How do you strengthen your trapezius muscle?/Trapezius myalgia (TM) is the complaint of pain, stiffness and tightness of the upper trapezius muscle. It is characterized by acute or persistent neck-shoulder pain.[rx]

TM is not a medical disorder or disease but rather a symptom of an existing underlying condition. The pain in the muscle can last a few days or longer.

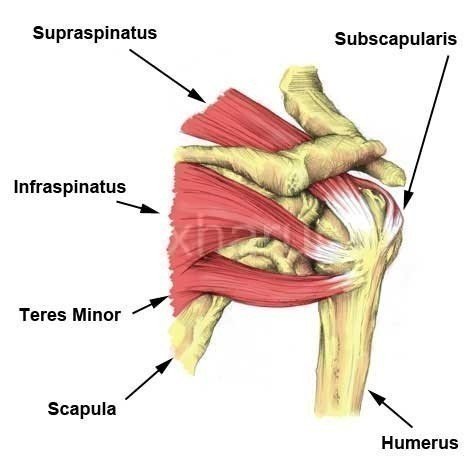

The trapezius muscle is a large superficial back muscle that resembles a trapezoid. It extends from the external protuberance of the occipital bone to the lower thoracic vertebrae and laterally to the spine of the scapula. The trapezius has upper, middle, and lower groups of fibers. The trapezius has three functional parts: an upper (descending) part which supports the weight of the arm; a middle region (transverse), which retracts the scapula; and a lower (ascending) part which medially rotates and depresses the scapula.

Trapezius muscle, the large, superficial muscle at the back of the neck and the upper part of the thorax, or chest. The right and left trapezius together form a trapezium, an irregular four-sided figure. It originates at the occipital bone at the base of the skull, the ligaments on either side of the seven cervical (neck) vertebrae (ligament nuchae), and the seventh cervical and all thoracic vertebrae. It is inserted on the posterior of the clavicle (collarbone) and on the spine of the scapula (shoulder blade). Its chief action is the support of the shoulders and limbs and rotation of the scapula necessary to raise the arms above the shoulder level.

Anatomy of Trapezius Muscle Tendonitis

Nerve supply

Motor function is supplied by the accessory nerve. Sensation, including pain and the sense of joint position (proprioception), travel via the ventral rami of the third (C3) and fourth (C4) cervical nerves. Since it is a muscle of the upper limb, the trapezius is not innervated by dorsal rami despite being placed superficially in the back.

[stextbox id=’alert’]

| Nerve | Referred Distribution |

|---|---|

| C1-2 | Occipital region of the head |

| C3 | Temporal region of the head |

| C4,5 | Shoulder |

| C6, 7 8, T1 | Arm and hand |

| Origins | Descending part: Medial third of superior nuchal line, External occipital protuberance, Spinous processes of cervical vertebrae/Nuchal ligament

Transverse part – Broad aponeurosis at spinous processes of vertebrae T1-T4 (or C7-T3) Ascending part – Spinous processes of vertebrae T5-T12 (or T2-T12) |

| Insertions | Descending part – Lateral third of the clavicle

Transverse part = Medial aspect of acromion, Superior crest of the spine of the scapula Ascending part – Medial end of the spine of the scapula |

| Innervation | Motor – Accessory nerve (CN XI)

Sensory – Anterior rami of spinal nerves C3-C4 (via cervical plexus) |

| Action | Descending part – Scapulothoracic joint: Draws scapula superomedially; Atlantooccipital joint/ upper cervical vertebrae: Extension of head and neck, Lateral flexion of head and neck (ipsilateral); Altantoaxial joint: Rotation of head (contralateral);

Transverse part: Scapulothoracic joint: Draws scapula medially Ascending part: Scapulothoracic joint: Draws scapula anteromedially (All parts support scapula) |

| Blood supply | Occipital artery (upper part), superficial or transverse cervical artery (middle part), dorsal scapular artery (lower part) |

[/stextbox]

Blood Supply and Lymphatics

Two main variants to the vascular supply to the trapezius develop from three common sources. The most common variant involves the main supply of blood from the transverse cervical artery, with collateral supply from the dorsal scapular artery for the superior portion, and the posterior intercostal arterial branches from the deep portions. The second less common variant has more blood supply from the dorsal scapular artery. [rx]

Function

Contraction of the trapezius muscle can have two effects: movement of the scapulae when the spinal origins are stable, and movement of the spine when the scapulae are stable. Its main function is to stabilize and move the scapula.

