Urine Elimination/Urine transport means the transport of water, ions, and secreted molecules that leave the collecting duct of the many nephrons of the kidney and flow into the ureters. The ureters are two tubes that drain urine from the kidneys to the bladder. Each ureter is a muscular tube that drains into the bladder.

Composition of Urine

The two kidneys filter your entire blood volume many times each day to remove wastes as urine. Characteristics of urine can be variable depending on water intake and losses, nutrient intake, and other factors described in this chapter, though cells, proteins, and blood are not normally found in the urine. Some of the characteristics such as color and odor are rough descriptors of your state of hydration. For example, if you exercise or work outside, and sweat a great deal, your urine will turn darker and produce a slight odor. Alternatively, a well-hydrated person will have light or clear colored urine with little odor.

| Normal Urine Characteristics (Table 25.1) | |

|---|---|

| Characteristic | Normal values |

| Color | Pale yellow to deep amber |

| Odor | Odorless |

| Volume | 750–2000 mL/24 hour |

| pH | 4.5–8.0 |

| Specific gravity | 1.003–1.032 |

| Osmolarity | 40–1350 mOsmol/kg |

| Urobilinogen | 0.2–1.0 mg/100 mL |

| White blood cells | 0–2 HPF (per high-power field of microscope) |

| Leukocyte esterase | None |

| Protein | None or trace |

| Bilirubin | <0.3 mg/100 mL |

| Ketones | None |

| Nitrites | None |

| Blood | None |

| Glucose | None |

Overview of Urine Transport, Storage, and Elimination

The urinary organs include the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra.

Key Points

Urine collects from the nephrons and flows into the ureters.

The ureters use smooth muscle contractions to facilitate the flow of urine.

The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular, and elastic organ that stores urine.

Urine exits the bladder and the body through the urethra.

The kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra make up the urinary tract, the pathway through which urine flows and is eliminated from the body.

Key Terms

- ureter: These are two long, narrow ducts that carry urine from the kidneys to the urinary bladder.

- urinary bladder: An elastic, muscular sac situated in the pelvic cavity, into which urine from the kidneys is stored prior to disposal by urination. Urine enters the bladder via the ureters and exits via the urethra.

The Urinary System

Urinary tract: The transport and removal of urine from the body follows the urinary tract.

The organs, tubes, muscles, and nerves that work together to create, store, and carry urine are referred to as the urinary system, which is another name for the renal system. The renal system filters the plasma of blood and regulates blood volume by excreting excess water in the form of urine. Urine transport follows a path through the kidneys, ureters, bladder, and urethra, which are collectively known as the urinary tract.

Urine Transport

Urine is essentially water, ions, and secreted molecules that leave the collecting duct of the many nephrons of the kidney and flow into the ureters. The ureters are two tubes that drain urine from the kidneys to the bladder.

Each ureter is a muscular tube that drains into the bladder. Smooth muscle contractions in the walls of the ureters, over time, send the urine in small spurts into the bladder, the organ where urine is stored before it can be eliminated.

Urine Storage

The bladder is a hollow muscular organ shaped like a balloon. It sits in the pelvis and is held in place by ligaments attached to other organs and the pelvic bones. The bladder stores urine until enough of it accumulates for removal from the body. It swells into a round shape when it is full and gets smaller when empty.

If the urinary system is healthy, the bladder can hold up to 16 ounces (2 cups) of urine comfortably for 2 to 5 hours. Circular muscles called sphincters help keep urine from leaking. The sphincter muscles close tightly, like a rubber band, around the opening of the bladder into the urethra, the tube that allows urine to pass outside the body.

Urine Elimination

Nerves in the bladder are stimulated as the bladder fills with urine and becomes larger, which in turn stimulates the need to urinate. When you urinate, the brain signals the bladder muscles to tighten, squeezing urine out of the bladder.

