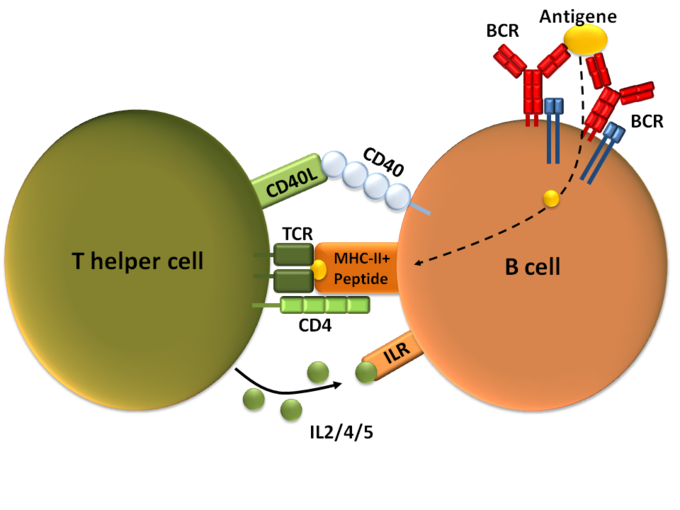

The humoral immune response is mediated by antibody molecules that are secreted by plasma cells. An antigen that binds to the B-cell antigen receptor signals B cells and is, at the same time, internalized and processed into peptides that activate armed helper. The extracellular spaces are protected by the humoral immune response, in which antibodies produced by B cells cause the destruction of extracellular microorganisms and prevent the spread of intracellular infections. The activation of B cells and their differentiation into antibody-secreting plasma cells is triggered by antigen and usually requires helper T cells. The term ‘helper T cell’ is often used to mean a cell from the TH2 class of CD4 T cells (see Chapter 8), but a subset of TH1 cells can also help in B-cell activation. In this case, we will therefore use the term helper T cell to mean any armed effector CD4 T cell that can activate a B cell. Helper T cells also control isotype switching and have a role in initiating somatic hypermutation of antibody variable V-region genes

Clonal Selection and B-Cell Differentiation

B cells mature in the bone marrow, where they undergo VDJ recombination to produce unique receptors that do not react to self-antigens.

Key Points

In the bone marrow, central tolerance of B cells is produced through negative selection. Immature B cells are tested for auto-reactivity before leaving the bone marrow. The immature B cells whose receptors (BCRs) bind too strongly to self-antigens will not be killed.

When the B cell receptor on the cell surface matches its cognate antigen in the body, the B cell proliferates and secretes a free form of those receptors ( antibodies ), with identical binding sites as on the original cell surface.

B cells that have not been exposed to an antigen, also known as naïve B cells, can be activated in a T cell-dependent or independent manner.

There are two types of T cell-independent activation: Type 1 T cell-independent (polyclonal) activation, and type 2 T cell-independent activation.

During clonal selection, random mutations during clonal expansion cause the production of B cells with an increased antibody-binding affinity for their antigens.

The clonal selection hypothesis may explain why secondary immune responses are so effective at preventing reinfection by the same pathogen.

Key Terms

- Clonal selection: The theory that lymphocytes bear antigen receptors before activation and that random mutations during clonal expansion cause the development of lymphocytes with high binding affinities for their antigens.

- humoral: Of or relating to the body fluids or humor.

- memory B cell: A B cell subtype formed following primary infection in which the cell recognizes a specific epitope.

B cells are lymphocytes that play a large role in the humoral immune response (as opposed to the cell-mediated immune response, which is governed by T cells). B cells primarily function to make antibodies against antigens, act as antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and eventually develop into memory B cells to provide long-term immunity. B cells undergo clonal selection and develop similarly to T cells with some notable differences.