Causes of Trapezius Muscle Tendonitis

There are several possible causes of trapezius pain, including:

- Overuse – Pain in the trapezius often develops due to overuse. Repetitive activities that involve the shoulders can put stress on the muscle. These activities may include lifting heavy objects or participating in specific sports, such as swimming.

- Poor posture – Prolonged poor posture can place added stress on the trapezius. Hunching over a desk or computer keyboard for many hours, for example, can result in the muscle becoming shortened and tight.

- Trauma – Injuries to the trapezius, such as a muscle tear from placing too much force on the muscle, can lead to pain.

- Repetitive stress – Repeating the same shoulder motions, again and again, can stress your trapezius muscles and tendons. Baseball, tennis, rowing, and weightlifting are examples of sports activities that can put you at risk for overuse tears. Many jobs and routine chores can cause overuse of tears, as well.

- Lack of blood supply – As we get older, the blood supply in our trapezius lessens. Without a good blood supply, the body’s natural ability to repair tendon damage is impaired. This can ultimately lead to a tendon tear.

- Bone spurs – As we age, bone spurs (bone overgrowth) often develop on the underside of the acromion bone. When we lift our arms, the spurs rub on the trapezius muscle. This condition is called shoulder impingement, and over time will weaken the tendon and make it more likely to tear.

- Sudden forceful fall down

- Road traffic accident

- Falls – Falling onto an outstretched hand is one of the most common causes of injury.

- Sports injuries – Many Injury occurs during contact sports or sports in which you might fall onto an outstretched hand — such as in-line skating or snowboarding.

- Motor vehicle crashes – Motor vehicle crashes can cause necks of femur fracture to break, sometimes into many pieces, and often require surgical repair.

- Have osteoporosis – a disease that weakens your bones

- Eave low muscle mass or poor muscle strength – or lack agility and have poor balance (these conditions make you more likely to fall)

- Walk or do other activities in the snow or on the ice – or do activities that require a lot of forwarding momenta, such as in-line skating and skiing

- Wave an inadequate intake of calcium or vitamin D

- Football or soccer, especially on artificial turf

- Rugby

- Horseback riding

- Hockey

- Skiing

- Snowboarding

- In-line skating

- Jumping on a trampoline

Symptoms of Trapezius Muscle Tendonitis

It can contribute to the following pain symptoms. Click on the corresponding link to learn how to achieve relief.

- Neck Pain – may be chronic or recent in onset. It may be confined to the neck or radiate to the arms. It may be described as mild or severe and dull or sharp and better or worse with certain physical maneuvers. These characteristics will help localize the issue and point towards its origin. On occasion, the distribution of pain will suffice to establish the correct diagnosis.

- Headache – frequently accompanies cervical spine pathology and maybe the most prominent complaint. The headache is usually daily, in the back of the skull and radiates forwards over the temples. It is generally mild and relieved with minor pain medications. When chronic, it can be quite severe and mistaken for “migraine”.

- Numbness – into the arm in a particular location provides clues as to which nerve is involved and, perhaps, also the exact location where the nerve is involved.

- Weakness – is less likely noticeable to the patient unless it is profound, although the neurologist will inquire if there are any particular muscles or groups of muscles that don’t seem to work well. Weakness in the arms is generally less noticeable than in the legs. Fatigue of certain motions may be more readily recognized and reported as a weakness.

- Bowel, Bladder, Gait, and Balance – difficulties are clues to spinal cord injury and symptoms of this nature are quite important.

- Episodes of pain are often experienced causing pain in the neck.

- There may also be difficulty in the movement of the neck due to spasms.

- After a prolonged period of pain due to trapezius, the pain becomes more troublesome and may appear often by the slightest trigger or strain in the trapezius.

- Pain and tightness in the neck and trapezius muscle may last for usually 3 to 5 days in an individual.

- During this phase of the trapezius, the patient might also complain of pain in their arms and hands.

- In some conditions of the trapezius, particularly long-standing ones, chronic muscle spasm may also lead to nerve compression. This often results in further symptoms of trapezius like tingling, numbness or even weakness in the arms, hands, and fingers on the affected side.

