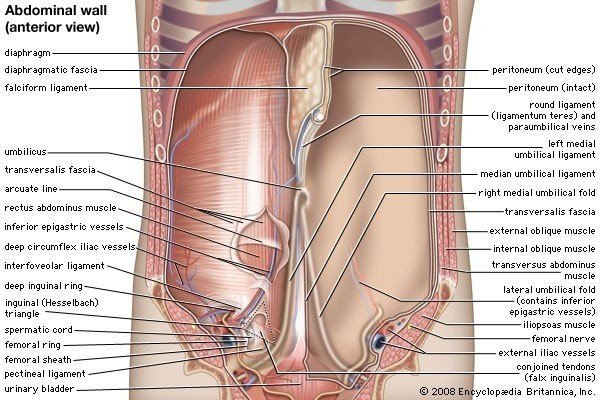

What are the four abdominal muscles?/Abdominal Muscles of the anterolateral wall consist of five, large, paired muscles. Beginning laterally and most superficially, the external oblique muscles are the first muscular layer originating from the fifth to twelfth ribs and inserting at the linea alba, pubic tubercle, and anterior half of iliac crest. It is responsible for compressing the abdominal viscera as well as the movement of the trunk by flexing and rotating. The fibers of the external oblique run anteromedially. The internal oblique in contrast to the external oblique runs superomedially from the thoracolumbar fascia, anterior two-thirds or iliac crest to the inferior borders of the tenth-twelfth ribs, linea alba, and pectin pubis via the conjoint tendon.

Abdominal Muscle is the structure encasing the abdominal organs. It is the muscular layer of tissues that extends from the thoracic and lumbar spine to the anterior abdominal cavity. The boundary between the lateral and anterior wall is not defined, and therefore, the name anterolateral is used to describe the wall as it wraps from posterior to anterior. It serves to protect the internal organs of the digestive system as well as the alimentary tract. Multiple layers of fascia, muscle, nerves, and vasculature make up the anterolateral wall. The anterolateral wall demonstrates a vast degree of function as well as compliance for what the gastrointestinal tract needs. Throughout this article, we will explore the anatomy of the anterolateral abdominal wall, its function, as well as its embryologic origins.[rx]

Abdominal Muscles

The five muscles in the abdominal wall are divided into two groups

- (1) two vertical muscles situated near the midline of the body and

- (2) three flat muscles located laterally and stacked on top of each other. The three flat muscles include the external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis.

- (3)The flat muscles flex and rotate the trunk. Because the fibers of these muscles criss-cross and interlink with each other, they also strengthen the abdominal wall and reduce the risk of herniation.[rx][rx][rx]

Flat Muscles

-

External Oblique – the most superficial and also the largest flat muscle of the abdominal wall. It runs in an inferior-medial direction and at the midline, its fibers form an aponeurosis and in the midline merge with the linea alba. This fibrous structure extends from the xiphoid process to the pubic symphysis.

-

Internal Oblique – located deeper to the external oblique and is much thinner and smaller. Its fibers run superomedial and near the midline form aponeurosis which contributes to the linea alba.

-

Transversus Abdominis – the deepest of the flat muscles and its fibers run transversely. It also continues to the linea alba in the midline. Just beneath the transversus abdominis muscle is the transversal fascia.

Vertical Muscles

-

Rectus Abdominis – long paired vertical muscle located on either side of the midline. It is divided into two segments by the linea alba. The lateral border of the muscle is called the linea semilunaris. At several locations, the muscle is intersected by fibrous intersections which give rise to the “six-pack” seen in athletes. The rectus abdominis compresses the abdominal viscera, prevents herniation, and stabilizes the pelvis during ambulation.

-

Pyramidalis – vertical muscle shaped like a triangle. It is located superficial to the rectus abdominis and located at the base of the pubic bone. The apex of the triangle attaches to the linea alba.