B Cell Development

Immature B cells are produced in the bone marrow of most mammals. Their development occurs through several stages, each representing a change in the genome content at the antibody loci. An antibody is composed of two identical light (L) and two identical heavy (H) chains and the genes specifying them are found in the V (variable) region and C (constant) region. The heavy-chain V region has three segments, V, D and J. These segments recombine randomly in a process called VDJ recombination to produce a unique variable domain in the immunoglobulin of each individual B cell.

Similar rearrangements occur for the light-chain V region but with only two segments involved: V and J. When the B cell fails in any step of the maturation process, it will die by apoptosis, here called a clonal deletion. This is a form of positive selection. B cells are also tested for autoreactivity through negative selection. If these B cells have a high affinity for binding to self-antigens, they will die by clonal deletion or another pathway such as energy.

B Cell Activation

B cell activation refers to the differentiation and clonal expansion of B cells. When the B cell receptor on the cell surface matches its cognate antigen in the body, the B cell proliferates and secretes a free form of those receptors (antibodies) in the body, with binding sites identical to those on the original cell surface. However, B cell recognition of antigens is not the only element necessary for B cell activation. B cells that have not been exposed to an antigen, also known as naïve B cells, can be activated in a T cell-dependent or independent manner.

- T cell-dependent activation is the activation of B cells by type 2 helper T cells in the lymph nodes.

- T cell-independent activation occurs when antigens directly bind to B cells themselves, usually through cross-linking the antigen to the B cell receptor or receiving the antigen with a toll-like receptor.

T-dependent B cell activation: T cell-dependent B cell activation, showing a TH2-cell (left), B cell (right), and several interaction molecules.

B Cell Differentiation and Clonal Expansion

After activation, the B cell undergoes differentiation and clonal expansion, which usually involves migration to germinal centers if the activation takes place in a lymph node. B cell differentiation is the process by which B cells change into different types, such as plasma cells and plasmablasts. Clonal expansion is the process by which daughter cells arise from a parent cell. During B cell clonal expansion, many copies of that B cell are produced that share affinity with and specificity of the same antigen.

Clonal Selection

Clonal selection is a theory stating that B cells express antigen-specific receptors before antigens are ever encountered in the body. After B cell activation, the B cells clone themselves through clonal expansion, but during each cellular division, random mutations occur that gradually increase the binding affinity for B cell-produced antibodies to antigens.

For example, memory B cells that differentiate after an adaptive immune response are thought to undergo clonal selection so that antibodies produced by newer memory B cells have considerably higher binding affinities to their antigens. This theory may explain why secondary immune responses from memory cells are so effective that repeated infections by the same pathogen are stopped before symptoms even develop. Following the initial infection, random mutations during clonal selection could produce memory B cells that can more easily bind to antigens than can the original B cells.

Structure and Function of Antibodies

An antibody is a Y-shaped protein produced by B cells to identify and neutralize antigens in the body.

Key Points

An antibody, also known as an immunoglobulin, is a large Y-shaped protein produced by B- cells and used by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as bacteria and viruses.

Each tip of the “Y” of an antibody contains a paratope (a structure analogous to a lock) that is specific for one particular epitope (similarly analogous to a key) on an antigen, allowing these two structures to bind together with precision.

Though the general structure of antibodies is very similar, a small region at the tip of the protein is extremely variable, allowing millions of antibodies with different antigen-binding sites to exist. This region is known as the hypervariable region.

Five isotypes of antibodies are found in different locations and perform different specific functions.

The base of the Y plays a role in modulating immune cell activity. This region is called the Fc region, and phagocytes may bind to it to initiate phagocytosis.

Antibodies that bind to surface antigens on a bacterium attract the first component of the complement cascade with their Fc region and initiate activation of the classical complement system.

Key Terms

- epitope: Part of a biomolecule (such as a protein) that is the target of an immune response.

- paratope: Part of the molecule of an antibody that binds to an antigen.

- isotype: A marker corresponding to an antigen found in all members of a subclass of a specific class of immunoglobulins.