- Stiff neck

- Pain in the area between the shoulder blades

- Pain on the shoulder blade

Diagnosis of Trapezius Muscle Tendonitis

Testing of the accessory nerve is done as follows

ALWAYS inform the patient of what you will be doing, after introducing yourself and taking a detailed clinical history

- When examining a patient, ensure you just observe the patient and try to identify if there is any obvious deformity or asymmetry of the shoulder and neck region. It may be that you will see an obvious weakness or asymmetrical position of the patient’s neck and/or upper limbs.

- First, you can assess the sternocleidomastoid.

- You can ask the patient to rotate their head to look to the left- and right-hand sides to identify any obvious abnormality.

- Then, ask the patient to look to one side and test the muscle against resistance.

- For example, if the patient looks to the right side, place the ball of your hand on their left mandible

- Ask the patient to press into your hand.

- Repeat this on the opposite side. Then, you need to assess the trapezius.

- First, you can ask the patient to raise their shoulders, as in shrugging.

- Observe any gross abnormality.

- Then while the patient is raising their shoulders, gently press down on them as they lift their shoulders.

- Assess any weakness which may be present, noting which side is affected.

Physical Examination

- Motor Function – of almost all of the muscles in both the arms and legs are tested. The maximum power that each muscle can generate and the loss of muscle bulk (atrophy) are assessed.

- Sensory Function – is tested with either a pin-prick or light-touch method, looking for areas of numbness, tingling or burning.

- Reflex Activity – of the arms and legs is tested with the rubber hammer to provide insight to the nerve, spinal cord, and muscle function.

- Gait Assessment – is reviewed for balance and pattern of muscle power.

- The coordination of both arms and legs is reviewed for both dexterity and balance.

- Range of Motion – of the spine, both passively and actively, is performed while assessing the musculature and identifying whether any nerve, spinal cord or pain difficulties emerge.

Electrodiagnostic Testing

Electromyography (EMG) – is a test that reveals whether certain muscles are receiving the correct electrical signals from their nerves. There are two parts to this test:

- Nerve conductions are shocks that permit the reader to determine the rate of speed that the nerve is sending messages, and thus its general health.

- Needle electrode testing is performed by sampling several muscles with an electrode to determine whether the muscles are receiving the correct electrical signals from any single nerve. When a specific group of muscles does not test normally, this informs the neurologist as to where the problem lies and the severity of the injury.

Radiographic Imaging

- X-ray – is the easiest means to image the spine. X-ray reveals alignment and degenerative changes of the bones. The spaces for the discs are seen as well, but no pictures are seen of the spinal cord, nerves or actual disc material. Unsuspected bony pathology, such as fractures, dislocations, and cancer metastases, are quickly identified with an x-ray.

- CT Scan – is useful for cross-sectional imaging of the spine and increased image detail of the spinal cord, nerves, and discs, but less so than MRI imaging.

- MRI – is currently the best means of visualizing all of the important structures of the cervical spine. With a good MRI study, considerable detail is available of the bones, discs, spinal cord, ligaments and even the nerves. MRI studies are most likely the major determinant of the pathology causing the cervical spine difficulties, whatever their nature.

- Blood work – may be ordered if suspicion of spinal cord disease is present. Also, certain forms of arthritis (Rheumatoid) may be detected with blood work.

- Bone density assessment – assists in the diagnosis of a loss of calcium as seen in osteopenia and osteoporosis, conditions that weaken the bone structure everywhere.

- Ultrasound such as high-resolution ultrasonography (HRUS) – has been used to confirm the target nerve and visualize the structures surrounding the nerve. Ultrasound is meaningful in detecting some change to the muscles, such as atrophy, and reducing possible damage during the administration of injections and medication to the affected area by guiding to correct targeted area while visualizing with the ultrasound. Ultrasonography is not helpful in detecting the actual transaction of the nerve.[rx][rx]

- Electromyography (EMG) – and nerve conduction studies are unnecessary for the diagnosis; however, it would be helpful to distinguish and quantify the degree of damage by doing serial EMGs. Electromyography (EMG) has shown that the trapezius muscle is the main muscle responsible for shoulder elevation and, by means of its upper bundle, it participates in the arm elevation movement. Nonetheless, this movement also involves the participation of the deltoid, supra-spinal, and infra-spinal muscles.