At the same time, the brain signals the sphincter muscles to relax. As these muscles relax, urine exits the bladder through the urethra, and leaves the body through an opening in the genital region that contains the urethra. When all the signals occur in the correct order, normal urination occurs, removing urine from the body.

Ureters

The ureters are two tubes that drain urine from each of the kidneys into the bladder.

Key Points

The ureter contains transitional epithelium and an additional smooth muscle layer in the more distal one-third to assist with peristalsis.

The ureters are usually 25–30 cm (10–12 in) long and 3–4 mm in diameter.

Muscles in the walls of the ureters send the urine in small spurts into the bladder.

Kidney stones are a common disease of the ureter, in which a stone made of minerals obstructs the ureter.

The ureter has a few points of constriction where kidney stones are more commonly found.

Key Terms

- transitional epithelial tissues: Epithelial tissues that can change between columnar and squamous forms that are found in the ureters and the cervix.

- peristalsis: The rhythmic, wave-like contraction of smooth muscle tissue that can propel substances through the many muscular tubes of the body.

The ureters are tubes made of smooth muscle fibers that propel urine from the kidneys to the urinary bladder. In the adult, the ureters are usually 25–30 cm (10–12 in) long and 3–4 mm in diameter. The ureter is one of the essential organs of urinary tract that controls urine transport.

Ureter Structure and Function

The ureters are two tubes that are made out of smooth muscle and transitional epithelial tissues, which are a type of epithelial tissue that may either be columnar or squamous. Each kidney has its own ureter through which urine drains into.

Human urinary system: 1) Human urinary system. 2) Kidney. 3) Renal pelvis. 4) Ureter. 5) Urinary bladder. 6) Urethra (left side with frontal section). 7) Adrenal gland vessels. 8) Renal artery and vein. 9) Inferior vena cava. 10) Abdominal aorta. 11) Common iliac artery and vein with transparency. 12) Liver. 13) Large intestine. 14) Pelvis.

The ureters are long tubes that have a few points of constriction, where obstructions are more common. The ureters receive a blood supply from a few different major arteries including the renal and iliac artery derivatives and have a relatively dense nerve supply as well.

Muscles in the walls of the ureters send the urine in small spurts into the bladder, in a process called peristalsis. After the urine enters the bladder from the ureters, small folds in the bladder mucosa act like valves to prevent the backward flow of the urine; these are called the ureteral valves. The ureteral valves function similarly to the semilunar valves in the veins of the body, but are structurally different, consisting of transverse mucosal epithelial folds.

Ureter Pathology

Kidney stones and cancer are common diseases of the ureter. A kidney stone can move from the kidney and become lodged inside the ureter, which can block the flow of urine, as well as cause a sharp cramp in the back, side, or lower abdomen. The affected kidney could then develop hydronephrosis, should a part of the kidney become swollen due to the blocked flow of urine.

Kidney stones are very common and are usually clumps of aggregated minerals that are most often found at the constriction points in the ureter. Ureter cancer is often due to a malignant transformation of the transitional epithelial tissue, which is more vulnerable to developing cancer cells compared to other tissues.

Urinary Bladder

The urinary bladder is a hollow, muscular, and distensible or elastic organ that sits on the pelvic floor.

Key Points

The bladder is made of transitional epithelium and has a trigone.

A normal bladder empties completely upon a complete discharge, otherwise, it is a sign that its elasticity is compromised.

When the bladder becomes half full, stretch receptors send nerve impulses to the spinal cord, which then sends a reflex nerve impulse back to the sphincter (a muscular valve) at the neck of the bladder, causing it to relax and allow the flow of urine into the urethra.

The internal urethral sphincter is involuntary and the external sphincter is voluntary.

The bladder plays a minor role in temperature regulation.

The bladder has both mechanical and sensory innervation through the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous systems.

Key Terms

- trigone: A triangle-shaped part of an organ, such as the bottom of the bladder.

- urine: A liquid excrement consisting of water, salts, and urea that is made in the kidneys then released through the urethra.