An antibody (formally called immunoglobulin) is a large Y-shaped glycoprotein produced by B-cells and used by the immune system to identify and neutralize pathogens. Antibodies are produced by B cells, and are either secreted into circulation or remain expressed on the surface of the B cell.

Structure of Antibodies

The antibody recognizes a unique part of an antigen (foreign object). Each tip of the “Y” of an antibody contains a paratope (a structure analogous to a lock) that is specific for one particular epitope (similarly analogous to a key) on an antigen, allowing these two structures to bind together with precision. Using this binding mechanism, an antibody can neutralize its target directly or tag it for attack by other parts of the immune system.

Antibody: Each antibody binds to a specific antigen, an interaction similar to a lock and key.

Antibodies are glycoproteins belonging to the immunoglobulin superfamily, typically made of basic structural units each with two large heavy chains and two small light chains. Most antibodies exist as a monomer, in which they have a single “Y” shaped sub-unit, but some antibodies can exist as dimers (two subunits) or pentamers (five subunits). The paratope is considered a hypervariable region and has the same specificity and antigen-binding affinity as the B cell receptor of the B cell that created the antibody. In some isotypes, the tail end of the antibody is called the constant region and faces away from the “Y-shaped” paratope ends, functioning as an Fc tail to which phagocytes can bind.

Isotypes

Five different isotypes of antibodies each perform different functions and are generally found in different parts of the body.

- IgA: A dimer secreted into mucosal surfaces, such as the gut, respiratory tract, and urogenital tract, that prevents mucosal invasion into the body by pathogens. It is resistant to the proteolytic enzymes found in the gastrointestinal mucosae.

- IgD: Functions mainly as an antigen receptor on B cells that have not been exposed to antigens. It has been shown to activate basophils and mast cells to produce antimicrobial factors.

- IgE: Found in circulation and binds to allergens, triggering histamine release from mast cells and basophils. Also protects against parasitic worms.

- IgG: Has four different forms and provides the majority of antibody-based immunity against invading pathogens as the best opsonin of any type of antibody. This is because it expresses a tail for Fc receptors on phagocytes to bind to, which activates phagocytosis. It is the only antibody capable of crossing the placenta to give passive immunity to fetus and can activate the classical complement system.

- IgM: Expressed on the surface of B cells (monomer) and in a secreted pentamer with very high avidity. Eliminates pathogens in the early stages of B cell-mediated (humoral) immunity before there is sufficient IgG. Like IgG, it can also activate the classical complement system.

Function of Antibodies

Circulating antibodies are produced by clonal B cells that specifically respond to only one antigen. Antibodies contribute to immunity in three ways: preventing pathogens from entering or damaging cells by binding to them (neutralization); stimulating the removal of pathogens by macrophages and other cells by coating the pathogen (opsonization); and triggering the destruction of pathogens by stimulating other immune responses such as the complement pathway. The complement system starts a long cascade of protein productions that either opsonize a pathogen for phagocytosis or lyse it directly by forming a membrane attack complex. During opsonization, the antibody expresses the tail for an Fc receptor on a macrophage, neutrophil, or natural killer cell. The immune cell will then bind to the antibody’s Fc tail instead of the pathogen itself, which speeds up the process of finding pathogens to phagocytize. Additionally, because antibodies have two or more paratopes, they can sometimes link pathogens together, making phagocytosis more efficient.

Role of the Complement System in Immunity

The complement system is the ability of antibodies and phagocytic cells to remove pathogens from an organism.

Key Points

The complement system helps antibodies and phagocytic cells clear pathogens from an organism.

The complement system consists of a number of small proteins produced by the acute phase reaction in the liver during inflammation.

The complement system might play a role in diseases with an immune component and those of the central nervous system. Complement protein deficiency is a form of primary immunodeficiency.