Treatment of Trapezius Muscle Tendonitis

In Acute Stage

- Apply ice – after you get home from the hospital (regardless if you had surgery or not), you should apply a bag of crushed ice (or something cold) to your injured in order to reduce the swelling and numb the pain. Ice therapy is effective for acute (recent) injuries that involve swelling because it reduces blood flow by constricting local blood vessels. Apply the crushed ice to your injured area for 15 minutes three to five times daily until the soreness and inflammation eventually fade away or Ice can be applied for 15 minutes every 2 hours for the first day or two. From then on the frequency can be gradually reduced over a period of days.

- Rest – Continuing to use your arm when it is painful prevents your tear from healing.

- Avoiding activities that aggravate the pain – like overhead reaching or reaching behind the back

- Keep your injured parts in a comfortable position – in front of and close to your body (avoid an arm sling, as you risk the development of a frozen shoulder)

- Ice to reduce initial inflammation in tendonitis – (apply a cold pack to shoulder for 15 to 20 minutes every four to six hours)

- For a partial rupture – complete rest is best. Your shoulder should be immobilized in a sling or similar. See a sports injury specialist or doctor who can advise on treatment and rehabilitation.

- When your injury – has healed and you are pain-free, begin rehabilitation exercises. These should include mobility, strengthening and functional or sports specific exercises that should be done.

-

Lightly exercise after the pain fades – after a couple of weeks when the swelling has subsided and the pain has faded away, remove your arm sling for short periods and carefully move in all different directions. Don’t aggravate the necks but gently reintroduce movements to the involved joints and muscles. Start cautiously, maybe starting with light and then progress to holding light weights (five-pound weights to start).

- Practice stretching and strengthening exercises – of the fingers, leg if your doctor recommends them.

- A splint – which you might use for a few days to a week while the swelling goes down; if a splint is used initially, a cast is usually put on about a week later.

- A cast – which you might need for six to eight weeks or longer, depending on how bad the break is (you might need a second cast if the first one gets too loose after the swelling goes away.)

- Iontophoresis, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulations (TENS) – and other similar therapy modalities in the presence of FTTs, the committee reported a moderate recommendation grade for exercises and/or NSAIDs in the presence of RCS symptoms in the absence of FTTs.

- Get a referral to physical therapy – Once you’ve recovered and able to remove your arm sling splint for good, you’ll likely notice that the muscles surrounding your shoulder joint look smaller and feel weaker. That’s because muscle tissue atrophies without movement. If this occurs, then you’ll need to get a referral for some physical rehabilitation. Rehab can start once you are cleared by your orthopedist, are pain-free, and can perform all the basic arm and necks of femur fracture movements. A physiotherapist or athletic trainer can show you specific rehabilitation exercises and stretches to restore your muscle strength, joint movements, and flexibility.

- For RC tendonitis – the most utilized injection includes one into the subacromial space. Patients can experience symptomatic relief almost instantaneously after the injection is given, allowing them to participate in subsequent PT therapy sessions ideally.

Medication

- Antibiotic – Cefuroxime or Azithromycin, or Flucloxacillin or any other cephalosporin/quinolone antibiotic must be used to prevent infection or clotted blood remove to prevent furthers swelling and edema. Antibiotics and tetanus vaccination may be used if the bone breaks through the skin creating immunization.

- NSAIDs – Prescription-strength drugs that reduce both pain and inflammation. Pain medicines and anti-inflammatory drugs help to relieve pain and stiffness, allowing for increased mobility and exercise. There are many common over-the-counter medicines called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). They include and Ketorolac, Aceclofenac, Naproxen, Etoricoxib.

- Corticosteroids – Also known as oral steroids, these medications reduce inflammation.

- Cortisone injections – First-line nonoperative management also includes the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs) medications in conjunction with PT modalities to rapidly reduce pain.

- Muscle Relaxants – These medications provide relief from associated muscle spasms or injury

- Neuropathic Agents – Drugs(pregabalin & gabapentin) that address neuropathic—or nerve-related—pain. This includes burning, numbness, and tingling.