- reflex: An automatic response to a simple stimulus that does not require mental processing.

The Urinary Bladder

The urinary bladder is a urine storage organ that is a part of the urinary tract. The bladder is a hollow, muscular, and elastic organ that sits on the pelvic floor. The bladder expands and fills with urine before it is discharged into the urethra during urination.

Bladder Anatomy

The bladder is a hollow, sac-like organ made of transitional epithelium, similar to the ureter that feeds into it. The ureters enter the bladder diagonally from its dorsolateral floor in

an area called the trigone, which is a triangle-shaped anatomical region. The urethra exits at the

lowest point of the triangle of the trigone.

There are two sphincters or muscular valves, that separates the bladder from the urethra. The sphincters must open before the urine can flow into the urethra. The internal sphincter is under involuntary control and the external sphincter is under voluntary control.

Bladder Physiology

The urinary bladder: The urinary bladder is composed of several layers of tissue that facilitate urine storage and expulsion. The associated structures of the urinary and male reproductive tract are labeled.

When the bladder fills with urine stretch receptors send nerve impulses to the spinal cord, which then sends a reflex nerve impulse back to the internal sphincter valve at the neck of the bladder that causes it to relax and allow the flow of urine into the urethra. The internal urethral sphincter is involuntary and controlled by the autonomic nerves.

The bladder has a minor temperature regulation function since some heat may leave the body in the form of urine. A normal bladder empties completely upon a complete discharge, otherwise, it is a sign that its elasticity is compromised; when it becomes completely void of fluid, it may cause a chilling sensation due to the rapid change of body temperature.

The urinary bladder usually holds 300–350 ml of urine. As urine accumulates, the walls of the bladder thin as it stretches, allowing the bladder to store larger amounts of urine without a significant rise in the internal pressure of the bladder.

The bladder receives motor innervation from both sympathetic fibers, most of which arise from the hypogastric plexuses and nerves, and parasympathetic fibers, which come from the pelvic splanchnic nerves and the inferior hypogastric plexus. Sensation from the bladder is transmitted to the central nervous system (CNS) via general visceral afferent fibers.

Urethra

The urethra is a muscular tube that connects the bladder with the outside of the body and removes urine from the body.

Key Points

The external urethral sphincter is a striated muscle that allows voluntary control over urination.

Since the urethra is much shorter in females, they are much more susceptible to bacterial infections or urinary tract infections.

The urethra has smooth muscle tissue, erectile tissue, and mucous membrane tissue. In males, the urethra travels through the penis and carries semen as well as urine.

Semen is carried into the urethra through the vas deferens.

Key Terms

- vagina: A fibromuscular tubular tract that is the female sex organ and has two main functions: sexual intercourse and childbirth.

- penis: The male sexual organ for copulation and urination; also the tubular portion of the male genitalia (excluding the scrotum).

The Urethra

The urethra is a tube that connects the urinary bladder to the genitals for the removal of fluids from the body. The external urethral sphincter is a striated muscle that allows voluntary control over urination by controlling the flow of urine from the bladder into the urethra.

The Female Urethra

Female urethra: A depiction of a female urethra.

In females, the urethra is shorter relative to males and emerges above the vaginal opening. Its lining is composed primarily of non-keratinized stratified squamous epithelium that becomes transitional near the bladder. The urethra consists of three layers of tissues:

- The muscular layer is a continuation of the smooth muscle of the bladder.

- The erectile urethral tissue is a specialized tissue that may become engorged with blood during sexual arousal.

- The mucous urethral tissue is mucous membranes that line the interior of the urethra. The mucous membranes are especially important for protecting the urethral tissues from the corrosive effects of urine.

The urethral sphincter separates the bladder from the urethra. Somatic (conscious) innervation of the external urethral sphincter is supplied by the pudendal nerve, which allows the sphincter to open and close. As the urethra is shorter in females relative to males, they are more vulnerable to bacterial urinary tract infections.

