Biceps Tendinopathy is a relatively common ailment that typically presents as pain, tenderness, and weakness in the tendon of the long head of the biceps brachii. Though it is often associated with degenerative processes of the rotator cuff and the joint, this is not always the case, thus, the etiology remains considerably unknown. There has been recent interest in elucidating the pathogenesis of tendinopathy, since it can be an agent of chronic pain, and is difficult to manage. The purpose of this article is to critically evaluate relevant published research that reflects the current understanding of pain and how it relates to biceps tendinopathy.

Biceps Brachii Muscles is a large, thick muscle on the ventral portion of the upper arm. The muscle is composed of a short head (caput breve) and a long head (caput longum). The short head originates from the tip of the coracoid process, and the long head originates from the supraglenoid tubercle (tuberculum supraglenoidale) of the glenoid/scapula. Both heads course distally and become a confluent muscle belly before tapering across the anterior aspect of the elbow, eventually inserting on the radial tuberosity and the fascia of the forearm via the bicipital aponeurosis. [rx][rx] The antagonist of the biceps muscle is the triceps brachii muscle.[rx][rx][rx]

Anatomy of Biceps Tendinopathy

The LHBT origin, on average, is 9 cm in length.[rx] The tendon is widest at its labral origin, which is primarily posterior about 50% of the time.[rx] In 20% of cases, the origin is directly at the supraglenoid tubercle, and the remaining 30% of the time its origin is seen as a combination of the 2 sites.[rx] The tendon itself is intra-articular yet extra-synovial, and it progressively gets narrower as it passes obliquely from its origin and heads toward the bicipital groove. As it exits the distal bicipital groove in the upper arm, the LHBT joins the short head of the biceps tendon (SHBT) as both transitions into their respective muscle bellies in the central third of the upper arm. After crossing the volar aspect of the elbow, the biceps brachii inserts on the radial tuberosity and medial forearm fascia. The latter occurs via the bicipital aponeurosis.[rx]

[stextbox id=’black’]

|

The biceps is a two-headed muscle and is one of the chief flexors of the forearm. Here is the left side, seen from the front.

|

|

| Details | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | baɪsɛps |

| Origin | Short head: coracoid process of the scapula. Long head: supraglenoid tubercle |

| Insertion | Radial tuberosity and bicipital aponeurosis into deep fascia on medial part of forearm |

| Artery | Brachial artery |

| Nerve | Musculocutaneous nerve (C5–C7) |

| Actions |

|

| Antagonist | Triceps brachii muscle |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | musculus biceps brachii |

| TA | A04.6.02.013 |

| FMA | 37670 |

| Anatomical terms of muscle | |

| Origin | Long head – supraglenoid tubercle of the scapula Short head – apex of the coracoid process of the scapula |

| Insertion | Radial tuberosity of the radius

Deep fascia of forearm (insertion of the bicipital aponeurosis) |

| Innervation | Musculocutaneous nerve (C5- C6) |

| Function | Flexion and supination of the forearm at the elbow joint, weak flexor of the arm at the glenohumeral joint |

The flexors of the shoulder

| Muscle | Nerve | Spinal nerve root |

|---|---|---|

| Coracobrachialis | Musculocutaneous | C5, C6 |

| Pectoralis major | Pectoral | C5–C8 |

| Deltoid (anterior portion) | Axillary | C5 (C6) |

| Subscapularis | Subscapular | C5–C8 |

| Biceps brachii | Musculocutaneous | C5, C6 |

[/stextbox]

Diagnosis of Biceps Tendinopathy

Grading

While histologic grading of the severity of tendinopathic changes remains separate from the clinical presentation and MRI and/or intra-operative findings, there are some noteworthy pathologic patterns associated with increasing grades of severity of tendinopathy.[rx][rx]

Grade 0

-

Tenocytes are normal in appearance

-

Myxoid degenerative material not present

-

Collagen remains arranged in tight, cohesive bundles

-

Blood vessels arranged inconspicuously between collagen bundles

Grade I

-

Tenocytes are rounded

-

Myxoid degenerative material present in small amounts between collagen bundles

-

Collagen remains arranged in discrete bundles, but a slight separation between bundles becomes apparent