- Opioids – Also known as narcotics, these medications are intense pain relievers that should only be used under a doctor’s careful supervision.

- Topical Medications – These prescription-strength creams, gels, ointments, patches, and sprays help relieve pain and inflammation through the skin.

- Calcium & vitamin D3 – To improve bone health and healing fracture. As a general rule, men and women age 50 and older should consume 1,200 milligrams of calcium a day, and 600 international units of vitamin D a day.

- Glucosamine & Diacerein, Chondroitin sulfate – can be used to tightening the loose tendon, cartilage, ligament, and cartilage, ligament regenerates cartilage or inhabits the further degeneration of cartilage, ligament.

- Dietary supplement -to remove general weakness & healing and improved health.

- Antidepressants – A drug that blocks pain messages from your brain and boosts the effects of endorphins (your body’s natural painkillers).

- Menthol – provides deep penetrating pain relief with a nice cooling sensation

- Vitamin B1, B6, B12– promotes normal nerve function

- Vitamin E – anti-inflammatory, enhances circulation, hydrates the skin

- Aloe vera – anti-inflammatory properties, soothes the skin

- Tea Tree – enhances the penetration of ingredients

- MSM – supports healthy connective tissues, anti-inflammatory

- Ilex Leaf Extract – increases circulation, skin conditioner

- Botulinum toxin injections – to her trapezius muscles, which considerably reduced pain and spasm. This clinical improvement lasted 3 months. Ongoing injections as required are planned.

Physical Therapy of Trapezius Muscle Tendonitis

Raising awareness for at-risk groups of people

- Repetitive movement jobs

- Sedentary jobs (computer work

- High work demands

- Work posture

- Vibration

- Stress

- Low activity level outside of work

- Gender (women)

Exercise Therapy

Different forms of exercise are recommended for acute or persistent trapezius. [rx] Physical activity and exercise have been proven to give the most immediate and long-term pain relief in patients with TM[rx].

- The neck bends – Look straight ahead with your shoulders relaxed. While lowering your right shoulder, bend your neck to the left, as if you’re trying to touch your left ear to your left shoulder. Hold for 20 seconds and repeat on the opposite side.

- Scapula settings – Lie on your stomach. You can use a pillow or towel underneath your forehead to help you relax. With your arms flat at your sides, pull your shoulder blades together and back as far as you can go. Hold for 10 seconds and repeat 10 times.

- Shoulder shrugs – Stand tall and hold dumbbells to the side in each hand. Elevate the shoulders while focusing on contracting the upper trapezius muscle. The subject is standing erect and holding the dumbbells to the side, then elevates the shoulders while focusing on contracting the upper trapezius muscle.

- One-arm row – The subject bends their torso forward to approximately 30° from horizontal with one knee on the bench and the other foot on the floor. The subject now pulls the dumbbell towards the ipsilateral lower rib, while the contralateral arm is maintained extended and supports the body on the bench.

- Upright row – The subject is standing erect and holding the dumbbells while the arms are hanging relaxed in front of the body. The dumbbells are lifted towards the chest in a vertical line close to the body while flexing the elbows and abducting the shoulder. The elbows are pointing out- and upwards.

- Reverse flies – The subject is prone on a bench at a 45° angle from horizontal and the arms pointing towards the floor. The dumbbells are raised until the upper arm is horizontal, while the elbows are in a static slightly flexed position (~5°) during the entire range of motion.

- Lateral raise – The subject is standing erect and holding the side of the dumbbell, and then abducts the shoulder joint until the upper arm is horizontal. The elbows are in a static slightly flexed position (5°) during the entire range of motion. Exercise has been shown to increase blood flow and therefore oxygenation to areas of the body with increased anaerobic muscle metabolism.

Stretches

- Stretching can help keep the trapezius muscle from getting too tight. It may also prevent or relieve pain. When stretching, it is important to move in and out of the stretch gently, avoiding jerky movements and bouncing. Hold the stretch for about 15 to 30 seconds. A stretch should cause tension but no pain, so a person should avoid forcing any stretches. Below are some trapezius stretches to try.

Cat stretch

To do the cat stretch

- Get into position on all fours on the floor.

- Inhale and curl the spine up toward the ceiling while contracting the abdominal muscles.

- Hold the position for 15 seconds.