The Male Urethra

In males, the urethra travels through the penis and carries semen as well as urine. Semen does not flow through the bladder or the rest of the urinary tract, instead, it is a fluid made of sperm cells and other fluids that passes through a few different glands from the testes to the urethra through the vas deferens. Aside from semen, and the male urethra’s greater length, it is structurally similar to the female urethra.

Male urethra: A detailed view of the male urethra.

Micturition and the Micturition Reflex

Micturition is the ejection of urine from the urinary bladder through the urethra to the outside of the body.

Key Points

- In infants, elderly individuals, and those with neurological injury, urination may occur as an involuntary reflex.

- Physiologically, micturition involves coordination among the central, autonomic, and somatic nervous systems that stem from different centers of the brain.

- The brain centers that regulate urination include the pontine micturition center, periaqueductal gray, and the cerebral cortex.

- Micturition consists of a storage phase and an avoiding phase. Stretch receptors in the bladder increase their firing rate as the bladder becomes more full. This causes the micturition reflex, and increases urinary urge, and can even cause involuntary urination.

Key Terms

- micturition: Also known as urination, this is the ejection of urine from the urinary bladder through the urethra to the outside of the body.

- urine: A liquid excrement consisting of water, salts, and urea that is made in the kidneys then released through the urethra.

Micturition, also known as urination, is the ejection of urine from the urinary bladder through the urethra to the outside of the body. In healthy humans, the process of urination is under voluntary control. In infants, elderly individuals, and those with neurological injury, urination may occur as an involuntary reflex.

Physiology of Micturition

Physiologically, micturition involves the coordination of the central, autonomic, and somatic nervous systems. The brain centers that regulate urination include the pontine micturition center, the periaqueductal gray, and the cerebral cortex, which cause both involuntary and voluntary control over micturition.

In males, urine is ejected through the penis, and in females through the urethral opening. Due to sexual dimorphism, and the positions where the urethra ends, males and females often use different techniques for urination. Micturition consists of two phases:

- The storage phase: A relaxed bladder in which urine slowly fills the bladder.

- The voiding phase: A contracted bladder that forces the external sphincter open and discharges urine through the urethra.

Location of urethral orifice in females: Location of the external urethral orifice in adult females. between the vestibule and the vaginal orifice.

The muscles controlling micturition are controlled by the autonomic and somatic nervous systems, which open the two sphincters during the voiding phase of micturition. During the storage phase, the internal urethral sphincter is tense and the detrusor muscle is relaxed by sympathetic stimulation. During the voiding phase of micturition, parasympathetic stimulation causes the internal urethral sphincter to relax. The external urethral sphincter (sphincter urethrae) is under somatic control and is consciously relaxed (and thus opened) during micturition.

Many males prefer to urinate standing. In females, the urethra opens straight into the vulva. Because of this, the urine often does not exist at a distance from the body and is therefore seen as harder to control.

The Micturition Reflex

The state of the micturition reflex system is dependent on both a conscious signal from the brain and the firing rate of sensory stretch fibers from the bladder and urethra. At low bladder volumes, the afferent firing of the stretch receptors is low and results in relaxation of the bladder. At high bladder volumes, the afferent firing of the stretch receptors increases and causes a conscious sensation of urinary urge. This urge becomes stronger as the bladder becomes more full.

The micturition reflex causes bladder contraction during voiding, through a neural pathway. This reflex may lead to involuntary micturition in individuals that may not be able to feel the sensation of urinary urge, due to the firing of the stretch receptors themselves.

Waste Management in Other Body Systems

In addition to the kidneys, the liver, skin, and lungs also have important roles in the excretion of waste from the body.

Key Points

The lungs, liver, and skin are the main non- renal system organs involved in waste excretion.

The liver is a vital organ with a wide range of functions, including detoxification, protein synthesis, and the production of the biochemicals necessary for digestion.

The liver converts waste into other substances but does not remove it from the body directly.