-

Capillary clustering is evident (less than 1 cluster per 10 high-power fields)

Grade II

-

Tenocytes are rounded and enlarged

-

Myxoid degenerative material evident in moderate to large amounts

-

Collagen bundles lose discrete organization as the separation between individual fibers and bundles increases

-

Capillary clustering is increased (1 to 2 clusters per 10 high-power fields)

Grade III

-

Tenocytes are rounded and enlarged with abundant cytoplasm and lacuna

-

Myxoid degenerative material abundant

-

Collagen disorganized, loss of microarchitecture

-

Capillary clustering is increased (greater than 2 clusters per 10 high-power fields)

Bicipital groove palpation – Direct palpation over the patient’s bicipital groove elicits a painful response in the setting of pathology.

Speed’s test – A positive test consists of pain elicited in the bicipital groove when the patient attempts to forward elevate the shoulder against examiner resistance; the elbow is slightly flexed, and the forearm is supinated.

Uppercut test – The involved shoulder is positioned at neutral, the elbow is flexed to 90 degrees, the forearm is supinated, and the patient makes a fist. The examiner instructs the patient to perform a boxing “uppercut” punch while placing his or her hand over the patient’s fist to resist the upward motion. A positive test is pain or a painful pop over the anterior shoulder near the bicipital groove region.

Ferguson’s test – The arm is stabilized against the patient’s trunk, and the elbow is flexed to 90 degrees with the forearm pronated. The examiner manually resists supination while the patient also externally rotated the arm against resistance. A positive test is noted if the patient reports pain over the bicipital groove and/or subluxation of the LHB tendon.

Dynamic tests for bicipital groove symptoms

-

The examiner brings the patients shoulder to 90 degrees of abduction and 90 degrees of external rotation. The examiner passively rotates the shoulder at this position in an attempt to elicit the patient-reported audible “popping” or “clicking” sensations. Sometimes passively maneuvering the shoulder from the extension to cross-body plan is helpful in eliciting instability symptoms.

-

At the 90/90 shoulder abduction/external rotation position, the patient is asked to “throw forward” while the examiner resists this forward motion. A positive test for groove pain must be localized to the anterior aspect of the shoulder to enhance diagnostic sensitivity and specificity.

Other Changes Associated with Tendinopathy

Tenosynovium

-

Irrespective of histologic grade of tendinopathy, the surrounding bicipital sheath/synovium demonstrates varying degrees of synovial hypertrophy, hyperplasia, and proliferation

Low-Grade Degenerative Tendinopathy

-

Total cellularity (cell density, cells/ mm): Minimal increase

-

Apoptotic index (percent relative to the total number of cells counted): Minimal increase

Moderate Grade Degenerative Tendinopathy

-

Total cellularity (cell density, cells/ mm): Peak increase

-

Apoptotic index (percent relative to the total number of cells counted): Moderate increase

Severe Grade Degenerative Tendinopathy

-

Total cellularity (cell density, cells/ mm): Decreases

-

Apoptotic index (% relative to the total number of cells counted): Peak increase

Histologic studies have consistently reported that irrespective of patient age, the severity of symptoms, and duration of symptoms, acute inflammatory changes are rarely evident upon histologic specimen analysis.

In 2004, Habermeyer and colleagues identified 4 different subtypes of soft tissue injury groups. These types were similar to those described by Braun and colleagues, also noting 4 different types of soft tissue pulley lesions during shoulder arthroscopy.[rx]

-

Type I – SGHL lesion, isolated

-

Type II – SGHL lesion and partial articular-sided supraspinatus tendon tear

-

Type III – SGHL lesion and deep surface tear of the subscapularis tendon

-

Type IV – SGHL lesion combined with a partial articular-sided supraspinatus and subscapularis tendon tears

Bennett’s classification system subdivides biceps soft tissue pulley lesions into types I to V.[rx]

-

Type I – Intra-articular subscapularis injury

-

Type II – Medial band of CHL incompetent

-

Type III – Subscapularis and the medial band of the CHL are both compromised; LHBT dislocates intra-articularly, medially