- Exhale and allow the belly to sink toward the floor, arching the back.

Ear-to-shoulder

To do an ear-to-shoulder stretch

- Sit up straight in a chair.

- Slowly bend the head over to the left side as though trying to touch the ear to the shoulder.

- Place the left hand on the head and gently pull it down toward the shoulder for a deeper stretch.

- Hold the stretch for 20 seconds.

- Release the head and perform the same stretch on the right side.

Hug stretch

To do a huge stretch

- Stand up straight.

- Reach the right arm across the chest and hold the left shoulder. Do the opposite on the other side to hold the right shoulder with the left hand.

- Press down on the left shoulder with the right hand while leaning the head to the right.

- Hold the stretch for about 20 seconds.

- Repeat on the other side.

Dry needling

- Dry needling is a technique that involves inserting short, fine needles into the skin at specific trigger points. Proponents of dry needling claim that inserting the needles into trigger points release muscle knots and may decrease pain.

A small 2018 study involving 40 adult athletes with shoulder pain found that dry needling in the upper trapezius muscle decreased pain severity.

Applying ice and heat

- Both hot and cold therapy may decrease the discomfort of muscle pain. Applying ice can help reduce inflammation and pain in the trapezius.

- Heat can effectively reduce muscle spasms, increase blood flow to the area, and promote healing.

Taping

- The use of kinesiology tape may also help ease trapezius pain. This technique involves applying a stretchy elastic tape over the painful area to decrease pressure on the muscle.

- One small, short-term study recruited 73 participants with trapezius pain. A pain assessment took place before and after kinesiology taping. The participants also had a 24-hour follow-up assessment.

- The study found that kinesiology taping significantly reduced subjective pain sensation.

- Although the study was limited, kinesiology taping is a low-risk solution that may provide some relief.

- The possible presence of psychosocial causative factors in patients with TM should be considered from the outset. Explanation of pain and the influence of psychosocial factors should also be included in the treatment of TM alongside exercise therapy. [rx]

Manual therapy

- There is moderate evidence available for short-term relief of myofascial trigger points by Transcutaneous Electro Nerve Stimulation (TENS), acupuncture and magnet or laser therapy.[rx][rx]

- Some studies have shown that in the short term acupuncture/dry needling can have the largest effect on pain. There is no evidence of effective treatment to reduce pain in the intermediate and long term periods.[rx]

- There is conflicting evidence as to whether ultrasound therapy is no more effective than a placebo or somewhat more effective than other therapies in the treatment of myofascial trigger points. Ultrasound can, therefore, be used as a therapeutic modulation but is not recommended.[rx]

Biofeedback training

- Biofeedback training can also be useful in the treatment of work-related neck and shoulder pain. A study has shown that six weeks of biofeedback training resulted in less pain and neck disability than active and passive treatment, which remained at 6 months post-intervention in the control.

- Ischaemic compression, a stretch of the upper trapezius muscle and transverse friction massage are manual techniques to help patients with TM. These techniques appear to have an instant improvement in pain. Long-term effects have not yet been well investigated.

References

Have the client stand with her legs at least shoulder-width apart so she is stable while doing the test. Place one hand on her upper arm just above the elbow and press the upper arm into the body for stability. With the person’s arm bent in front at a right angle, place your other hand on the outside of her lower arm just above the wrist. Now ask the client to push laterally or outward toward you while you resist the push with equal force (Image 1A). This test is done at 90 degrees to the body, first, but also may need to be done at 30 degrees (Image 1B) and at 135 degrees (Image 1C) for more precise testing. The different angles put stress on different parts of the tendon. A positive test, when pain is felt, indicates that the infraspinatus is injured.

Have the client stand with her legs at least shoulder-width apart so she is stable while doing the test. Place one hand on her upper arm just above the elbow and press the upper arm into the body for stability. With the person’s arm bent in front at a right angle, place your other hand on the outside of her lower arm just above the wrist. Now ask the client to push laterally or outward toward you while you resist the push with equal force (Image 1A). This test is done at 90 degrees to the body, first, but also may need to be done at 30 degrees (Image 1B) and at 135 degrees (Image 1C) for more precise testing. The different angles put stress on different parts of the tendon. A positive test, when pain is felt, indicates that the infraspinatus is injured.