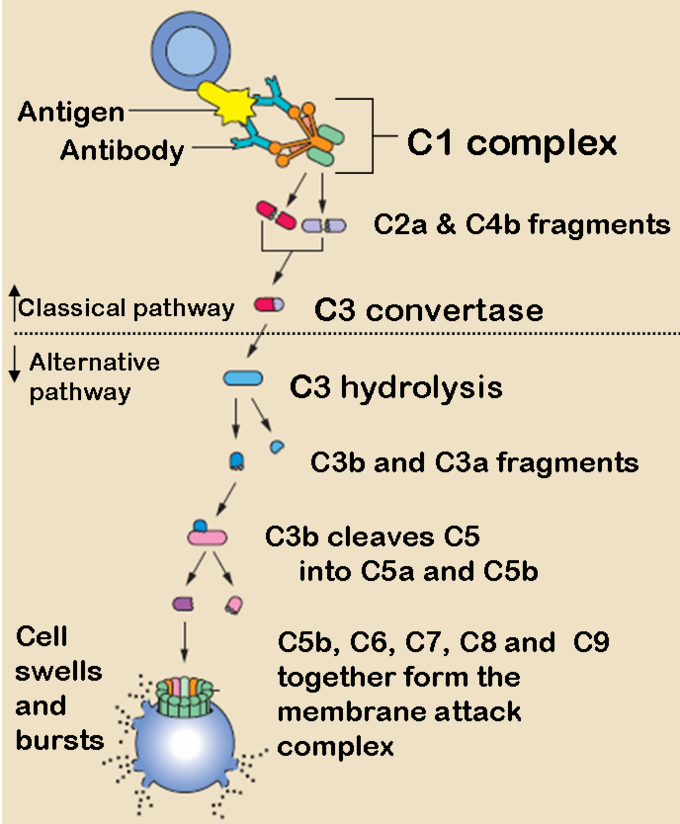

The classical complement pathway starts with antibody binding, which causes a cascade reaction of complement proteins that gradually form a membrane attack complex.

The alternative complement pathway is usually stimulated by pathogen antigens or toxins rather than antibodies and cleaves C3 until there is enough to continue the steps of the classical complement pathway from the C5 convertase step.

The lectin pathway is homologous to the classical pathway, but with the opsonin, mannose-binding lectin (MBL), and ficolins, instead of C1 from the antibody. This pathway uses proteases on the MBL to form C3 convertase, which continues the steps of the classical complement pathway from the C3 convertase step.

The complement system is regulated by complement control proteins, such as the decay-accelerating pathway, which prevent complement proteins from forming MAC on the body’s cells.

Key Terms

- C5a: A complementing protein that is an acute phase, inflammatory mediator, causing vasodilation and neutrophil chemotaxis.

- membrane attack complex: The final complex of all complement system pathways that lyses the pathogen. It is composed of C5b, C6, C7, C8, and C9.

- mannan-binding-lectin: A protein that binds to carbohydrates on pathogens to activate the lectin complement pathway.

The complement system or “complements” the ability of antibodies and phagocytic cells to clear pathogens from an organism. The complement system consists of a number of small proteins found in the blood, generally synthesized by the liver as a part of the acute phase reaction during systemic inflammation (from TNF-alpha release). When stimulated by one of several triggers, proteases in the system cleave specific proteins to release cytokines and initiate an amplifying cascade of further cleavages. The end result of this activation cascade is massive amplification of the response and activation of the cell-killing membrane attack complex (also called MAC). There are three different pathways by which the complement system may occur.

Classical Complement Pathway

The classical complement pathway is the main pathway by which the complement system occurs. It is comprised of a cascade of many steps with complement proteins cleaving one another in sequential order:

- The antibody binds to an antigen on the surface of a pathogen, activating the C1 complement protein.

- C1 acts as a protease and cleaves C2 and C4 to form C4b2b.

- C42b converts C3 into C3a and C3b, which forms a C5 convertase.

- C5 convertase cleaves C5 into C5a and C5b.

- C5b forms a complex with C6, C7, and then C8, and C9, which becomes the membrane attack complex that lyses the pathogen.