-

Type IV – A lateral band of CHL along with a leading-edge injury of the subscapularis; Can lead to LHBT dislocation anterior to the subscapularis

-

Type V – All soft tissue pulley components are disrupted

Walch classified biceps pulley lesions based on the observed LHBT instability pattern.[rx]

-

Type I – SGHL/CHL injury; Superior LHBT subluxation at the proximal groove entrance; Subscapularis remains intact, preventing frank LHBT dislocation

-

Type II – At least partial subscapularis injury is seen in association with the onset of pathology; Medial LHBT subluxation or dislocation

-

Type III – Secondary to proximal humerus fracture; usually a lesser tuberosity fracture that is prone to malunion or nonunion

Ultrasound (US) is highly operator-dependent but is touted as a fast, cost-effective tool for diagnosing LHBT pathology. Characteristic findings include tendon thickening, tenosynovitis, and synovial sheath hypertrophy, and fluid surrounding the tendon in the bicipital groove. The ability to perform a dynamic examination increases the sensitivity and specificity for detecting subtle instability.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful in evaluating the LHBT, bicipital groove, and any fluid or edema that may be indicative of pathology. MRI helps define other associated shoulder pathologies, and in the setting of LHBT instability, particular attention should be given to evaluating for concomitant subscapularis injury.

Many studies have suggested MR arthrography (MRA) as the best imaging modality for the detection of biceps soft tissue pulley lesions. Walch previously described the “pulley sign” on MRA, suggesting a lesion to the soft tissue pulley structures. The “pulley sign” is an extra-articular collection of contrast material anterior to the upper subscapularis muscle. A 2012 study established MRA criteria for diagnosing biceps pulley lesions. The findings on MRA included[rx]:

-

LHBT displacement relative to subscapularis tendon on oblique sagittal series; Up to 86% sensitive, 98% specific

-

LHBT tendinopathy on oblique sagittal image series; Up to 93% sensitive, 96% specific

-

Medial LHBT subluxation on axial image series; Up to 64% sensitive, 100% specific

-

Discontinuity of the SGHL; Up to 89% sensitive, 83% specific

Treatment Of Biceps Tendinopathy

Non-Pharmacological

- Rest – Rest, ice and heat are the initial steps to take to rehabilitate your muscles. Resting allows the muscle strain to heal, while ice reduces the inflammation and dulls your pain. Apply ice on a 15-minute on, 15-minute off schedule for the first day for grade 1 strains. Grade 1 strains are injuries that feel tight but do not produce pain or visible swelling of the shoulder area. Continue icing for several days for grade 2 and 3 strains. Strains of this severity will cause pain and hamper your mobility.

- Stretching and Strengthening – Stretching and strengthening your can help you recover from an injury and prevent future strains. Stretching can begin as soon as you are pain-free, and include the barbell stretch. Stand with your arms at your sides. Bring your arms up to shoulder height, keeping your elbows straight and arms out in front of you.

- Massage – Sports massage may be a part of your rehab program. A sports massage, administered by a certified professional, keeps your muscles loose and limber and warms the injured tissues. Grade 1 deltoid injuries may be massaged after the first two days of rest and icing; more severe strains or tears may require up to a week’s healing time before the massage is possible.

- Ultrasound – Grade 3 injuries can benefit from more advanced rehab techniques, including ultrasound and electrical stimulation. These types of treatments must be performed by certified professionals and may include your athletic trainer or physical therapist. Ultrasound treatments send sound waves into the deltoid muscle; electrical stimulation provides the injured tissues a low-grade electrical current. Both of these treatments can reduce pain and inflammation.

Medication

In Severe Condition of the Biceps Tendinopathy

- Antibiotic – Cefuroxime or Azithromycin, or Flucloxacillin or any other cephalosporin/quinolone antibiotic must be used to prevent infection or clotted blood remove to prevent furthers swelling and edema. Antibiotics and tetanus vaccination may be used if the bone breaks through the skin creating immunization.

