brain, the anterior retromandibular, facial, and lingual veins also drain into the internal jugular. Upon exiting the neck, the internal jugular vein merges with the subclavian vein to form the brachiocephalic vein.

Additional veins such as the occipital, deep cervical, and thyroid veins drain directly into the brachiocephalic vein.

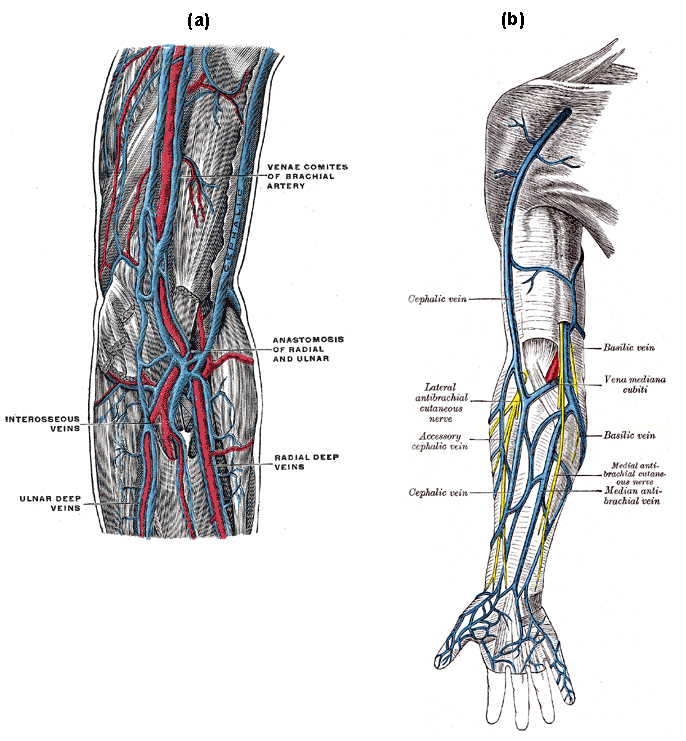

Veins of the Upper Limbs

The veins of the upper extremity are divided into superficial and deep veins, indicating their relative depths from the skin.

Key Points

The brachial, radial, and ulnar veins are the major deep veins that drain blood from the arm.

The major superficial veins of the arm include the cephalic and basilic veins, as well as the median cubital vein which joins the two at the elbow.

At the shoulder, the brachial and basilic veins merge to form the axillary vein, to which the cephaliac vein merges to form the subclavian vein.

Key Terms

- brachial vein: Runs from the elbow to the shoulder parallel to the brachial artery.

- cephalic vein: Arises from the dorsal venous network of the hand and passes the elbow anteriorly, continuing up the upper arm to the shoulder.

- median cubital vein: The vein that links the basilic and cephalic veins.

- basilic vein: Located medially to the cephalic vein, following a similar path.

(a) Deep veins of the upper extremity (b) Superficial veins of the upper extremity: The veins of the upper extremity are divided into two sets, superficial and deep. The deep veins are shown in blue. The superficial veins of the upper extremity are shown in blue.

Veins of the arm are either deep or superficial and are responsible for draining the hand and arm.

The major deep veins of the arm are the radial and ulnar veins, which run along the length of their respective bones and merge at the elbow to form the paired brachial vein. The brachial vein runs from the elbow up to the shoulder parallel to the brachial artery.

The major superficial veins of the upper limb are the cephalic, median cubital and basilic veins. The cephalic vein arises from the dorsal venous network of the hand and passes the elbow anteriorly, continuing up the upper arm to the shoulder. The basilic vein follows a similar path but is located medially to the cephalic vein. At the elbow, the basilic and cephalic veins are linked by the median cubital vein, from which blood is often drawn.

At the shoulder, the basilic vein passes deep into the arm and merges with the brachial veins to form the axillary vein, to which the cephaliac vein merges, forming the subclavian vein.

Veins of the Thorax

The veins of the thorax drain deoxygenated blood from the thorax region for return to the heart

Key Points

Major veins of the thorax include the superior and inferior vena cava.

The superior vena cava is formed by the left and right brachiocephalic veins, which receive blood from the upper limbs, head and neck.

The inferior vena cava returns blood from the abdomen and lower limbs. The hepatic veins of the liver and renal veins of the kidney drain directly into the inferior vena cava.

Key Terms

- supreme intercostal vein: A paired vein that drains the first intercostal space on its corresponding side.

- internal thoracic vein: Drains the chest wall and breasts.

- inferior vena cava: Returns blood from the abdomen and lower limbs to the right atrium of the heart.

- superior vena cava: Formed from the left and right brachiocephalic veins, this vein returns deoxygenated blood from the upper half of the body and carries blood from the upper limbs, head, and neck via the thyroid and jugular veins.

Veins of the Thorax: The veins of the thorax are shown in blue.