Note that C5a has a number of other functions in the immune system, such as causing vasodilation during inflammation and stimulating neutrophil chemotaxis. Additionally, the body’s cells express a glycoprotein called decay accelerating factor, which decays C3 and C5 convertase on the body’s cells. This factor prevents membrane attack complexes from forming on the body’s cells under normal conditions.

The Classical and Alternative Complement Pathways: The classical and alternative complement pathways start off differently, but end in the same cascade of complement proteins that combine to form a membrane attack complex.

The Alternative Complement Pathway

The alternative pathway may be a leftover evolutionary precursor to the classical pathway. Unlike the classical pathway, the alternative pathway is generally activated by microbial inflammatory mediators instead of antibodies. For example, lipopolysaccharide, the toxin of gram-negative bacteria, may activate this pathway. The steps for the alternative pathway are:

- The pathogenic antigen (such as LPS) activates C3 so it creates a C3B complex

- Factor D cleaves the C3B complex so that C3bBb is created.

- C3bBb is a C3 convertase, which converts more C3 into C3a and C3b.

- Similar to the classical pathway, C3b forms a C42b complex, and the rest of the steps are essentially the same as the classical pathway, ending with C5b forming a membrane attack complex with C6, C7, C8, and C9.

Lectin Pathway

The lectin pathway is not caused by antibody binding, but by a carbohydrate -binding-protein called mannan-binding-lectin (MBL). It is an acute-phase reactant produced in the liver and binds to the carbohydrates on the surfaces of many pathogens. The steps for the lectin pathway are:

- MBL binds to the carbohydrates on a pathogen.

- Proteases bound on the other side of the MBL cleaves C4 into C4a and C4b.

- C4b creates C3 convertase, and the rest of the steps happen identically to the classical pathway from the C3 convertase step.

Problems with the Complement System

The complement system might play a role in diseases with an immune component, such as Barraquer-Simons Syndrome, asthma, lupus erythematosus, glomerulonephritis, various forms of arthritis, autoimmune heart disease, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, ischemia-reperfusion injuries, and rejection of transplanted organs. The complement system is also becoming increasingly implicated in diseases of the central nervous system such as Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative conditions such as spinal cord injuries. Additionally, deficiencies in complement proteins produced in the liver can lead to a form of primary (congenital) immunodeficiency, in which the body is more susceptible to disease, particularly autoimmune diseases and severe bacterial infections.

Immunological Memory

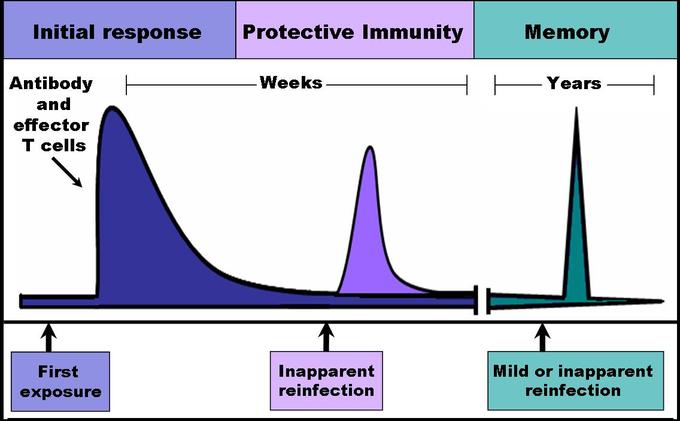

Immunological memory refers to the ability of B and T cells to produce long-lived memory cells that defend against specific pathogens.

Key Points

When B and T cells begin to replicate, some offspring will become long-lived memory cells.

Memory cells remember all specific pathogens encountered during the animal’s lifetime and can thus call forth a strong response if the pathogen ever invades the body again.

Passive immunity comes from IgG antibodies given through the mother during fetal development and through breast milk. This memory is short-term but protects the infant until its own adaptive immune system is functional.