The skin has sweat glands that secrete a fluid waste called perspiration, or sweat, which is a pathway for water and ion removal from the body, among other things.

The lungs diffuse gaseous wastes, such as carbon dioxide, from the bloodstream as a normal part of respiration.

Key Terms

- bilirubin: A bile pigment that is a product of the breakdown of the heme portion of hemoglobin, that is processed into bile by the liver.

- urea: A water-soluble organic compound, CO(NH2)2, formed by the metabolism of proteins and excreted in the urine. The liver converts ammonia to urea.

Besides the renal system, many other organs and body systems are directly involved in the excretion of waste products. These other systems are responsible for the elimination of the waste products of the metabolism, as well as other liquid and gaseous wastes, but also provide other critical functions.

The lungs: The lungs are responsible for the removal of gaseous waste from the body.

Similar to renal clearance, these other organs have a clearance rate of their own, and also form a part of total body clearance. The skin, lungs, and liver are the main waste removal organs outside of the non-renal system; however, their ability to remove wastes is generally less than that of the renal system.

Liver Waste Removal

The liver has many vital functions, including a role in digestion, protein synthesis, and nutrient and vitamin storage. The liver also plays an important function in the management of body waste. It acts as a detoxification system for the body, processing and neutralizing drugs and toxins.

The liver is involved in the breakdown and recycling of red blood cells, including the removal of bilirubin from the body by secreting it into the bile, which then functions as a fat emulsifier in the digestive system.

Additionally, the liver is involved in the removal of toxic ammonia from the body by converting it to non-toxic urea, which is then excreted by the kidneys and put into the urine during tubular secretion. While the liver may break down or neutralize waste in a different and safer form for the body, it doesn’t directly remove the waste from the body.

Skin Waste Removal

The skin has sweat glands that secrete a fluid waste called perspiration. Perspiration, or sweat, is a fluid consisting primarily of water, as well as various dissolved solid wastes, that are excreted by the sweat glands. The sweat glands remove a bit of excess water and salts, and also serve the function of cooling the body during thermoregulation.

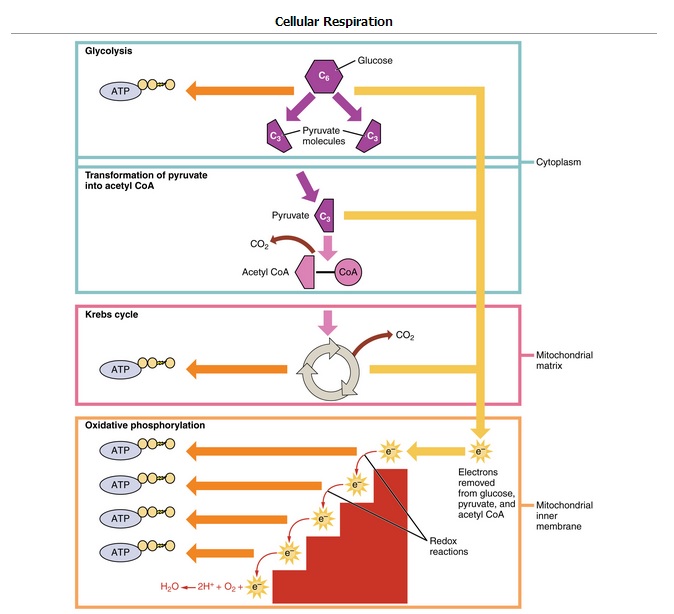

Respiratory Waste Removal

The lungs are responsible for the removal of gaseous waste from the body. Carbon dioxide is a toxic byproduct of cellular respiration. The lungs remove carbon dioxide from the bloodstream during ventilation, exchanging it for oxygen. This function is essentially important for regulating blood pH since blood acidity is directly related to the concentration of carbon dioxide dissolved in carbonic acid in the bloodstream. Excreting more carbon dioxide waste will reduce the acidity of the blood.

References