Two venae cavae return deoxygenated blood from the systemic circulation to the right atrium of the heart.

The superior vena cava, formed from the left and right brachiocephalic veins, returns deoxygenated blood from the upper half of the body and carries blood from the upper limbs, head, and neck via the thyroid and jugular veins. It is joined just before entering the heart by the azygos vein, which runs up the right side of the thoracic vertebral column and transports blood from the external thoracic cavity.

The internal thoracic vein is a vessel that drains the chest wall and breasts. Bilaterally, it arises from the superior epigastric vein, accompanies the internal thoracic artery along its course, and terminates in the brachiocephalic vein.

The supreme intercostal vein is a paired vein that drains the first intercostal space on its corresponding side. It usually drains into the brachiocephalic vein.

The inferior vena cava returns blood from the abdomen and lower limbs to the right atrium of the heart. The renal veins from the kidney and hepatic veins of the liver drain directly into the inferior vena cava. Additionally, the superior and inferior phrenic veins drain the diaphragm and usually open into the internal mammary vein and inferior vena cava, respectively.

Veins of the Abdomen and Pelvis

The major veins of the abdomen and pelvis return deoxygenated blood from the abdomen and pelvis to the heart.

Key Points

The external iliac vein, the upward continuation of the femoral vein, passes upward along the pelvis and ends to form the common iliac vein.

The tributaries that feed into the external iliac vein include the inferior epigastric, deep iliac circumflex, and pubic veins.

The inferior epigastric vein refers to the vein that drains into the external iliac vein and arises from the superior epigastric vein.

Key Terms

- External iliac vein: Large veins that connect the femoral veins to the common iliac veins

- Common iliac vein: Formed by the external iliac veins and internal iliac veins.

A number of veins remove deoxygenated blood from the abdomen and pelvis. The external iliac vein, the upward continuation of the femoral vein, passes upward along the pelvis and ends to form the common iliac vein.The tributaries of the external iliac vein are the inferior epigastric, deep iliac circumflex, and pubic veins.

The internal iliac vein begins near the upper part of the greater sciatic foramen, the large opening at the rear of the pelvis, passes upward behind and slightly medial to the internal iliac artery and, at the brim of the pelvis, joins with the external iliac vein to form the common iliac vein.

Veins of the abdomen and lower limbs: The veins of the abdomen and lower limb include the inferior vena cava, the common iliac veins, the external iliac veins, and their tributaries.

The left and right common iliac veins come together in the abdomen at the level of the fifth lumbar vertebra, forming the abdominal vena cava. They drain blood from the pelvis and lower limbs.

The superior epigastric vein refers to a blood vessel that carries deoxygenated blood and drains into the internal thoracic vein. It anastomoses with the inferior epigastric vein at the level of the umbilicus and drains the anterior part of the abdominal wall and some of the diaphragm.

The inferior epigastric vein refers to the vein that drains into the external iliac vein and arises from the superior epigastric vein.

The deep circumflex iliac vein is formed by the union of the venae comitantes of the deep iliac circumflex artery and joins the external iliac vein about 2 cm above the inguinal ligament.

Veins of the Lower Limbs

The deep veins of the lower extremity have valves for unidirectional flow and accompany the arteries and their branches.

Key Points

The tibial veins unite to form the popliteal vein.

The femoral vein is the ascending part of the popliteal vein.

The femoral vein accompanies the femoral artery into the thigh. It is later joined by the great saphenous vein forming the external iliac vein.

Key Terms

- popliteal vein: Derived from the merging of the tibial veins it forms the femoral vein mid-thigh.

- great saphenous ve: A long vein that runs the length of the leg before joining the femoral vein to form the external iliac vein.

- Femoral Vein: A blood vessel that accompanies the femoral artery in the thigh. It merges with the great saphenous vein to form the external iliac vein.

- Tibial Vein: Blood vessel of the calves which return blood from the foot, ankle, and calf and merges into the popliteal vein behind the knee.

The deep veins of the leg accompany the arteries and their branches and possess numerous valves that aid in unidirectional blood flow. The musculature of the leg is key in generating pressure in the veins to prevent pooling.

The posterior and anterior tibial veins return blood from the calf, ankle, and foot and merge into the popliteal vein behind the knee. The popliteal vein then carries blood from the knee joint up through the thigh. Mid-thigh, it becomes the femoral vein, which is closely associated with the femoral artery. The femoral vein merges with the great saphenous vein in the groin to form the external iliac vein.

(a) Veins of the lower extremities and (b) Veins of the lower extremities: The great saphenous vein and its tributaries, shown in blue, drain blood from the lower limbs. The popliteal vein, shown here in blue, extends from the hip to the knee and helps drain blood from the lower extremities.

Running the full length of the leg, making it the longest vein in the body, the great saphenous vein is a superficial vein that returns blood from the foot and superficial muscles of the leg before merging with the femoral vein to form the external iliac vein.

References