During a secondary immune response, memory B and T cells work to rapidly eliminate the pathogen, preventing reinfection by the same pathogen.

During a vaccination, the antigen of a pathogen is introduced into the body through a weakened form of the pathogen that cannot cause an infection. This stimulates the immune system to develop specific immunity against that pathogen without actually causing the disease that the pathogen brings.

Vaccines do not exist for every pathogen due to frequent strain mutations and challenges in producing an immunization strong enough to work, but not strong enough to cause an infection.

Key Terms

- secondary immune response: The act of exposure to the same pathogen after the initial immune response. Memory B and T cells work to rapidly eliminate the pathogen to prevent reinfection.

- vaccination: Inoculation with the weakened form of a pathogen to protect against a particular disease or strain of disease by stimulating the development of immunological memory against that pathogen.

When B and T cells begin to replicate during an adaptive immune response, some offspring become long-lived memory cells. These memory cells remember all specific pathogens encountered during the animal’s lifetime and can thus call forth a stronger response, called the secondary immune response, if the pathogen ever invades the body again. The adaptive immune system is so-named because it is a result of an adaptation to an infection. Immunological memory can either exist in active long-term memory or passive short-term memory.

Immune response: When B and T cells begin to replicate, some of the offspring that they produce will end up becoming long-lived memory cells. These memory cells will remember all specific pathogens encountered during the animal’s lifetime and can thus call forth a strong response if the pathogen ever invades the body again.

Passive Memory

Newborn infants are particularly vulnerable to infections since they have no prior exposure to pathogens. Thus, the mother protects the infant through several layers of passive protection. During pregnancy, IgG, a certain isotype of antibody, is transported to the baby from the mother through the placenta, so even babies have high levels of antibodies with similar antigen specificities as the mother. Even breast milk contains antibodies that are transferred to the infant’s gastrointestinal tract and protect against bacterial infections until the baby is capable of making its own antibodies. Since the fetus isn’t making any memory cells or antibodies, this is called passive immunity. Passive immunity is short-lived, ranging from a couple days to a couple months.

As the infant matures, their thymus and bone marrow work to raise a stock of mature lymphocytes that form the foundation for the infant’s personal adaptive immune system. Because the passive memory comes from antibodies instead of B cells themselves, infants do not inherit long-term immunological memory from the mother. Even if the infant receives antibodies specific to certain diseases from its mother, the infant wouldn’t be able to bolster a long-term memory that would direct antigen exposure and presentation.

Active Memory and Immunization

Following an infection, long-term active memory is acquired by activation of B and T cells. Memory cells derive from their parent B and T cells, and undergo clonal selection following infection, which increases antigen-binding affinity. Following reinfection, the secondary immune response typically eliminates the pathogen before symptoms of an infection can occur. During the secondary immune response, memory T cells rapidly proliferate into active helper and cytotoxic T cells specific to that antigen, while memory B cells rapidly produce antibodies to neutralize the pathogen. Long-term active memory consists of rapid response and form permanent immunological memory so long as those memory cells survive.

Vaccinations take advantage of memory lymphocyte development by artificially-generating active immunity, a process called immunization. During a vaccination, the antigen of a pathogen is introduced into the body and stimulates the immune system to develop a specific immunity against that pathogen. It doesn’t cause the disease that the pathogen brings because the vaccine uses an attenuated form of the pathogen that contains the same antigen but doesn’t have the capacity for replication. This deliberate introduction of the pathogen is successful since it exploits the immune system’s natural specificity and inducibility. Vaccination is an extremely effective manipulation of the immune system that helps fight diseases. Over the course of vaccine development, they have saved countless lives, and diseases like rubella and polio are not the widespread causes of disability they once were.

Despite the effectiveness of vaccines, methods do not yet exist to develop vaccines for every pathogen. Many pathogens undergo mutations that change the expression of their antigens, making immunization attempts fruitless for diseases like the common cold or norovirus. Many parasitic pathogens, such as the plasmodium protist that causes malaria, haven’t successfully been vaccinated against because it is challenging to develop a vaccine that is strong enough to stimulate an immune response (sufficient immunogenicity) without causing a live infection.