Rectus Sheath

The Rectus Sheath is an aponeurosis formed by the five muscles of the abdomen. It has an anterior and posterior wall for most of its length. The anterior wall is formed by the aponeurosis of the external oblique and half of the internal oblique. The posterior wall is formed by the aponeurosis of the half of the internal oblique and transversus abdominis.

This list may not reflect recent changes.

- Abdominal external oblique muscle

- Abdominal internal oblique muscle

- The aponeurosis of the abdominal external oblique muscle

- Bulbospongiosus muscle

- Coccygeus muscle

- Corrugator cutis ani muscle

- Cremaster muscle

- Detrusor muscle

- Erector spinal muscles

- External intercostal muscles

- Iliocostalis

- Innermost intercostal muscle

- Intercostal muscle

- Internal intercostal muscles

- Interspinal muscles

- Intertransversarii

- Ischiocavernosus muscle

- Levator ani

- Lavatories costarum muscles

- Longissimus

- Multifidus muscle

- Template: Muscles of the abdomen

- Pectoral muscles

- Pelvic floor

- pubovaginal muscle

- Pyramidalis muscle

- Quadratus lumborum muscle

- Rectococcygeal muscle

- Rectus abdominis muscle

- Rectus sheath

- Rhomboid muscles

- Rotatores muscles

- Sebileau’s muscle

- Semispinalis muscles

- Serratus

- Serratus anterior muscle

- Serratus posterior inferior muscle

- Serratus posterior superior muscle

- Spinalis

- Splenius capitis muscle

- Splenius cervicis muscle

- Splenius muscles

- Subcostalis muscle

- Thoracic diaphragm

- Transverse abdominal muscle

- Transversospinales

- Transversus thoracis muscle

- Urogenital hiatus

Blood Supply/Abdominal Muscles

Arterial Supply

The arterial supply to the abdominal wall is derived from the following:

Six Most Inferior Intercostal Arteries and Lumbar Arteries

-

Courses from lateral to medial in-between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles along with the intercostal, iliohypogastric and ilioinguinal nerves. The branches pierce the lateral border of the rectus sheath and freely communicate with the epigastric arteries.

Superior Epigastric Arteries

-

A terminal branch of the internal mammary, also known as the internal thoracic, artery bilaterally. Descends within the rectus sheath (posterior to the rectus muscle but anterior to the posterior rectus sheath) to form an anastomosis with the inferior epigastric artery.

Inferior Epigastric Arteries

-

A branch of the external iliac artery just before it crosses the inguinal ligament. It courses superiorly in the pre-peritoneal space (space between the transversalis fascia and parietal peritoneum) to meet the superior epigastric vessels.

Deep Circumflex Iliac Arteries

-

Arises from the external iliac artery laterally just distal to the inferior epigastric artery branching; contributes blood to the abdominal wall via an ascending branch

Nerves of Abdominal Muscles

The autonomic nerves (sympathetic and parasympathetic systems) supply the visceral peritoneum, whereas the parietal peritoneum has spinal nerves deriving the somatic innervation.[rx] The visceral peritoneum senses dull, poorly localized pain when stretched out or distended and is associated with diaphoresis and nausea.[rx] Thus, a patient may perceive a vague abdominal pain in a general region. However, when the parietal peritoneum is involved, patients experience a sharp, localized type of pain in a specific area.

Abdomen

-

Left and right vagus nerve – parasympathetic innervation

-

Gastric nerves

-

Celiac plexus from spinal cord segments T6 to T9

-

Subcostal nerve

-

Iliohypogastric

Pelvis

-

Pelvic splanchnic

-

Obturator

-

Ilioinguinal

-

Genitofemoral

-

Superior gluteal

-

Inferior gluteal

-

Lateral femoral cutaneous nerve

-

Sacral plexus from L4 through S4: sciatic nerve, pudendal nerve, gluteal nerves, nerve to obturator internus, nerve to piriformis

References