- NSAIDs – Prescription-strength drugs that reduce both pain and inflammation. Pain medicines and anti-inflammatory drugs help to relieve pain and stiffness, allowing for increased mobility and exercise. There are many common over-the-counter medicines called non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). They include and Ketorolac, Aceclofenac, Naproxen, Etoricoxib.

- Corticosteroids – Also known as oral steroids, these medications reduce inflammation.

- Cortisone injections – First-line nonoperative management also includes the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs) medications in conjunction with PT modalities to rapidly reduce pain.

- Muscle Relaxants – These medications provide relief from associated muscle spasms or injury

- Neuropathic Agents – Drugs(pregabalin & gabapentin) that address neuropathic—or nerve-related—pain. This includes burning, numbness, and tingling.

- Opioids – Also known as narcotics, these medications are intense pain relievers that should only be used under a doctor’s careful supervision.

- Topical Medications – These prescription-strength creams, gels, ointments, patches, and sprays help relieve pain and inflammation through the skin.

- Calcium & vitamin D3 – To improve bone health and healing fracture. As a general rule, men and women age 50 and older should consume 1,200 milligrams of calcium a day, and 600 international units of vitamin D a day.

- Glucosamine & Diacerein, Chondroitin sulfate – can be used to tightening the loose tendon, cartilage, ligament, and cartilage, ligament regenerates cartilage or inhabits the further degeneration of cartilage, ligament.

- Dietary supplement -to remove general weakness & healing and improved health.

- Antidepressants – A drug that blocks pain messages from your brain and boosts the effects of endorphins (your body’s natural painkillers).

- Menthol – provides deep penetrating pain relief with a nice cooling sensation

- Vitamin B1, B6, B12– promotes normal nerve function

- Vitamin E – anti-inflammatory, enhances circulation, hydrates the skin

- Aloe vera – anti-inflammatory properties, soothes the skin

- Tea Tree – enhances the penetration of ingredients

- MSM – supports healthy connective tissues, anti-inflammatory

- Ilex Leaf Extract – increases circulation, skin conditioner

- Botulinum toxin injections – to her trapezius muscles, which considerably reduced pain and spasm. This clinical improvement lasted 3 months. Ongoing injections as required are planned.

Physical Therapy Management

Physical therapy has been commonly used for the treatment of tendinopathies: initially focusing on unloading followed by reloading the affected tendon.

- This may start with isometric training if the pain is the primary issue progressing into eccentric training and eventually concentric loading as with other forms of tendon rehab.

- Stretching and strengthening programs are a common component of most therapy programs. Therapists also use other modalities, including ultrasound, iontophoresis, deep transverse friction massage, low-level laser therapy, and hyperthermia; however evidence for these modalities has low quality.

- The physical therapist must consider both the patient’s subjective response to injury and the physiological mechanisms of tissue healing; both are essential in relation to a patient’s return to optimal performance.

As a preface to a discussion of the goals of treatment during injury rehabilitation, two points must be made:

- Healing tissue must not be overstressed and a very slow heavy loading program should be undertaken. During tissue healing, controlled therapeutic stress is necessary to optimize collagen matrix formation, but too much stress can damage new structures and slow the patient’s rehabilitation

- The patient must meet specific objectives to progress from one phase of healing to the next. These objectives may depend on ROM, strength, or activity. It is the responsibility of the physical therapist to establish these guidelines

Exercise therapy should include:

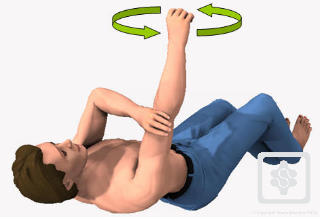

- Restoring a pain-free range of motion – Pain-free range can be achieved with such activities as PROM, Active-Assisted Range of Motion (AAROM), and mobilization via manual therapy

- Proper scapulothoracic rhythm.

- Painful activities such as abduction and overhead activities should be avoided in the early stages of recovery as it can exacerbate symptoms

- Strengthening program consisting of heavy slow loading should begin with emphasis on the scapular stabilizers, rotator cuff and biceps tendon

.gif)

E

E