Major Histocompatibility Complex Antigens (Self-Antigens)humoral immune response

The major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a cell surface molecule that regulates interactions between white blood cells and other cells.

Key Points

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a cell-surface molecule that mediates interactions between white blood cells and other leukocytes or cells.

The MHC is divided into class I, class II, and class III subgroups, all encoded by the same gene.

MHC antigen presentation gains its diversity from the high degree of polymorphism of the MHC protein itself.

Differing HLA between members of the same species is the main reason why transplanted organs are rejected by the organ recipient.

Key Terms

- human leukocyte antigen (HLA): The name of the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) in humans.

Major histocompatibility complex (MHC) is a cell-surface molecule encoded by a large gene family in all vertebrates. MHC molecules mediate the interactions of leukocytes with other leukocytes or body cells. MHC determines the compatibility of donors for organ transplant as well as one’s susceptibility to an autoimmune disease via cross-reacting immunization. In humans, MHC is also called human leukocyte antigen (HLA), because MHC can often act as an antigen for human leukocytes.

Types of MHC

MHC is a polymorphic protein attached to the surface of cells. Three different classes of MHC differ in structure and function in the immune system but are all encoded by the same set of gene sequences.

- MHC I is presented on all cells of the body. It contains an epitope that forms the structural binding site for an antigen. MHC I interacts with natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic T cells to signal whether a cell is a self or non-self and whether it contains an antigen-specific to that T cell.

- MHC II is presented mainly on macrophages, dendritic cells, and helper T cells, which are all involved in antigen presentation. It has a longer helical region than MHC I, which allows it to bind to CD4 (helper T cells) during antigen presentation.

- MHC III is a secreted enzyme that is neither membrane-bound nor involved in antigen presentation like MHC I and II. It is merely included as an MHC protein because it is encoded by the same set of genes. It is involved in the production of complement proteins and inflammatory cytokines.

During antigen processing prior to presentation, protein peptides from pathogens and MHC (I or II) travel through the cytoplasm and then to the cell membrane surface. A complex series of vesicles enables MHC transport from the cell, and the endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi bodies facilitate this transport during antigen processing. After processing, the MHC can present the peptide antigen bound to it to naive T cells.

MHC Class I processing: MHC class I pathway: proteins in the cytosol are degraded by the proteasome, liberating peptides internalized by the TAP channel in the endoplasmic reticulum, there associating with MHC-I molecules freshly synthesized. MHC-I/peptide complexes enter the Golgi apparatus, are glycosylated, enter secretory vesicles, fuse with the cell membrane, and externalize on the cell membrane interacting with T lymphocytes.

MHC Class I: MHC class I protein molecule.

MHC Class II: MHC class II protein molecule.

HLA and Organ Rejection

Organ transplantation is a complex procedure that can potentially cure many chronic diseases and acute injuries. However, surgically replaced organs are often rejected by the body’s immune system. MHC is also called human leukocyte antigen (HLA) and varies considerably among different members of the same species. If the T and B cells of the body recognize the HLA of the graft as foreign, they will attack the organ graft. The damage in organ rejection can be acute or chronic, cell-mediated or antibody-mediated, and often involves diffuse damage of the graft that causes necrosis and infarction ( tissue death from lack of oxygen) to the graft tissue by attacking its vascular components.

In nearly all cases, immunosuppressive chemotherapy is a requirement for successful organ transplantation. These drugs can stop acute organ rejection after the procedure, but will not stop chronic organ rejection, in which gradual vascular lesions and endothelial thickening slowly kill the graft. If an organ donor has HLA similar to that of the recipient, the risk of organ rejection is reduced. However, this isn’t feasible for heart, liver, or lung transplants because there generally isn’t enough time in these cases to find a matching organ donor.

References